A scene from Northwest String Summit at Horning's Hideout in July 2019—click to see more photos by Blake Sourisseau“What times are these? When a conversation about trees is almost a crime?” wrote German playwright and songwriter Bertolt Brecht in his 1939 poem To Future Generations. By that point, Brecht had lived through the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic, the Great Depression and World War I, and while Hitler’s reign grew with World War II on the horizon, this piece appeared with the subtitle: “A Poem for Dark Times.” It makes sense that a Marxist-German artist living in exile of fascism would consider a conversation about trees as political because it implied a silence about so many atrocities.

A scene from Northwest String Summit at Horning's Hideout in July 2019—click to see more photos by Blake Sourisseau“What times are these? When a conversation about trees is almost a crime?” wrote German playwright and songwriter Bertolt Brecht in his 1939 poem To Future Generations. By that point, Brecht had lived through the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic, the Great Depression and World War I, and while Hitler’s reign grew with World War II on the horizon, this piece appeared with the subtitle: “A Poem for Dark Times.” It makes sense that a Marxist-German artist living in exile of fascism would consider a conversation about trees as political because it implied a silence about so many atrocities.

I bring it up now, in the midst of the spread of Covid-19 and the concurrent economic collapse, because it’s times like these when it seems music and poetry and conversations about trees become luxuries.

As scratchboard artist and poster designer Gary Houston notes, “Those of us who work in the field we do—entertainment, or on the periphery of it—are becoming aware that we are involved in a disposable area of life. I don’t mean that the arts aren’t important, because they are, but when toilet paper is a top priority, creativity seems to have taken a back seat.”

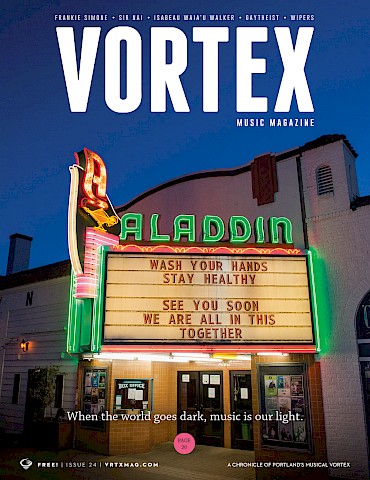

Working under the moniker Voodoo Catbox, Houston is the guy who creates annual screen-printed posters for Oregon Music Hall of Fame induction ceremonies and artwork for the Waterfront Blues Festival. He was finalizing designs for this year’s Fourth of July fest when it was officially called off on March 24, instead turning his attention toward documenting the timely marquee of the Aladdin Theater and hopefully creating a piece of merch that the venue can sell to help sustain itself during these trying times.

Gary Houston's work-in-progress scratchboard turns into 200 screen-printed posters documenting the Aladdin Theater’s marquee, for sale via the venue’s online store—click to learn more about his processIn the last month, our entire world has been separated into two categories: essential and non-essential. One category means, quite literally, food and shelter and medicine. The other is everything else. While we relish music venues, theaters and museums, it was an important mandate by Governor Kate Brown to deem them non-essential in March, because if she hadn’t, Oregon’s hospital beds and intensive care units would be overflowing in an unparalleled state of disaster.

Gary Houston's work-in-progress scratchboard turns into 200 screen-printed posters documenting the Aladdin Theater’s marquee, for sale via the venue’s online store—click to learn more about his processIn the last month, our entire world has been separated into two categories: essential and non-essential. One category means, quite literally, food and shelter and medicine. The other is everything else. While we relish music venues, theaters and museums, it was an important mandate by Governor Kate Brown to deem them non-essential in March, because if she hadn’t, Oregon’s hospital beds and intensive care units would be overflowing in an unparalleled state of disaster.

Thankfully, as I write this, they are not. (Although things could be very different depending on the day, as we all know!) We are lucky to live in a state that acted relatively quickly in the grand scheme of things. But our actions to socially distance, quarantine and self-isolate have led to the extreme devastation of multiple disciplines, fields and professions, including one that is particularly close to my heart: live music and the arts.

Nowhere in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs does it say we need music and poetry to reach self-actualization. But it does say that we need belonging. And for so many artists, belonging is found in the throngs of other humans, in the sweat of a live show, and in the ability to connect through their words and poetry, face-to-face in a dimly lit room somewhere in a small NE Portland pub, or in a sunlit backyard primed for a house show. And so, for so many of us who work in live music and the arts, we have been temporarily evicted from our spiritual homes, resolutely cut off from planning our futures.

For Oregon musicians, March 11 saw the precarious scaffolding and meticulous organizing that holds the fragile music industry together collapse within a matter of hours. Soon thereafter, festivals that we know and love, like Boise’s Treefort Music Fest and the annual Blues Fest, were postponed until later in the year or canceled altogether. Musicians that we know and love were forced to call off their bread-and-butter tours, nearly got stranded in Europe, and put on hold (or lost entirely) plans they’d been hatching for months or even years. The cavernous, concentrated loss inflicted a shocking amount of change overnight. Mourning is called for, no matter your situation.

