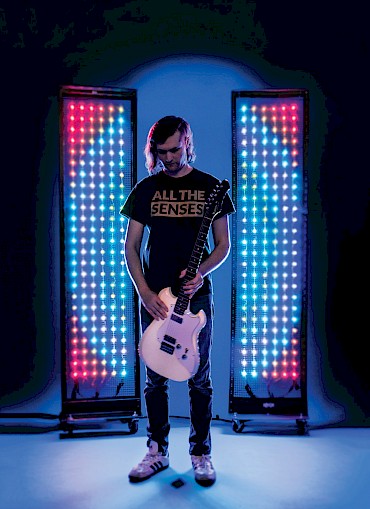

Myles de Bastion is on a mission to amplify our senses and empower us to see sound: Photo by Sam GehrkeMyles de Bastion is a musician and innovator who also happens to be deaf. As a guitarist in Misled Bayonets, his post-rock-flavored live and recording project, de Bastion values the spontaneity of improvised creation.

Myles de Bastion is on a mission to amplify our senses and empower us to see sound: Photo by Sam GehrkeMyles de Bastion is a musician and innovator who also happens to be deaf. As a guitarist in Misled Bayonets, his post-rock-flavored live and recording project, de Bastion values the spontaneity of improvised creation.

“I was frustrated with the challenge of not being able to hear the notes when performing live or jamming with my musician friends,” de Bastion tells. “One day, I had the idea of building a device that would connect to my guitar and transform the audio signal into light and vibration.”

De Bastion tried off-the-shelf lighting fixtures, such as those used by DJs and venues with a “sound active” mode. “To my dismay, all they did was flash random colors whenever there was a loud sound; this hardly gave me enough information to be able to visually see the music. I began researching sound visualization techniques and saw it was possible to visualize the dynamics as well as the frequencies, provided you had a computer that could perform audio analysis. But I still wanted something compact and portable without needing an expensive computer or complex software.”

With a background in computer animation and both hardware and software design, de Bastion put his visual arts and engineering skills to work. While he didn’t have any formal training in product development, he had many talented friends who were willing to teach him. With a small army of volunteers, de Bastion founded CymaSpace, a nonprofit performance venue and technology and arts incubator. With a creative space to build out his ideas, de Bastion began dabbling in cymatic technology, which seeks to make sounds visible, and it wasn’t long before there was a working prototype of the sound-to-light system that became Audiolux One.

The unassuming Audiolux One stomp box has the power translate your instrument’s audio into light: Right photo by Sam GehrkeA first step toward creating a visual sound system, Audiolux One is a plug-and-play stomp box that analyzes seven separate audio frequencies in real-time and maps this musical information to smart LED pixels. It’s capable of taking the sounds from individual instruments and displaying them in light. This means that the visualizations and layout of the LED pixels can be programmed, customizing the colors, luminosity and movement patterns. Thin and flexible, the LED strips and light strings can be installed onto any surface, including inlaid on instruments and gear. The hardware is easily modified through open-source software, allowing for changes in functionality on the built-in knobs and footswitch. Even if you don’t know how to program, you can upload new presets using any computer.

The unassuming Audiolux One stomp box has the power translate your instrument’s audio into light: Right photo by Sam GehrkeA first step toward creating a visual sound system, Audiolux One is a plug-and-play stomp box that analyzes seven separate audio frequencies in real-time and maps this musical information to smart LED pixels. It’s capable of taking the sounds from individual instruments and displaying them in light. This means that the visualizations and layout of the LED pixels can be programmed, customizing the colors, luminosity and movement patterns. Thin and flexible, the LED strips and light strings can be installed onto any surface, including inlaid on instruments and gear. The hardware is easily modified through open-source software, allowing for changes in functionality on the built-in knobs and footswitch. Even if you don’t know how to program, you can upload new presets using any computer.

After people started asking where they could buy the compact, silver stomp box, de Bastion founded Audiolux Devices and began building them to order, while via CymaSpace, he started an outreach arm renting large-scale LED installations for concerts and events, employing technicians for setup and breakdown.

“People want the ‘cool lights’ but we use it as a conversation starter to greater inclusion and accessibility for those with disabilities,” he says. This work not only helps events to be more accessible and inclusive to the deaf and hard of hearing but makes a sensory impact on everyone in attendance. In an effort to share knowledge and lower the barrier of entry to new technology, there’s even a DIY option for ambitious makers wanting to build their own—the open-source code and instructions can be found on GitHub.

With Misled Bayonets, de Bastion approaches songwriting by collaborating with a rotating cast of local musicians and vocalists. Employing a similar tactic, he’s connected with the Portland maker community to create interactive light sculptures such as the Cymatic Star—a sound-reactive LED installation at the Portland Art Museum where museumgoers were actually encouraged to make noise and where softer, higher frequency sounds displayed a light show of cooler tones and louder, lower frequency sounds produced warmer colors. Working with Piano. Push. Play. and Lucid Design, the #SeeingSound LED Piano was created for OMSI, enabling the general public to play a vintage upright that displays different colors and “heat map” patterns depending on which keys are struck.

