Like father, like daughter: Erik and Harbor ClampittBefore we were parents, I used to tease my partner, David, that once we had a baby, he’d have to quit all his bands. It’s an old joke about musicians and one I enjoyed heckling his bandmates with almost as much as him. But now that we are parents, it constantly surprises me how many people maintain this stigma.

Like father, like daughter: Erik and Harbor ClampittBefore we were parents, I used to tease my partner, David, that once we had a baby, he’d have to quit all his bands. It’s an old joke about musicians and one I enjoyed heckling his bandmates with almost as much as him. But now that we are parents, it constantly surprises me how many people maintain this stigma.

The comments come from all over.

“I can’t imagine [if my husband] were still in a band,” one friend said to me, holding her 1 year old close. “He was just gone so much.”

“David’s so busy!” I hear from family. “I don’t know how you do it.”

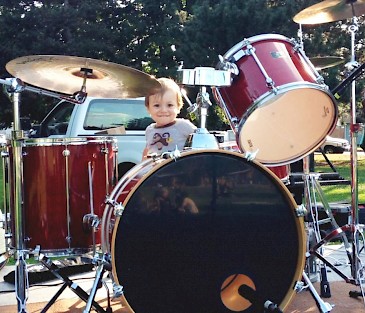

The budding drummer Isaac at a summertime School of Rock show. Photo by Annette JohnsonLike any profession or interest, being a musician requires time. David Coniglio rarely has an entire day free, be it teaching lessons, practice, studio time, a gig or even just moving gear. He is the assistant music director at the Portland School of Rock, an instructor at Revival Drum Shop, and involved in several bands, including 1939 Ensemble and Humours. Nights, especially weekends, fill up fast. We’re lucky that he doesn’t go on the road a lot these days.

The budding drummer Isaac at a summertime School of Rock show. Photo by Annette JohnsonLike any profession or interest, being a musician requires time. David Coniglio rarely has an entire day free, be it teaching lessons, practice, studio time, a gig or even just moving gear. He is the assistant music director at the Portland School of Rock, an instructor at Revival Drum Shop, and involved in several bands, including 1939 Ensemble and Humours. Nights, especially weekends, fill up fast. We’re lucky that he doesn’t go on the road a lot these days.

Making our situation work requires being able to accept a nontraditional schedule. There are times I lament solo bedtime duties, and many mornings both of us want to sleep in. As a freelance writer, my schedule is also not steady. While a lot of parents require a strict routine, we follow more of a loose daily pattern.

On the flipside, there is an inherent flexibility to David’s schedule that adds an aspect of freedom to our lives we would be loath to give up. In comparison to other professions, we feel fortunate; so many careers require a parent to be gone so much more.

Part of the stigma might come from touring. Being away is a constant struggle for entertainers.

Local musicians Tony Furtado and Stephanie Schneiderman have a son who is 2. Both are singer-songwriters as well as recording and performing artists. Schneiderman also teaches guitar, piano and songwriting out of their house. In this way, she is able to stay home more often, but Furtado is gone about 12 days a month, he says, depending on the time of the year.

“I rely so heavily on touring for income that it’s a very delicate balance between being away from home and touring enough to make the money I need,” Furtado explains. “Right now, the time I’m away is really harder on me and Stephanie than it is on our son.”

The Unwound Fang Family: Aaron Beam, Niko and Sara Lund. Photo by James RexroadAaron Beam, father of a 5-year-old son and a guitar player who dabbles in electronic music on top of being the bassist and a singer in Red Fang, can empathize. Red Fang tours frequently, often for weeks at a time.

The Unwound Fang Family: Aaron Beam, Niko and Sara Lund. Photo by James RexroadAaron Beam, father of a 5-year-old son and a guitar player who dabbles in electronic music on top of being the bassist and a singer in Red Fang, can empathize. Red Fang tours frequently, often for weeks at a time.

“It’s quite difficult,” he says, “and requires constant maintenance of the relationship so nobody gets angry or resentful. This actually mostly takes effort to hold yourself in check. And discussions about how to share the work of childrearing.”

Like Furtado and Schneiderman, Beam is just one half of a musical power duo: His partner, Sara Lund, is a prominent drummer, perhaps best known for playing in Unwound.

“You have to be able to accept the idea that you might just have to do more sometimes than your partner,” he emphasizes. “And likewise, the person who is away more just has to accept that your kid is probably going to have a preference for the parent who is around more.”

“When I’m on tour, I do my best to make sure there are no off days,” Furtado says. “Off days kill me! It’s hard enough to be away, but to be away and not have it be for any reason—ugh!”

“It also takes being as ‘present’ as possible when you are actually hanging out with your kid,” Beam adds.

Furtado agrees. “When I’m home, I do my best to be right there as much as I can for Stephanie and Liam.”

One of my uncles is a pilot. These days, he flies commercial flights and can be gone for days at a time. Before he had seniority, the stretches were longer. A couple of my brothers-in-law are in sales. Travelling is a part of their job, and even when they are home, work hours exceed the standard 9 to 5. Some other family members work long hours in television. Taping can require double overtime. For years, David and I worked full-time in the service industry on top of other creative pursuits. In comparison, David’s current schedule is quite manageable.

“I haven’t been on a tour in years now, and From Ashes Rise usually flies in to do one-off shows these days, although we’re currently taking time off to write a record,” guitarist and vocalist Brad Boatright says. Touring and recording for more than 20 years, he’s now working full-time as a mastering engineer at his own studio, Audiosiege. His son, Wesley, is almost 2.

“This is an ideal situation that I’ve made work and planned for a long time,” he explains.

