Y La Bamba’s Luz Elena Mendoza: Photo by Pete LeeInspiration is a worm. It embeds itself into subterranean spaces of the brain and the artist’s job is to delicately extract it in one piece. That worm sometimes carries a story within it—a swirling fable, a lesson to relay, a testimony. Sometimes that worm transports raw emotion and to feel it when it arrives is nothing short of cathartic. Other times, the worm is a vessel for facts—information cleverly packaged in relatable evocation.

Y La Bamba’s Luz Elena Mendoza: Photo by Pete LeeInspiration is a worm. It embeds itself into subterranean spaces of the brain and the artist’s job is to delicately extract it in one piece. That worm sometimes carries a story within it—a swirling fable, a lesson to relay, a testimony. Sometimes that worm transports raw emotion and to feel it when it arrives is nothing short of cathartic. Other times, the worm is a vessel for facts—information cleverly packaged in relatable evocation.

When women create from their trauma and oppression, the work that surfaces is often a combination of all three of these elements: stories, feelings and knowledge.

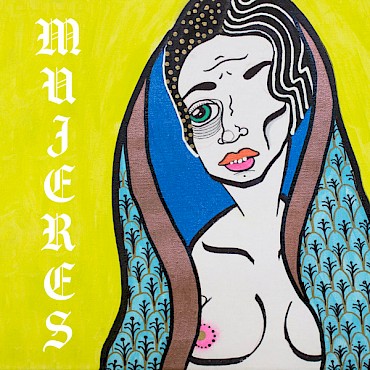

In the case of Luz Elena Mendoza and her band Y La Bamba, this inspiration triad seems to underscore the sound itself. A sort of mystic lore shows up in the music, where hypnotizing melodies and riffs dance together to take listeners on a journey. Her life’s triumphs and hardships seem to counterpoint one another on her fifth record, Mujeres, which is out this February on Portland’s Tender Loving Empire. The pursuit of knowledge transmission is also present. Hard-earned and sharpened through personal experiences, an intention to relay information rounds out this album as more than just good... it’s meaningful.

Women might feel especially inclined to stand up and move to the single and title track “Mujeres”—it’s a rallying anthem written as a response to misogyny, daring women to know and state their worth.

As a Mexican-American woman in her mid-30s, Mendoza is no stranger to the multifaceted ways that both racism and sexism have impacted her life. As a woman who’s long been involved in music, the realities within the industry and society at large that set the stage for the broader #MeToo conversation are ones that she knows intimately. We sat down together one evening in Portland to chat about intersectional feminism and the ways in which the fight for equality have affected her personal life, process and work.

I’m tired,” she tells me. She’s tired in a way that has nothing to do with sleep.

There is a weight of fatigue women like Mendoza carry. The quest to be heard has been long and exhausting. So much so that in the wake of #MeToo, it can feel disorienting to have people finally tell you to speak; it’s unfamiliar to have people tell you that they’re ready to listen.

“You mean this whole time, I was right? I don’t even know what to do with all of that,” she says, referencing the change in the air since #MeToo. It’s validating, but it’s also complicated.

Photo by Steffannie WalkMendoza and I are both women who came of age, in many senses, amid the Riot Grrrl movement of the ’90s. In a concentrated way, Riot Grrrl groups like Bikini Kill, Bratmobile, Team Dresch and Sleater-Kinney helped a lot of women feel empowered. It made “girl” less of a dirty word, for one. And most relevant to #MeToo, it showed women how to take ownership of their bodies and expect accountability for those who violate the boundaries they set.

Photo by Steffannie WalkMendoza and I are both women who came of age, in many senses, amid the Riot Grrrl movement of the ’90s. In a concentrated way, Riot Grrrl groups like Bikini Kill, Bratmobile, Team Dresch and Sleater-Kinney helped a lot of women feel empowered. It made “girl” less of a dirty word, for one. And most relevant to #MeToo, it showed women how to take ownership of their bodies and expect accountability for those who violate the boundaries they set.

I spoke with Sady Doyle, author of Trainwreck: The Women We Love to Hate, Mock, and Fear... and Why, for some clarity and context on how Riot Grrrl equipped us for #MeToo.

Riot Grrrl was really instrumental for a ton of women in terms of naming and processing their sexual abuse history. This is at the root of so much of the activism today,” she explains.

But the movement had its shortcomings, which Doyle was quick to mention.

“It was Pacific Northwest indie culture and it had the limitations of that subculture, including really extreme whiteness. Women of color were always present, but the image of the movement was very much that of a white punk girl and that became self-perpetuating as the white image made other women feel unwelcome or turned off.”

Though it was a powerfully mobilizing chapter in feminism, the fact that the fight is still here and happening decades later, particularly for women of color, is part of the reason why Mendoza is tired.

Y La Bamba performing at Pickathon in 2017—click to see more photos by Sam GehrkeAs #MeToo has taken hold, a lot of murmurs have been circulating in the music industry. Whether we’re talking about widely known mainstream music examples—take Kesha and her terrifying experience of being contractually forced to work with the producer, Dr. Luke, who she accused of abuse and rape—or lesser-known incidents that inevitably encircle so many women involved in the music industry at every level, the question is begging for an answer: When will we finally address the rampant sexism in music?

