Mic Crenshaw at PDX Pop Now! 2015—click to see a whole gallery of photos from the festival by Henry NovakPop music is the meat at the barbecue joint, says hip-hop emcee and poet Mic Crenshaw—it’ll fill you up with empty calories “and weigh you down, and slow you down.”

Mic Crenshaw at PDX Pop Now! 2015—click to see a whole gallery of photos from the festival by Henry NovakPop music is the meat at the barbecue joint, says hip-hop emcee and poet Mic Crenshaw—it’ll fill you up with empty calories “and weigh you down, and slow you down.”

Political music, the sound of the struggle, Crenshaw says, “is like one of the sides—it’s something extra that you get.”

This story is about the sides: the greens, cheesy macaroni, cornbread, red beans and rice.

On the heels of a national election that threw down the gauntlet, Portland artists are responding with music that’s more ecstatically political than anything we’ve ever heard. Long at the forefront of local protests, PDX musicians say they’re increasingly putting adrenaline on paper, taking the bullhorn to the studio.

The trend reverberates across scenes and cultures.

“You stand for something or fall for anything,” says rapper Cool Nutz (birth name Terrance Scott), who has a new, hyperconscious album, Pig Ears & Chitlins, due out on April 14. Scott says the release “relates to a number of things from gentrification, race issues, and just overall issues that affect people of the minority and color.”

“I need something to do right now, I feel so helpless,” says Leona, bassist and vocalist in punk trio Mr. Wrong, who calls the election a “punch to the face.” “Making music about what’s going on is all I want to do,” she says. “It helps me and then I can hope that it will effect some kind of greater change.”

“It would be hard not to write political music in this climate,” says singer-songwriter Sean Flinn, who released a gorgeously spare political tune called “Shadow Boxing” in the days following the election. “I think that we’re going to see a lot more of it,” as activism, civic engagement, social commentary and political music are all “on the rise,” he says.

Cool Nutz at the Portland Black Music Festival at the Mission Theater in September 2016—click to see more photos by Tojo AndrianarivoLocal hip-hop emcees will be near the fore of this movement. On Cool Nutz’ Pig Ears & Chitlins, Crenshaw goes full warrior in a political-poetic interlude:

Cool Nutz at the Portland Black Music Festival at the Mission Theater in September 2016—click to see more photos by Tojo AndrianarivoLocal hip-hop emcees will be near the fore of this movement. On Cool Nutz’ Pig Ears & Chitlins, Crenshaw goes full warrior in a political-poetic interlude:

“Your ideas of reality have you confused / Let’s be clear / You fear my aggression because you attack my complexion / But what you call riot is insurrection / What you call violence is self-defense and protection / Since prior to this society’s inception / I haven’t existed an instant, a second / Without being against persistent and consistent oppression.”

“Black Music,” a breakout track on the record, features emotional turns by Cool Nutz, Crenshaw, Mic Capes and a searing, shimmering chorus by April Cason-Etuk: “We gonna keep on making black music / like black oil they just wanna use it / But we can’t stop doing what we doing / We are the beginning, it’s proven.”

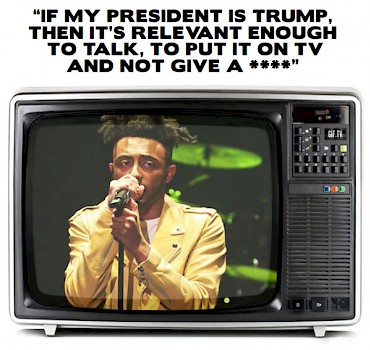

A week after the election, Aminé added an anti-Trump verse to the end of his “Caroline” performance on Jimmy Fallon’s 'The Tonight Show'—watch belowPortland rapper Aminé gave the nation his own moment of electrifying political music on Jimmy Fallon’s The Tonight Show in November. His single “Caroline,” with more than 300 million streams on various platforms, included a new verse: “9/11, a day that we’re never forgettin’ / 11/9, a day that we all regrettin’ / If my president is Trump, then it’s relevant enough / To talk, put it on TV and not give a [****]”—watch the video below.

A week after the election, Aminé added an anti-Trump verse to the end of his “Caroline” performance on Jimmy Fallon’s 'The Tonight Show'—watch belowPortland rapper Aminé gave the nation his own moment of electrifying political music on Jimmy Fallon’s The Tonight Show in November. His single “Caroline,” with more than 300 million streams on various platforms, included a new verse: “9/11, a day that we’re never forgettin’ / 11/9, a day that we all regrettin’ / If my president is Trump, then it’s relevant enough / To talk, put it on TV and not give a [****]”—watch the video below.

Then in the first month of 2017, another PDX hip-hop emcee, Foday, released a blistering anti-Trump anthem. The video for “Never” includes footage of local post-election rallies and is followed by the spoken-word poem “Thoughts on our President”—watch at the end of this article.

Emcees Mic Capes, Glenn Waco (a leader at Don’t Shoot Portland rallies) and Rasheed Jamal formed The Resistance in 2011—long before the post-Trump Portland’s Resistance protest movement hit local headlines.