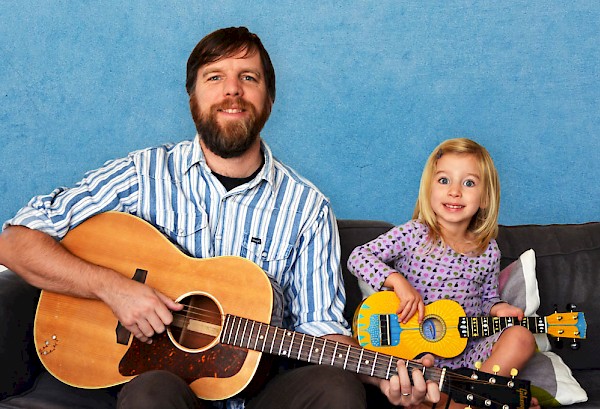

A dad can dream she’ll grow up to play pedal steel: Clampitt and Harbor. Painting by Adam BurkeEven without being on the road, the balance of creative careers can be stressful. Erik Clampitt plays guitar and pedal steel with Hook & Anchor, Power of County and with Cristina Cano’s Siren & the Sea. On average, he has three to four shows a month in the Portland area or even at the coast.

A dad can dream she’ll grow up to play pedal steel: Clampitt and Harbor. Painting by Adam BurkeEven without being on the road, the balance of creative careers can be stressful. Erik Clampitt plays guitar and pedal steel with Hook & Anchor, Power of County and with Cristina Cano’s Siren & the Sea. On average, he has three to four shows a month in the Portland area or even at the coast.

“The most important key to this equation is my wife, who is a realtor with a fairly flexible schedule and very understanding of my schedule,” Clampitt says.

“I don’t think I could handle being away for months—or even weeks—at a time these days,” Boatright admits. He feels his workload is “about average,” between putting in 40 hours a week at Audiosiege and extra hours for band practice.

“Hell, I couldn’t imagine working a ‘normal’ job either, though,” he says. “Fortunately, I get to live vicariously through the bands I work with.”

Working from home also helps Clampitt. He and his wife host a nanny share with three other families, allowing him to balance “regular hours” as a graphic designer and time with his 3-year-old daughter, Harbor.

“I get to pop upstairs and have lunch or play in the backyard with her, which is great,” Clampitt says. “Her bedtime is early enough that often I leave for rehearsals or shows after she goes to bed.”

“I’m trying to keep a balance between being there for [my son] during this important time as well as creating space for me to write, teach, gig and practice,” Schneiderman says. An afternoon nanny who comes to the house while she teaches in her basement studio is a part of this balance.

“And once he’s asleep or napping, I try to use that time to work on music,” she adds.

Even with being on the road, Furtado feels he has similar hours to someone who might have a more common, full-time job. He doesn’t have a day job when he’s off the road, so when he’s home, he’s mostly around the house.

“It’s hard to quantify hours rehearsing and performing versus a typical 40-hour-a-week job,” Clampitt says. “But as bands get busier, that number goes up.”

Starting ‘em young: Lund and an 18-month-old Niko. Photo by Megan HolmesBeam says he gets “pretty sucked into most jobs—regardless of how menial they may be.” No matter what, though, Beam says he has always invested a lot of his time into music-related projects.

Starting ‘em young: Lund and an 18-month-old Niko. Photo by Megan HolmesBeam says he gets “pretty sucked into most jobs—regardless of how menial they may be.” No matter what, though, Beam says he has always invested a lot of his time into music-related projects.

“I am lucky enough to play in a band that can afford to pay people to do a lot of [the promotional work], so I would say, as of today, I spend much less time dedicated to being a musician compared to my other [previous] careers—at least on the business side. It’s hard to say on the creative side because that part is constant,” Beam explains. “Whether I have a day job or not, I can’t really quantify it.”

David tells his younger students interested in following the path of music as a profession that it’s an act of love. You can’t expect fortune or glory: The urge has to come from somewhere deeper. It has to be a part of you and a part of who you want to be. In other words, it’s a lifestyle choice. I feel the same way about my own career and goals as a wordsmith. Having a child hasn’t changed us in those ways, but it does mean we have to be mutually supportive of each other and communicate well.

Both Beam and Clampitt point out how useful it is to share a calendar. It sounds simple, but as Beams says, “That actually helps a lot.”

David and I are fortunate to be at a point in our lives where we can survive by doing work that, for the most part, speaks to us. We’re doubly lucky to be able to spend so much time with our 2-and-a-half-year-old, Isaac.

“I spent 13 years at an in-house, corporate art department working 40 hours a week, being held to someone else’s schedule, making for stretches of downtime,” Clampitt says. “I now feel like I have much more control over my schedule.”

Schneiderman is happy with her situation too.

Schneiderman is happy with her situation too.

“It’s actually been a good schedule for us,” she says, admitting she used to tour more but has cut back to stay at home. “It’s allowed me much more time with my son.”

“Being an artist, getting to live your life as you want is awesome, and being able to share that experience with your kid is the greatest,” David says. “At the same time, you go to the park and see other families with a more 9 to 5 schedule, and it can make you feel a little alienated for not having a set routine.

“It’s just a more radical way of living,” he sums up.

The other night, David’s practice was called off. Generally on band nights, he goes straight from teaching to the rehearsal space. Instead, he was grateful to come home. But Isaac was having a tough time. Everything was a struggle—dinner, the bath, pajamas. There was a lot of crying.

“Glad you got the night off?” I teased.

He smiled. Rolled his eyes. “Yeah,” he said. “I am.”