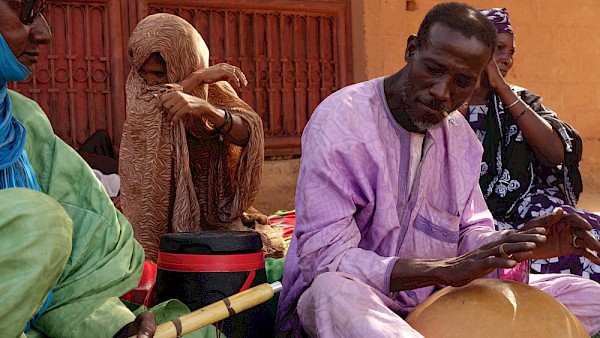

Oumou Diabate and Christopher Kirkley making a field recording in Bamako, Mali: Photo by Maciek Pozoga

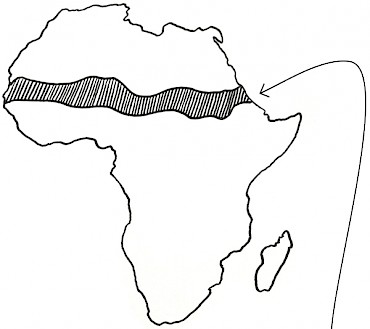

Oumou Diabate and Christopher Kirkley making a field recording in Bamako, Mali: Photo by Maciek Pozoga The Sahel is a semi-arid band of land that runs across Africa separating the Sahara desert and the tropical Sudanian SavannaIt’s been a decade since Christopher Kirkley first landed in the region of northern Africa known as the Sahel, a semi-arid band of land that runs across the continent separating the Sahara desert and the tropical Sudanian Savanna. A self-described “amateur ethnomusicologist,” he deliberately sought out an area virtually untapped by English-speaking Westerners, hoping to immerse himself in a musical lexicon without the possibility of cultural biases clouding his judgement.

The Sahel is a semi-arid band of land that runs across Africa separating the Sahara desert and the tropical Sudanian SavannaIt’s been a decade since Christopher Kirkley first landed in the region of northern Africa known as the Sahel, a semi-arid band of land that runs across the continent separating the Sahara desert and the tropical Sudanian Savanna. A self-described “amateur ethnomusicologist,” he deliberately sought out an area virtually untapped by English-speaking Westerners, hoping to immerse himself in a musical lexicon without the possibility of cultural biases clouding his judgement.

What he found there was an artist community empowered by the recent arrival of cell phones. But without actual reliable phone service, the devices proved better used for sharing music using SIM cards, Bluetooth and hard drives. Marketplaces vibrated with music—particularly electronic and hip-hop—played through computer speakers and available for download via flash drives.

Literally 'Music from Saharan Cellphones,' which was also the title of one of Sahel Sounds' first releases—"a compilation of music collected from memory cards of cellular phones in the Saharan desert"It was in this setting that Kirkley’s Portland-based Sahel Sounds was born, initially as a blog to share his field discoveries and eventually expanding into a label, film production house and artist collective. One of the label’s first releases was an aptly titled compilation, Music from Saharan Cellphones, and Kirkley’s focus on equitable relationships with musicians informed one of the larger tasks related to its release: tracking down the artists for the appropriate permissions and to establish contact for distributing payment. Sixty percent of proceeds from the first volume went directly to the artists.

Literally 'Music from Saharan Cellphones,' which was also the title of one of Sahel Sounds' first releases—"a compilation of music collected from memory cards of cellular phones in the Saharan desert"It was in this setting that Kirkley’s Portland-based Sahel Sounds was born, initially as a blog to share his field discoveries and eventually expanding into a label, film production house and artist collective. One of the label’s first releases was an aptly titled compilation, Music from Saharan Cellphones, and Kirkley’s focus on equitable relationships with musicians informed one of the larger tasks related to its release: tracking down the artists for the appropriate permissions and to establish contact for distributing payment. Sixty percent of proceeds from the first volume went directly to the artists.

A lot has changed over the last 10 years, mostly for the better, Kirkley says. For starters, the ways in which he is able to communicate with artists are much better; Kirkley is especially fond of WhatsApp “because we can send vocal messages back and forth, send audio for identification, solicit new songs, and get videos and promotional material.” In fact, Kirkley says, “Recently we booked an entire European tour with an artist from Mauritania [named Ahmedou Ahmed Lowla] off the strength of a video he sent to me, and that I shared on Instagram—which caught the attention of booking agents and promoters.”

But with increased exposure comes increased attention, including from the government. Kirkley cites visas for touring artists as “a constant thorn in [the label’s] side.” And increased concerns over radicalized groups have brought about a heightened military presence.

A participant at the Shiriken Festival, which celebrates Tuareg culture, dance and music, in Akoubounou, Niger; camels are integral to the traditional Tuareg way of life and the fest features camel races, desert blues music and even camel dancing, where riders make their camels step to a drumbeat: Photo by Christopher Kirkley“When I started working in the Sahel, there wasn’t much attention on this part of the world in the West. Today it’s a lot more visible as there’s a threat of terrorism, and the United States military has increased its presence. I feel like our work is under more scrutiny than it once was,” Kirkley describes. “For a while, I was on a government watch list because of my travels to the Sahel, and got shaken down every time I passed through TSA.”

