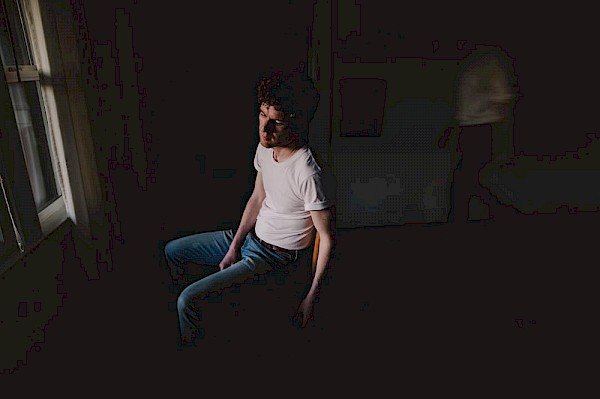

Lorain's frontman and guitarist Erik Emanuelson: Photo by Kim Smith MillerMemory is a funny thing. We tether our lives to people and places and lay down autobiographies—stories we tell ourselves and others about where we come from and who we are. When we crave a sense of renewed energy or want to start over, we travel and relocate. Sometimes, we want to disappear, reinvent ourselves, or be reimagined, and so we change our name.

Lorain's frontman and guitarist Erik Emanuelson: Photo by Kim Smith MillerMemory is a funny thing. We tether our lives to people and places and lay down autobiographies—stories we tell ourselves and others about where we come from and who we are. When we crave a sense of renewed energy or want to start over, we travel and relocate. Sometimes, we want to disappear, reinvent ourselves, or be reimagined, and so we change our name.

That’s how it was for Lorain (formerly Grand Lake Islands), as frontman and guitarist Erik Emanuelson explains: “We had written a song that seemed different stylistically—it didn't really fit what we were doing and we decided to change our name to mark that stylistic shift.” That song was a tribute to Jason Molina, a singer-songwriter whose music had a profound effect on Emanuelson and Lorain’s drummer, Bob Reynolds.

“We wanted something that was simple and classic sounding, and we thought, ‘How about Lorain?’” As Emanuelson tells it, “The song mentions Lorain, Ohio, in the lyrics—it's where Jason Molina was from—and it kind of stuck.” They renamed the sound-altering song “Midwest Red” and the band collectively adopted Lorain for themselves.

Oddly enough, Molina had done a similar thing in his own career. He released music as a solo project with a rotating cast of musicians under the name Songs: Ohia, then he recorded a career-defining album, Magnolia Electric Co., and renamed the band after it, connecting the past to the next phase of his music.

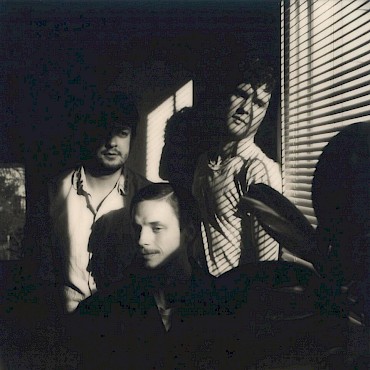

Photo by Kim Smith MillerThe country-rock sound of Molina’s music was posthumously described by his younger brother Aaron as “a combination of rural and city… that is really what Lorain is.” It’s also a beautifully analogous description of the themes and sonic landscapes on Through Frames, the debut album from Lorain—eight hazy, lyric-driven songs about lonesome country and the blinding metropolis—a rural sound for modern life.

Photo by Kim Smith MillerThe country-rock sound of Molina’s music was posthumously described by his younger brother Aaron as “a combination of rural and city… that is really what Lorain is.” It’s also a beautifully analogous description of the themes and sonic landscapes on Through Frames, the debut album from Lorain—eight hazy, lyric-driven songs about lonesome country and the blinding metropolis—a rural sound for modern life.

The echoed imagery of smoke and shadows cast amorphous outlines of loss, while concrete visuals of “darkness around cigarette light,” “a bruised sky” and “bruised-up friends” sharpen the details. Lorain’s sound is like hard twilight glinting off a dusty windshield, a rain-swept prairie, the warm and soothing drone of tires on paved road rolling towards a foreign and endless horizon. It’s the kind of album you play in the car on a road trip as you leave home, on a night drive lit by a sickle moon and stars, or a sleepless wander under the kaleidoscopic glare of illuminated signs and passing street lights.