Top: De Bastion and a full stage of his light sculptures; Bottom: #SeeingSound LED Piano at OMSI, Ear Trumpet Labs mic, and Cymatic Star installation at the Portland Art MuseumOther light-infused gear projects include LED curtains, a see-through kick drum and snare that react to the player’s nuances, a guitar that has a muted technicolor glow strip running the length of its body, a sound-reactive pedalboard, and a dazzling, vintage-style condenser microphone from Ear Trumpet Labs that’s encrusted with LEDs. De Bastion’s work has been featured nationally on Jimmy Kimmel Live with Portland jazz bassist and singer Esperanza Spalding as well as at local happenings like PDX Pop Now!, What The Festival and the Portland Winter Light Festival.

Top: De Bastion and a full stage of his light sculptures; Bottom: #SeeingSound LED Piano at OMSI, Ear Trumpet Labs mic, and Cymatic Star installation at the Portland Art MuseumOther light-infused gear projects include LED curtains, a see-through kick drum and snare that react to the player’s nuances, a guitar that has a muted technicolor glow strip running the length of its body, a sound-reactive pedalboard, and a dazzling, vintage-style condenser microphone from Ear Trumpet Labs that’s encrusted with LEDs. De Bastion’s work has been featured nationally on Jimmy Kimmel Live with Portland jazz bassist and singer Esperanza Spalding as well as at local happenings like PDX Pop Now!, What The Festival and the Portland Winter Light Festival.

Most musicians, bands and orchestras tune their instruments to an international standard (known as A440, or the Stuttgart pitch, at a frequency of 440 Hz). But one begins to wonder, what are the connections between sound and light? What colors erupt during a blistering guitar solo? Does a low, soulful bassline emit blue and feel as soft lit as it sounds? How many kaleidoscopic rainbows can we use to display the tone of music? De Bastion is attempting to answer that question in his next phase of development.

Strum the strings and this guitar’s technicolor coat changes: Photo by Rob Hargreaves“I have experimented with many different approaches to assigning sound information to color,” de Bastion explains. “I like to use a scientific approach such as creating a correlation between the electromagnetic, visible light spectrum and the audible sound frequency spectrum, whereby low frequencies are red and high frequencies are violet with yellows and greens in the middle frequency ranges. My latest prototype, however, takes this even further and I can now correlate a 12-tone musical circle of fifths to 12 different colors that repeat every octave.”

Strum the strings and this guitar’s technicolor coat changes: Photo by Rob Hargreaves“I have experimented with many different approaches to assigning sound information to color,” de Bastion explains. “I like to use a scientific approach such as creating a correlation between the electromagnetic, visible light spectrum and the audible sound frequency spectrum, whereby low frequencies are red and high frequencies are violet with yellows and greens in the middle frequency ranges. My latest prototype, however, takes this even further and I can now correlate a 12-tone musical circle of fifths to 12 different colors that repeat every octave.”

Sound, as it happens, is mathematical. The circle of fifths is like a songwriter’s magic shortcut, expressing the relationship between keys and simplifying chord creation. Mapping this to colored lights allows de Bastion to see what notes are being played by various instruments when improvising, which, more importantly, enables him to turn music into multi-sensorial compositions.

De Bastion’s nonprofit CymaSpace enables inclusivity at events by renting sound-reactive LED installations: Photo by Sam Gehrke“It really feels like a significant breakthrough to be able to make music just by following the colors. I have two different versions of this mapping.” One is based on music theory (the circle of fifths), “where harmonious notes are similar colors, which is a great tool when creating music.” And the other is the chromatic scale, “where adjacent notes are adjacent colors, which is really great for ‘reading’ the music.”

De Bastion’s nonprofit CymaSpace enables inclusivity at events by renting sound-reactive LED installations: Photo by Sam Gehrke“It really feels like a significant breakthrough to be able to make music just by following the colors. I have two different versions of this mapping.” One is based on music theory (the circle of fifths), “where harmonious notes are similar colors, which is a great tool when creating music.” And the other is the chromatic scale, “where adjacent notes are adjacent colors, which is really great for ‘reading’ the music.”

We can all feel music, physically or emotionally—whether it’s the pulse of a bassline, the throbbing heartbeat of a drum, or an emotive piece of music that moves us to joy or tears. CymaSpace projects and Audiolux Devices empower everyone to experience sound in a new way, as a synaesthetic blend of sense and sensation. Sound-reactive lighting and vibro-haptic installations, such as benches or vests that vibrate to the rhythm of the music, create immersive, inclusive environments—a multi-colored, sensory feast that can be enjoyed by anyone and everyone. Through his music, public art and innovation, Myles de Bastion is building inventions that are accessible to all, expanding the deaf community’s experience with live music while bringing together hearing and deaf communities.

“I’m trying to make accessibility cool and exciting through technology—at least that’s the byproduct of efforts to make the world a more friendly and welcoming place for myself and others like me.”