“Everybody feels equally offended right now, or at least we think we do,” Jamal says. “But black people are sitting back like, ‘Word?’ It’s like duh, muthafucka, I been feeling like this.”

T-Shirts and Politicizing Anthems

Mr. Wrong’s Leona and Moff say people at the post-election rallies downtown wore the band’s T-shirts because Donald Trump is the “epitome” of Mr. Wrong.

In songs like “Do You Have a Job For a Girl Like Me?,” the trio write edgy content that reflects their work in the Amplification Series, a concert series to benefit survivors of sexual assault they say “are being silenced by legal retaliation.”

“I’m not really worried about alienating people at this point, because everyone’s pissed,” Leona says. The band’s next album will be more political than ever. “The people who aren’t alienated, I want them to feel uncomfortable.”

Singer-songwriter Sean Flinn’s music is less noisy, but no less political. He played “Shadow Boxing” (listen below) for a thousand at a post-election Revolution Hall “brainstorming” event, What Now?

“I had a dream last night / I was feeling free / But I woke to a broken democracy,” Flinn sings in the song. “All that milk and honey / for the oligarchy / In a land of growing poverty / Watch those talking heads / try and spin it right / It’s a sport they play / between the left and the right / They’re just shadow boxing in the night.”

The Pitfalls of Political Music

Politically charged music is nothing new for Portland artists like Team Dresch, Sleater-Kinney, Tragedy and many others. The toughest part, veteran artists say, isn’t making music with a message—it’s creating good music with a message.

“Any time you tell your opinion in your art, you’re going to risk alienating people,” says Hutch Harris, lead songwriter and vocalist of The Thermals. “Another risk is that if you’re too specific about what you’re talking about, the songs are going to be too dated and they’re going to go stale.”

Crenshaw says people he knows have openly questioned his commitment to making conscious rap in the past. “I feel like they thought, ‘If this dude was smart he would make music about parties and bitches and getting money, because he obviously has the skills, but he just wants to focus on all that political shit.’”

Yet staying true to his message offered Crenshaw the opportunity to work with Dead Prez, curate a hip-hop rally for Jill Stein and the Green Party, and travel to play in Africa four years in a row.

On Halloween weekend at Mississippi Pizza, musician and activist Darka Dusty organized Death of Democracy?, “a spirit-filled night of protest and political songs, humor and a public soapbox,” where Americana singer-songwriter Amanda Richards (pictured) offered the crowd her “motivational country satire,” imploring them to “Grab Life by the Pussy”—a song written in honor of “an orange leather fella in a yellow toupée.” Click to see more photos by Miri Stebivka and hear the song.Flinn and other folk-oriented artists like Alexa Wiley, Dragging an Ox through Water, Amanda Richards, Michael Dean Damron and others carry on the tradition of artists like Woody Guthrie, who once made political music in Portland and, in 1948, penned a piercing protest ballad about the Vanport flood.

On Halloween weekend at Mississippi Pizza, musician and activist Darka Dusty organized Death of Democracy?, “a spirit-filled night of protest and political songs, humor and a public soapbox,” where Americana singer-songwriter Amanda Richards (pictured) offered the crowd her “motivational country satire,” imploring them to “Grab Life by the Pussy”—a song written in honor of “an orange leather fella in a yellow toupée.” Click to see more photos by Miri Stebivka and hear the song.Flinn and other folk-oriented artists like Alexa Wiley, Dragging an Ox through Water, Amanda Richards, Michael Dean Damron and others carry on the tradition of artists like Woody Guthrie, who once made political music in Portland and, in 1948, penned a piercing protest ballad about the Vanport flood.

“Sometimes when you’re feeling really strongly about something, a song just kind of writes itself,” Flinn says. Then, the creative process brings new questions. “Do you go for a full record of that? It’s just one of the challenges that you face when you’re trying to create an aesthetic around a record,” he says.

“Fall in Line”

The music industry is not welcoming to in-your-face content, Harris warns. “The industry never wants you to do anything political,” he explains. “The industry wants everyone to fall in line.”

Then he chuckles, reflecting on the irony that The Thermals’ most successful recording, its 2006 Sub Pop release, The Body, The Blood, The Machine, is its most political. “Maybe it was a risk, but it paid off,” Harris says. “Part of it was because it was political and part of it was because the songs are good, and it just came out at the right time.”

One way around the problem, Jamal says, is to intersperse political tracks with bangers, as Tupac did. “You miss out on a lot of opportunities when you don’t make pop music,” he says. “There’s a certain type of mold, there’s a certain formula. At the end of the day, it’s a white-owned industry,” Jamal says.

Simon Tam (left) and his Asian-American dance rock band The Slants have been in a trademark battle, one that made it all the way to the Supreme Court, for more than seven years: Photo by Sarah GiffrowSimon Tam of The Slants can attest to that. “The music industry itself can still be very prejudiced and often relies on outdated racial and sexist stereotypes,” Tam describes. “For example, once we were offered a major record label deal—as long as we replaced our lead singer with someone who was white because they said: ‘Asian doesn’t sell.’”