Y La Bamba performing at Pickathon in 2017—click to see more photos by Sam GehrkeAs #MeToo has taken hold, a lot of murmurs have been circulating in the music industry. Whether we’re talking about widely known mainstream music examples—take Kesha and her terrifying experience of being contractually forced to work with the producer, Dr. Luke, who she accused of abuse and rape—or lesser-known incidents that inevitably encircle so many women involved in the music industry at every level, the question is begging for an answer: When will we finally address the rampant sexism in music?

There are so many issues to unpack on why this industry is taking longer to reach accountability than others, but the inherent “cool girl” role as a means of entry to the industry is a start. The music industry is reliant on coolness and the “cool girl” doesn’t make a big deal out of things, right? More to the point, women in music have long been put in a position to be over-sexualized or simply overlooked, counted amongst the men. And still, in the case of the latter, no amount of neutrality in gender-signaling can prevent women in music from being filtered as such, first and foremost. “Female-fronted” and “girl band” are still commonly used terms in the industry, often interchangeable with an actual genre. Imagine seeing the inverse for every applicable instance of men in music: No one’s ever been called a “male-fronted” band.

“There’s a lot of code-switching going on,” says Mendoza when I ask her about the “cool girl” problem within music.

Women have to regularly speak to men in music differently—from the sound guy and the recording engineer to the label representatives and even at times, sadly, their own bandmates. A degree of demurity, dumbing down and deference is regularly expected, and a lack thereof can quickly corner women into “bossy” and “bitch” territory. That women might play the role they’re asked to isn’t duplicitously devious, by the way: It’s a mandatory way of existing that facilitates being heard and seen by a tried-and-true boys’ club.

“I’ve been coddled. I’ve been manipulated,” Mendoza tells me. “I made myself small for a lot of reasons,” explaining how she spent years deferring to others’ opinions, especially in music.

In an interview with Bust, Mendoza once said, “I write in Spanish because it wants to be sung, I write in English because it wants to be said.” That powerful sentiment encapsulates the gist of this release as well. Mendoza doesn’t just dance between melody and declaration with her words, but with all aspects of Mujeres. Loose and ethereal rhythms perfectly set the stage for charged hip-shaking beats. Her titular single’s call to women delivers a message of humanity and cooperation while still being courageous and stern. Her joy flows freely amid her clearly stated pain.

“I fucking went through it. And now I’m here.”

Photo by Pete LeeTo contextualize her struggle with men as one that was nearly impassable, she reveals a childhood disrupted by domestic violence. “I’m here where I’m at because of fighting all of those voices.”

Photo by Pete LeeTo contextualize her struggle with men as one that was nearly impassable, she reveals a childhood disrupted by domestic violence. “I’m here where I’m at because of fighting all of those voices.”

We talk for a while about how growing up with oppression and abuse can simultaneously make a person both hyper-vigilant in their alertness to inequality and susceptible to toxicity. When you’ve made it to the other side of any type of pervasive and ongoing inequality, you’re eager to never lose your footing again, which can position you to become an advocate. But, in contrast, experiencing extreme conditions—like chronic abuse—can distort where a person’s bar for tolerance should be set.

Sometimes we’re running on fumes. Sometimes we’re drowning in our own fuel.

Mendoza oscillates from trying to pick her battles to seeing everything as a battle. Her intention isn’t at all to operate in a way that is divisive, though. She’s still working on how she articulates things to the people who she hopes are or can become allies. She’s learning how to hold everything beneath an umbrella of unconditional love.

“I need space to really figure out my trauma,” she says. Once she and others are given the room to reflect and process, hearing ears are needed. Whether we’re talking about someone who is enjoying Y La Bamba’s songs or a person who witnesses Mendoza’s advocacy on equality outside of music, the kind of hearing she wants requires active listening. “That means that you have to do work and see your ego. That means that you have to do work and see where your entitlement is.”

As the climate continues to change amid #MeToo, she’s breathing through it all as she needs to. She’s also celebrating the progress being made and that truth is depositing bits of itself into all aspects of her life.

“If I’m changing, everything else I’m doing is going to change,” she says, referencing how strides toward equality are woven into her newest music, which she spearheaded the production on for the first time in her career. “No man ever told me I was a producer,” she says. She had to figure that much out on her own and once she did, it unleashed an entirely new power within her, as evidenced by Mujeres.

Celebrate the release of Y La Bamba's fifth LP 'Mujeres' on Tender Loving Empire at Revolution Hall on February 9There’s strength in community that can catapult us all forward. We all need to show up for one another, far past the perimeters of music. Mendoza drives this point home as we continue to chat.

Celebrate the release of Y La Bamba's fifth LP 'Mujeres' on Tender Loving Empire at Revolution Hall on February 9There’s strength in community that can catapult us all forward. We all need to show up for one another, far past the perimeters of music. Mendoza drives this point home as we continue to chat.

“My community reminds me of loving myself,” she says, and then adds that this is what she considers to be fundamental to a community’s core: helping everyone in it remember that they matter.

The best way we can all move toward a more equitable future might just be through our communities. We need to gather with one another and learn what members of our respective communities need. We must listen and make space with love. And we should honor the artist within each of us by not only sharing our stories, feelings and knowledge, but by being receptive to those offerings from others as well.

It’s simple, but what we need most for #MeToo, music and all other facets of our realities might just be the thing that makes Mujeres such a beautifully authentic creation.

“That record is communication,” Mendoza says.

Communication. Could it be that easy?