A participant at the Shiriken Festival, which celebrates Tuareg culture, dance and music, in Akoubounou, Niger; camels are integral to the traditional Tuareg way of life and the fest features camel races, desert blues music and even camel dancing, where riders make their camels step to a drumbeat: Photo by Christopher Kirkley“When I started working in the Sahel, there wasn’t much attention on this part of the world in the West. Today it’s a lot more visible as there’s a threat of terrorism, and the United States military has increased its presence. I feel like our work is under more scrutiny than it once was,” Kirkley describes. “For a while, I was on a government watch list because of my travels to the Sahel, and got shaken down every time I passed through TSA.”

On the Sahel side, the occupation of northern Mali by extremists actually resulted in a cell phone music ban in 2012. Frustrating ordeals, no doubt, but Kirkley sees the extra effort as a relatively small cost for the greater good: “I think it’s more important than ever to highlight voices and perspectives from the Sahel that go against this ‘terrorism’ narrative.”

In that spirit, Sahel Sounds maintains relationships with virtually every artist on the roster, in varying degrees. Sahel Sounds “tends to be a bit more involved than a typical label, because of the needs of the artists,” Kirkley explains. “It’s very rarely just a release. For the majority we are their representative to the music business, so it extends into managing careers, booking tours, making films, negotiating contracts with other labels, licensing deals—but also looking for new projects, securing funds for artistic opportunities, and sometimes just advancing money in crises.”

And while Kirkley is more than willing to help out financially in these situations, he works hard to dispel any assumptions that he’s a wealthy American simply handing out money and perpetuating appropriation. In his early days in the region, Kirkley even occasionally brought out a guitar to jam along, but he soon put it away in favor of listening—even when listening meant waiting for someone to pull out a cell phone instead of an instrument, initially an off-putting experience for Kirkley’s Western mores.

A group of musicians—including Mdou Moctar’s rhythm guitarist Ahmoudou Madassane with the red guitar—jamming in Agadez, Niger: Photo by Christopher KirkleyAccountability is also an issue. Participating as a musician, producer or recordist, “it’s so easy to... put your own taste and aesthetic all over it,” he says. Kirkley has previously noted that ethnomusicologists 60 years ago weren’t held to the same standards that today’s are, telling Pitchfork in 2016: “When they were doing field recordings in the ’50s, the artists on those recordings never saw those records. But people today are going to see them: I can record a musician and we can immediately friend each other on Facebook. They see pictures of where I live. Over the past few years, we’ve bridged this chasm and [the cultures] don’t seem so far away anymore.”

A group of musicians—including Mdou Moctar’s rhythm guitarist Ahmoudou Madassane with the red guitar—jamming in Agadez, Niger: Photo by Christopher KirkleyAccountability is also an issue. Participating as a musician, producer or recordist, “it’s so easy to... put your own taste and aesthetic all over it,” he says. Kirkley has previously noted that ethnomusicologists 60 years ago weren’t held to the same standards that today’s are, telling Pitchfork in 2016: “When they were doing field recordings in the ’50s, the artists on those recordings never saw those records. But people today are going to see them: I can record a musician and we can immediately friend each other on Facebook. They see pictures of where I live. Over the past few years, we’ve bridged this chasm and [the cultures] don’t seem so far away anymore.”

Kirkley has grown more comfortable with his many roles in the process. “At the inception of this work, I really tried to hide my presence from the recordings, but I embrace it now—and just try to make it evident and transparent. As much as you can minimize your work, when there’s mediation in any art, that art becomes a collaboration. I just tread carefully, be respectful, and try my best to end up with something that we can all be happy about.”

And Sahel Sounds has a lot to celebrate these days. In addition to a roster boasting over 20 artists, the outfit has released two full-length feature films, including a reimagining of Purple Rain—called Akounak Tedalat Taha Tazoughai, or Rain the Color of Blue with a Little Red in It because there is no word for purple in Tamajeq—featuring original work by Tuareg musician Mdou Moctar (watch the trailer below), and an adaptation of Titanic, with a truck traversing the Sahara standing in for the doomed ship crossing the Atlantic, is forthcoming. And the label continues to expand in new and exciting ways.

Mohamed Yaseen playing traditional takamba music in his neighborhood in Niamey, Niger: Photo by Markus Milcke“We’re in a growing phase right now,” Kirkley says. “I’ve brought on a lot more people and outsourced other parts of the business so it can be self-sustainable—with the music and label part providing our main income.”

Mohamed Yaseen playing traditional takamba music in his neighborhood in Niamey, Niger: Photo by Markus Milcke“We’re in a growing phase right now,” Kirkley says. “I’ve brought on a lot more people and outsourced other parts of the business so it can be self-sustainable—with the music and label part providing our main income.”

“When I talk about Sahel Sounds as an organization or collective, it’s in the sense that I like all of our artists to know that they’ll be part of a team, and that extends beyond their records and into other creative pursuits. I’d like to reach a place where our projects with artists and musicians nurture and extend that creativity, where we can secure funding and resources for our artists, and allow a space of creation, through residencies or musical equipment.”

As Kirkley’s role becomes more nuanced and Sahel Sounds continues to fortify its relationships both with its musicians and audience, reaching that goal likely isn’t an issue. Rapidly changing technology and politics will almost certainly yield some surprising turns on the journey, though.