Pok Pok's Andy Ricker buying fresh food at a Thai market: Photo by Dave ReamerYou probably don’t know Andy Ricker, but you might feel like you do. He’s the star of a one-hour Vice documentary, Farang (watch below), which is Thai for foreigner. His Pok Pok restaurants are scattered throughout Portland—there are five in all, not to mention a Michelin-starred one in Brooklyn, N.Y. (Ed. Note: This location closed last September after six years but a new Pok Pok Wing opened in The Cosmopolitan hotel and casino in Las Vegas)—and, thanks to his numerous awards (including two James Beard honors), you’ve maybe even seen him eating and drinking copiously with Anthony Bourdain in Chiang Mai on Parts Unknown, further surveying the Northern Thai food he continues to make and also the country he visits annually for three months at a time.

Pok Pok's Andy Ricker buying fresh food at a Thai market: Photo by Dave ReamerYou probably don’t know Andy Ricker, but you might feel like you do. He’s the star of a one-hour Vice documentary, Farang (watch below), which is Thai for foreigner. His Pok Pok restaurants are scattered throughout Portland—there are five in all, not to mention a Michelin-starred one in Brooklyn, N.Y. (Ed. Note: This location closed last September after six years but a new Pok Pok Wing opened in The Cosmopolitan hotel and casino in Las Vegas)—and, thanks to his numerous awards (including two James Beard honors), you’ve maybe even seen him eating and drinking copiously with Anthony Bourdain in Chiang Mai on Parts Unknown, further surveying the Northern Thai food he continues to make and also the country he visits annually for three months at a time.

But the people who really do know him know that he was once a peripheral player—and a possibly a breath away from being a central player—in Portland’s anything-goes ’90s rock scene.

Ricker grew up in a family that was far more musical than most. For two decades, his father, a fiddler and banjo player, led the Morris dance band at one of California’s Renaissance faires. After his folks split up, Ricker, his mother and his stepfather performed music and told stories with their family friends—sometimes as buskers, sometimes not—and it was his stepdad who expanded his musical world beyond the family’s Beatles and Stones collection, or the old country and British Isles folk sounds, when he took him to a Bob Marley concert shortly before the legend’s untimely death.

Ricker rocking in the '90s while today his renowned Vietnamese fish sauce wings (lead photo above) rock Pok Pok diners' palatesAfter years of backpacking and cooking in kitchens in Australia, New Zealand and England, Ricker decided to call Portland home and almost immediately fell into a flourishing music scene.

Ricker rocking in the '90s while today his renowned Vietnamese fish sauce wings (lead photo above) rock Pok Pok diners' palatesAfter years of backpacking and cooking in kitchens in Australia, New Zealand and England, Ricker decided to call Portland home and almost immediately fell into a flourishing music scene.

“There was some crazy shit going on back then,” Ricker remembers. There were brawls, shootings and run-ins with the cops. “All that stuff that was going on at the Roseland,” he says referencing the club formerly known as Starry Night and its owner Larry Hurwitz who murdered an employee following a John Lee Hooker concert to cover up a counterfeit ticket scam. “That was a dark part of Portland’s rock scene, and you can trace it back to that part of town being the center for the brown heroin trade. Heroin was very prevalent in Portland in the ’90s and you could easily score in that part of town—so Satyricon, Starry Night, Blue Gallery all had some sketchy shit happening.”

But there was plenty of music performed by plenty of people deliberately bent on keeping Portland weird, with Ricker and his friends preferring the scenes at the X-Ray Cafe and Satyricon.

Back then, it wouldn’t be out of the ordinary to drop in at a house party and see Hazel (Pete Krebs’ old band), followed by a heavy metal act, which would then cede the stage to Seattle alt-rockers Harvey Danger.

Ricker, himself, played bass in a number of bands—Moxy Love Crux, 44 Long (listen below), Nancy Hess Band, The Quags—but his favorite experience was providing melodic rhythms in Vehicle, a three-man garage pop band led by an enigmatic and aloof frontman named John Vinzant.

Before meeting Vinzant, Ricker wasn’t particularly fulfilled as a musician, so he put up one of those tear-off ads with his phone number on the bulletin board at 2nd Avenue Records on SW Stark Street. “It probably said something like: ‘Bass for face,’” Ricker drolly recalls.