Isabeau Waia’u Walker's debut EP comes out on April 26, and since she can't perform in front of a crowd, her "release show is going online" and will be live streamed on May 9: Photo by Adam LevyWhen devastation hits communities, there is a phase of grieving. In no particular order come shock and denial: “Things will be fine next month. This can’t last that long.” There’s also anger, depression and acceptance.

Isabeau Waia’u Walker's debut EP comes out on April 26, and since she can't perform in front of a crowd, her "release show is going online" and will be live streamed on May 9: Photo by Adam LevyWhen devastation hits communities, there is a phase of grieving. In no particular order come shock and denial: “Things will be fine next month. This can’t last that long.” There’s also anger, depression and acceptance.

These are all things that I have been grappling with while still presenting myself as a “strong band leader.” As someone who’s been in music for nearly a decade and spent the last couple of years working tirelessly towards an album release this spring, shifting my life around and finding bandmates who are ready for many miles on the road, the cancellation of it all has been a hard thing to wrap my head around and accept. And while I still don’t know what I’m doing, the future of live music being the murkiest that I’ve ever experienced, there is one thing that’s missing from the phases of grief that happen after acceptance, and that is adaptation and evolution.

The shock of the music industry collapsing is now slowly moving to my peripheral view, and it’s incredible to see how people have joined forces to protect and nurture one another, adapting quickly to a situation in which each step is as tenuous as the last. I feel strongly that musicians shouldn’t carry the burden of doing their own fundraising (although it’s fine if you want to, of course). We also don’t have to be the ones to fix anything: We, along with so many others, are experiencing firsthand the effects of the economic crash and deserve support.

Despite being the relative luddite that I am, technology is saving our butts. Online live streaming shows have taken off in popularity and, while they are no replacement for actual live shows in a beloved venue—monetarily or experientially—they’ve proven to be a fun outlet for both artists and fans, and a direct, easy way to support musicians. Relief funds from arts organizations, private and public, have sprung up across the country, with some in Oregon still accepting applications.

Companies like Spotify have partnered with the Recording Academy’s charitable foundation MusiCares to donate up to $10 million to relief funds. (Not that I’m quick to thank Spotify—it could pay artists a living wage at all times, but that’s another article.) Congress passed the CARES Act, which expands the limitations of unemployment insurance to cover gig workers and the self-employed (an improvement from the 2008 financial crash, during which said workers were left by the wayside). That, however, is also proving to be a challenging system to receive prompt support from.

Before March came to a close, MusicPortland surveyed 1,381 musicians and music professionals in Oregon who reported almost $7 million in lost revenue: Click to see the complete infographic by JP Downer of Motorobot CreativeOur local music advocacy group MusicPortland swiftly put together a survey capturing statewide data on lost revenue and income for working musicians, educators, recording engineers and other industry professionals, sending those results to the governor’s desk and lawmakers in Washington to help secure extra support. MusicPortland has also teamed up with organizations like emergency healthcare fund The Jeremy Wilson Foundation, our state's economic development agency Business Oregon, and the local chapter of The American Federation of Musicians (aka Musicians Union, Local 99) to spread knowledge about various resources for us artists.

Before March came to a close, MusicPortland surveyed 1,381 musicians and music professionals in Oregon who reported almost $7 million in lost revenue: Click to see the complete infographic by JP Downer of Motorobot CreativeOur local music advocacy group MusicPortland swiftly put together a survey capturing statewide data on lost revenue and income for working musicians, educators, recording engineers and other industry professionals, sending those results to the governor’s desk and lawmakers in Washington to help secure extra support. MusicPortland has also teamed up with organizations like emergency healthcare fund The Jeremy Wilson Foundation, our state's economic development agency Business Oregon, and the local chapter of The American Federation of Musicians (aka Musicians Union, Local 99) to spread knowledge about various resources for us artists.

In addition to these efforts, fans have stepped up to directly support their favorite musicians. Bandcamp saw record sales and pre-orders when it waived all fees on March 20, encouraging the artist-friendly platform to continue the practice on the first Friday of each month through July. Parts of the music industry may be folding in on itself, but we aren’t letting it do so willingly—and that is something to be proud of.

With all these support efforts rooting and blossoming essentially overnight, it’s tempting to say that we will be fine. It’s tempting to think that things will “go back to normal” once we create a vaccine for Covid-19. It’s already nostalgic to believe things will go back to the way they were. And while I don’t always have the most optimistic perspective, with my opinions generally erring on the side of sharp criticism, I do believe that we will be fine. But I don’t believe that we will be the same.