Simon Tam (left) and his Asian-American dance rock band The Slants have been in a trademark battle, one that made it all the way to the Supreme Court, for more than seven years: Photo by Sarah GiffrowSimon Tam of The Slants can attest to that. “The music industry itself can still be very prejudiced and often relies on outdated racial and sexist stereotypes,” Tam describes. “For example, once we were offered a major record label deal—as long as we replaced our lead singer with someone who was white because they said: ‘Asian doesn’t sell.’”

The Slants’ decision to choose a provocative name wasn’t intended to be political, Tam says in his TEDx talk “Losing the Line Between Art and Activism.” It was “a reference to our perspective in life, as people of color, as geeks and as musicians,” he explains. According to Tam, their trademark application was the only one of 800 related to the word to be rejected by the United States Patent and Trademark Office, citing that the name is a disparaging term. The case is now nearing its conclusion in the Supreme Court after a January hearing. The publicity hasn’t hurt the band’s name recognition, and they haven’t shied away from putting activism into their music either, in songs like “Anthem.”

Click to read more about Rasheed Jamal and life as a black musician in Portland: Photo by Sam GehrkeEchoing Tam, Jamal emphasizes that it’s important not to “box in” artists as “political” or “protest” simply because their work reflects the experience of a community or group that’s marginalized. “If my music comes off as political because I like to educate and speak my own truth then so be it,” Jamal says. “But, that’s not necessarily the aim or purpose. To be seen as political is one thing, but to be boxed in as an artist is much different.”

Click to read more about Rasheed Jamal and life as a black musician in Portland: Photo by Sam GehrkeEchoing Tam, Jamal emphasizes that it’s important not to “box in” artists as “political” or “protest” simply because their work reflects the experience of a community or group that’s marginalized. “If my music comes off as political because I like to educate and speak my own truth then so be it,” Jamal says. “But, that’s not necessarily the aim or purpose. To be seen as political is one thing, but to be boxed in as an artist is much different.”

If there’s money to be made reaping the hurricane, the music industry isn’t blind to what’s blowin’ in the wind. Mama C, an artist and elder Black Panther, told Crenshaw this moment feels like 1968 all over again. One way of understanding this moment might be to bust out the old vinyl: Nina, Bob, Bob, The Beatles, Aretha, Otis, James, Janis, Sly.

Casey Jarman, half of local label Party Damage Records, says the whole music community needs to make inclusive choices. “We need to raise up people who are investing in diversity and tolerance—people who are working for positive change—in our community, and reject those who are spouting the kind of values that are apparently now accepted as mainstream political ideology,” he says.

Immigrants and Logarithms

A key difference between the 1960s and today is the percentage of immigrants in the U.S.: under 5 percent in 1965; now about 14 percent, according to the Pew Research Center.

Combined with our new president’s wall-building, anti-immigrant politics, this demographic reality could amplify the sound of artists like Aminé, the son of Ethiopian immigrants, or Asian American artists like The Slants, or Latino artists like Máscaras or Tiburones.

“All music is political,” Tam notes. Nowhere is this more true than in the live concert experience, when the energy of people coming together transcends the individualizing effects of four walls, of social media.

So if you go to a local music venue this winter, you might just hear some amazing, heartbreakingly political music.

“We’re just about to begin working on our new album, and this election is fuel for the fire,” says Lucas Warford of Three For Silver, who headlined a pre-election show called Death of Democracy? produced by Darka Dusty at Mississippi Pizza and often perform at May Day events. “Everyone is feeling galvanized.”

Exciting, but also “Scary”

Lucas Warford of Three For Silver performing at Mississippi Pizza for the Death of Democracy? event organized by Darka Dusty—click to see more photos by Miri Stebivka“One of the things that I think is really important right now is expanding these bubbles and finding the intersectionality of all these struggles,” Leona says. “Because it’s scary. It’s really scary.”

Lucas Warford of Three For Silver performing at Mississippi Pizza for the Death of Democracy? event organized by Darka Dusty—click to see more photos by Miri Stebivka“One of the things that I think is really important right now is expanding these bubbles and finding the intersectionality of all these struggles,” Leona says. “Because it’s scary. It’s really scary.”

For Warford, the hard part is to keep hands open—not clenched. “It’s very challenging to stand in opposition to [injustice] and not be infected by the same badness that caused it in the first place,” Warford warns. “Not becoming as fanatical as the thing that you’re trying to oppose.”

Crenshaw, for one, sees potential in the growing movement. “There’s an opportunity right now for people who might not have been pushing a message to be in solidarity with people who put the message in the fore,” he says.

Whatever happens, Stumptown’s artists and listeners are certain to be blessed by powerful new protest music—both from those who have been fighting the power and myriad newcomers.

So have a seat, or grab some to go—Portland’s 2017 aural dinner menu now features plenty of spicy and succulent dishes, heating both bellies and boulevards.