Soon enough, Vinzant spotted it, gave Ricker a call and handed him a demo. The demo “fried” Ricker’s mind.

“He made these really primitive recordings where he was bouncing tracks between a cassette recorder and a boom box,” Ricker says of his very shy and socially awkward future frontman. “It was ultra lo-fi when that wasn’t a cool thing. It was obvious to me that he was some sort of weird genius.”

Together, they started performing as a duo and played their first gig opening for Elliott Smith at the long-shuttered Umbra Penumbra cafe on SW Ninth Avenue.

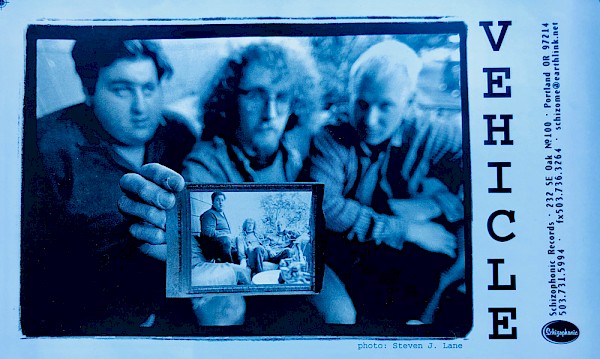

Vehicle press shot of Mike Hughes, John Vinzant and Andy Ricker via Schizophonic Records: Photo by Steven J. LaneIt went well. They played a couple of house parties and then met drummer Mike Hughes, who’d soon supply the trio with two and fours for what eventually became Vehicle. They all moved in together and Vinzant kept churning out songs.

Vehicle press shot of Mike Hughes, John Vinzant and Andy Ricker via Schizophonic Records: Photo by Steven J. LaneIt went well. They played a couple of house parties and then met drummer Mike Hughes, who’d soon supply the trio with two and fours for what eventually became Vehicle. They all moved in together and Vinzant kept churning out songs.

“We all liked The Beatles and The Stones, but John tended toward more obscure musicians like Jandek,” Ricker says. Thanks to SoundCloud (listen below), you can still hear a few of Vehicle’s songs, which have some very Attractions-like hooks—as in Elvis Costello and The—and it’s a very agreeable sound. They even caught the ear of Smith.

“Once, after a show, he complimented John and told him, ‘I really like your songs,’” Ricker says. “They were both such antisocial guys and I remember that conversation as an exchange of weird ‘uhhhs.’”

Vehicle had good chemistry, although they may not have been making much money. (Ricker says the band might collectively earn $150 for a show, which wasn’t enough to live on even back then.) In fact, he jokes that the most money he made in the music industry was painting the West Hills home of Everclear’s Art Alexakis when he took a brief detour as a house painter after growing disillusioned with working the line.

But Ricker was finally playing the kind of bass he wanted to play—“I wanted to play bass as if I was in Sonic Youth”—and they were writing, recording and playing out. Vehicle signed to local label Schizophonic Records. But on the eve of putting out their first record—Can’t Get to Memphis—Vinzant quit. Ricker says he told him that he didn’t want to play music anymore. They played out their final gigs, and after a farewell show at Satyricon, the band dissolved.

At first, Ricker says he was “sad, hurt, confused, resentful and then finally accepted” the breakup, which was complicated by the fact that all three members were sharing a house.

“John disappeared into the basement,” Ricker says. “He knew Mike’s schedule and my schedule and would only come out when we were both gone.”

Ricker, the chef, today: Photo by Dave ReamerEventually, Vinzant moved to New Orleans and then settled in Idaho where Ricker knows, to this day, that Vinzant continues to play music, if only for himself.

Ricker, the chef, today: Photo by Dave ReamerEventually, Vinzant moved to New Orleans and then settled in Idaho where Ricker knows, to this day, that Vinzant continues to play music, if only for himself.

Ricker has continued to play out occasionally, even as he’s expanded Pok Pok’s footprint. But running multiple restaurants—especially one as far away as New York—in addition to spending so much time abroad in Thailand and publishing several best-selling cookbooks, put any dreams of playing music on a regular basis to bed.

When he opened Pok Pok in 2007, Ricker didn’t expect the kind of acclaim that would eventually come his way; but opening his own business and working for himself allowed him to control what he did and how he did it.

It turned out to be a pretty good fallback plan.