“Midwest Red” resonates those themes. “It was something that Jason Molina wrote about a lot and experienced. Being on the road and describing the landscapes around him as a metaphor for his emotions.”

Through Frames was also inspired in part by The Lonely City: Adventures in the Art of Being Alone by Olivia Laing, a memoir that explores New York, the depth of heartbreak and “the essential unknowability of others” through the work of artists and cultural figures. It’s a meditation on the notion that to be human is to be lonesome sometimes, even in a crowded city where one experiences an “uneasy combination of separation and exposure.”

Through Frames makes plenty of glimmering references to the glass frames we stare into and out of from a "blue television frame," "the rose window," “a cracked window,” to a description of apartment buildings as "towers of aching yellow light, strung up above the city floor."

“It’s where the idea for the album name and the song came from—sort of picturing a couple of heavily windowed glass apartment buildings, maybe across the street from each other—an almost voyeuristic sense of being able to see people all the time and this weird sense of knowing so many things about people but really not knowing them at all. For me, that tied heavily into the idea of what's going on now with social media and how we see so much of people but know so little of who they really are.”

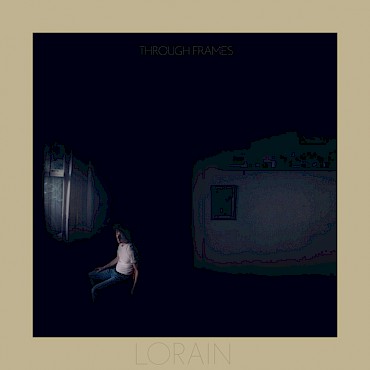

Celebrate the release of Lorain's debut album 'Through Frames' at The Liquor Store on September 26The title track muses on our devices with the forlorn question, “Was I asking for their eyes, to see on through the haze of the smokescreen I slide into the pockets of my jeans? Oh the gulf can be, so dark and deep.”

Celebrate the release of Lorain's debut album 'Through Frames' at The Liquor Store on September 26The title track muses on our devices with the forlorn question, “Was I asking for their eyes, to see on through the haze of the smokescreen I slide into the pockets of my jeans? Oh the gulf can be, so dark and deep.”

“All the songs on this album come from that emotional place,” says Emanuelson, “the idea that loneliness, solitude and isolation are this triad of things and they all kind of mean the same thing, but have drastically different connotations.” The soft sprawl of solitude, the hunger pang of loneliness and the stropped edge of isolation that hones a person into a self-defeated weapon are decidedly all quite different.

Emanuelson elaborates at length on the subtleties: “Solitude or aloneness are things we use to explore the outer edges of ourselves. It's a good thing and it can be a really restorative thing, but within those outer edges there's the shadow of this feeling of isolation. It's equally important to get into that zone and a lot of songs are about looking back at everything from that vantage point. Be it looking at yourself, stepping outside of yourself and looking at how your own insecurities are tarnishing your view of the world around you, or stepping back and looking at how someone that you know very well and care about is experiencing a strong sense of isolation.”

Emanuelson takes the exercise of looking back and sings about his own hometown on “Tobacco Valley,” a place of worldwide renown with the perfect climate for growing the outermost wrapper of pale caramel leaves used by high-end cigar brands like and Arturo Fuente, Davidoff and Macanudo. It’s not an automated process; the plants, like people, demand a lot of direct attention and are tended to and harvested by hand. Like a town that loses its lustre when tastes change, an increase in the popularity of dark-wrapper cigars like Maduro led to a decline in consumer demand for lighter-colored shade tobacco. The politics of anti-smoking sentiment, arguments over land development, foreign competition and labor costs only added to economic downturn and the threat of the century-old iconic crop of the Connecticut River Valley vanishing from the state's landscape.

More poignantly, Emanuelson talks about the house his mother lived in by herself while in the process of trying to sell it, and the feeling that the house he grew up in had changed somehow, even becoming a little oppressive. “My family had been going through a lot of stuff in my childhood home.” Emanuelson recalls, “At one time, it was a place that one associates with home and comfort, safety and certainty, and the gradual shift away from that with my mom and the circumstances of her marriage, relatives passing away—that place becomes a lot more lonely. Kind of a ghost of itself and not really a place that holds the memory of those things. That feeling of ‘stayed too long at the fair’ so to speak, where things start to sour a bit.”