There’s been a visceral shift in the angling of the world. For starters, social distancing has exposed how broken the music industry is—independent artists cannot survive on album streams alone (looking at you, Spotify, Amazon, YouTube and Apple) and, in general, are not humanely compensated. Larger, corporate music industry companies like Live Nation (which owns Ticketmaster) and AEG (which puts on Coachella) will, unsurprisingly, come out on top, while us baby bands and local music industry folk will suffer.

"After five-plus years of monthly showcases, tonight is the first time we’ve ever had to cancel an edition of The Thesis," wrote DJ Verbz on Twitter, referring to the April concert of Portland's hip-hop monthly that he hosts at Kelly's Olympian: Photo by Anthony PidgeonConsider this warning: “Many independent venues will not survive without strong state and federal assistance,” writes local promoter True West Presents, which produces concerts at the Aladdin Theater, Revolution Hall and Oregon Zoo, in a recent call for support asking fans to contact local and state representatives to advocate for changes in the federal Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) so it will include wraparound support for small- and medium-sized music venues.

"After five-plus years of monthly showcases, tonight is the first time we’ve ever had to cancel an edition of The Thesis," wrote DJ Verbz on Twitter, referring to the April concert of Portland's hip-hop monthly that he hosts at Kelly's Olympian: Photo by Anthony PidgeonConsider this warning: “Many independent venues will not survive without strong state and federal assistance,” writes local promoter True West Presents, which produces concerts at the Aladdin Theater, Revolution Hall and Oregon Zoo, in a recent call for support asking fans to contact local and state representatives to advocate for changes in the federal Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) so it will include wraparound support for small- and medium-sized music venues.

“Music venues were first to close in this crisis, and they’ll be last to reopen,” points out Jim Brunberg, founder of Mississippi Studios, Polaris Hall and Revolution Hall, on Twitter. The limited terms of the “PPP won’t save Oregon’s venues. Assembly spaces will need several more months to get going again.”

“Performance venues are an essential part of life in Oregon, and the seventh biggest industry in the state,” Brunberg continues. “And they represent our largest cultural community—and we need your help.” It’s hard to stomach, but the landscape of independent music will be different from here on out.

I take comfort in admitting that I don’t know what is next. We may not have direct agency over how the music industry is structured, but we have agency over how we want to adapt with this shifting paradigm. We have experience as a species with reinventing ourselves to find happiness and success in whatever form that takes. That much is written into our DNA. And music, as always, will continue to be made because we have to make it. It’s what we’ve always done.

When the world goes dark, music is our light. Inspiring hope and offering perspective beyond overwhelming coronavirus stats, Vortex will continue to tell stories of our #PDXmusic community: CLICK HERE to subscribe and get a copy of the mag delivered to your door each quarter! Photo by Anthony PidgeonBrecht wrote To Future Generations in a very different political and ecological climate. But even still, I disagree with him that talking about trees is a crime. With the ecological pressures breathing down our necks as we navigate a new landscape of artistic production in a time of self-isolated capitalism and a global pandemic, I can’t think of a better time than now to keep in mind a piece of our planet that thrives not from the extinction of others, but from the coordinated codependence of community.

When the world goes dark, music is our light. Inspiring hope and offering perspective beyond overwhelming coronavirus stats, Vortex will continue to tell stories of our #PDXmusic community: CLICK HERE to subscribe and get a copy of the mag delivered to your door each quarter! Photo by Anthony PidgeonBrecht wrote To Future Generations in a very different political and ecological climate. But even still, I disagree with him that talking about trees is a crime. With the ecological pressures breathing down our necks as we navigate a new landscape of artistic production in a time of self-isolated capitalism and a global pandemic, I can’t think of a better time than now to keep in mind a piece of our planet that thrives not from the extinction of others, but from the coordinated codependence of community.

Disasters are prime environments for leaning into each other and trusting that we can indeed take care of each other. As one of my favorite writers, Rebecca Solnit, writes in A Paradise Built in Hell: “Disaster doesn’t sort us out by preferences; it drags us into emergencies that require we act, and act altruistically, bravely and with initiative in order to survive or save the neighbors, no matter how we vote or what we do for a living.”

I know, I just put out a song with the lyrics: “I can’t save you, and I sure as hell can’t save myself / ‘Advanced State of Decay’ is just another thing to argue about.” The pessimism of the song is meant to be a double negative, one that may induce reverse psychology so that we may consider: It is time for us to save our neighbors simply by being neighbors—in an awkward, distant kind of way.

By staying home, cheering on our essential workers and ordering the things we need online, we can make Mr. Rogers proud.

Punk rockers, save your anger for the coming days: We will need it. Funk rockers, we will need your rhythm and grooves to lift us up. Hip-hop artists, we will need your poetry to root us. Engineers, photographers, videographers and journalists, we will need your help to capture it all.

Songwriters, sing of trees. I am singing with you.

Olivia Awbrey is a songwriter, multi-instrumentalist and writer from Portland. Her debut LP 'Dishonorable Harvest' is out on her own Quick Pickle Records on May 1—pre-order it here.