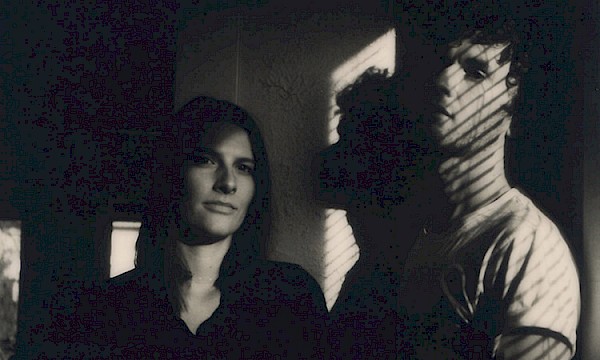

Robin Bacior and Emanuelson: Photo by Kim Smith MillerYou can hear the loss of home and sense of place in the song accordingly. With languid and spare instrumentation from Reynolds on drums and Mitch Gonzales on bass, “Tobacco Valley” (listen below) thumps softly along, a melancholic heartbeat with Emanuelson’s watery, pulled-apart guitar hook that is both sweet and immediately familiar—a taffy souvenir you long for that reminds you faintly of the ocean. Bandmate Joseph Anderson (piano, organ, synth) adds muted keys, trilling out a lazy alarm bell that twinkles out a music box lullaby like a dream that needs constant rewinding. Emanuelson breaks the spell mid-tune with a commanding and ghostly moan to sing, “There’s a hole where a lake used to be, the bones of a once loved thing,” while Robin Bacior illuminates the choruses and minor to major dissolves with ethereal harmonies.

Robin Bacior and Emanuelson: Photo by Kim Smith MillerYou can hear the loss of home and sense of place in the song accordingly. With languid and spare instrumentation from Reynolds on drums and Mitch Gonzales on bass, “Tobacco Valley” (listen below) thumps softly along, a melancholic heartbeat with Emanuelson’s watery, pulled-apart guitar hook that is both sweet and immediately familiar—a taffy souvenir you long for that reminds you faintly of the ocean. Bandmate Joseph Anderson (piano, organ, synth) adds muted keys, trilling out a lazy alarm bell that twinkles out a music box lullaby like a dream that needs constant rewinding. Emanuelson breaks the spell mid-tune with a commanding and ghostly moan to sing, “There’s a hole where a lake used to be, the bones of a once loved thing,” while Robin Bacior illuminates the choruses and minor to major dissolves with ethereal harmonies.

Similarly, Bacior and Emanuelson are solid and complementary partners that drift in and out of each other's music projects. “We're doing a tour in Europe in a few weeks. It's going to be mostly her and me in Italy, first for two weeks for her music, and I'll be playing guitar there,” Emanuelson says, “then we'll be switching to Lorain music and going to Germany, Austria and Switzerland and playing as a duo with Joseph flying out to some of the shows to play keyboard. It’s exciting. It's going to be amazing.”

There have been several comparisons to Bob Dylan throughout Emanuelson’s work, but like the band name, the process and the writing style has changed.

“I'm a very big Dylan fan obviously, I still am. One thing that I feel like I've gleaned musically in the progression from my last project to this one is an economy of language. I think I used to be really into this idea of just cramming as many words in a Dylan-esque way, almost like a rap of sorts. I think economy of language is something that I’ve really grown into and what's cause me to drift a little away from Dylan. As far as instrumentation too, we really tried to take a lot out that didn't seem essential.”

Emanuelson attributes that to his bandmates. “Bob and Joseph are very much a part of that. It's one of those situations where I go with the song and I think of how I want it to sound, and it always sounds outside the realm of where I thought it was going to go, and always for the better. We have a pretty good process of writing and I really enjoy their collaboration.”

Through Frames is a delicate and masterful exploration that encapsulates both the time-worn and contemporary intricacies of life—the people we love and we lose, the cities and houses that hold our memories, the glass frames and social media that we view the world and each other through, and the places we travel to and from that help us discover and remember who we are.

Through Frames is a delicate and masterful exploration that encapsulates both the time-worn and contemporary intricacies of life—the people we love and we lose, the cities and houses that hold our memories, the glass frames and social media that we view the world and each other through, and the places we travel to and from that help us discover and remember who we are.