Norman Sylvester surveys the Waterfront Blues Festival crowd for the umpteenth time—he played the inaugural fest in 1987 and almost every year since: Photo by John AlcalaUp on the stage at NE Portland’s Spare Room on a Saturday night, Norman Sylvester played some deep blues on his Stratocaster, creating pitch-bending, stinging, single-string leads that he interwove with his pleading, sometimes raspy, sometimes silken voice.

Norman Sylvester surveys the Waterfront Blues Festival crowd for the umpteenth time—he played the inaugural fest in 1987 and almost every year since: Photo by John AlcalaUp on the stage at NE Portland’s Spare Room on a Saturday night, Norman Sylvester played some deep blues on his Stratocaster, creating pitch-bending, stinging, single-string leads that he interwove with his pleading, sometimes raspy, sometimes silken voice.

I’ve been downhearted

Ever since the day we met

Our love is nothing but the blues

How blue can you get?

The almost 73-year-old bluesman sang the B.B. King classic with an aching growl. (Editor's Note: Today, he's 74. And he shares his birthday, September 16, with B.B. King, to boot! Born exactly 20 years after, King was born in 1925.) But he didn’t just play the typical repertoire. Interspersed with the Delta blues was the electrifying stomp of Muddy Waters and the Chicago blues of Jimmy Reed. There were funky songs from New Orleans—The Meters’ ‘“Cissy Strut” and The Neville Brothers’ hypnotic “Fiyo on the Bayou.” To show they weren’t purists, the quartet did a funked-up medley of Parliament’s “Give Up the Funk (Tear the Roof Off the Sucker),” the Ohio Players’ “Fire” and Morris Day’s “Jungle Love.” Sylvester—looking satisfied in his dapper white suit and red tie, red hat, and red-and-white spats—played the jam-packed club like it was a backyard barbecue.

“Can I get some help in the house?” the Boogie Cat asked early into his first set, smiling slyly. The blues revelers came back with a roar of clapped hands in sync to the rhythm. The dance floor was chockablock and bristling with energy.

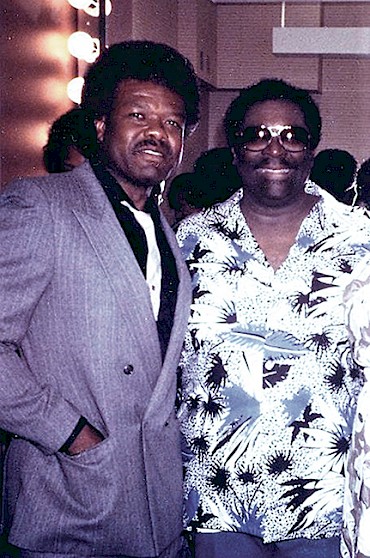

The Boogie Cat with B.B. King in 1987In Portland, Sylvester is a legend. For a quarter century, he’s played the Waterfront Blues Festival as well as jammed with, or opened for, blues giants Buddy Guy, Albert Collins and B.B. King. It was King in 1987 who told a 42-year-old Sylvester, then a teamster for the trucking company Pacific Intermountain Express, to devote himself full time to music. A few years later, Sylvester heeded his advice when he lost his job and had nothing but music to fall back on. In his first major gig after being laid off, he opened for B.B. King and Buddy Guy at the Eugene Blues Festival in ’91. After that, he never looked back because his phone didn’t stop ringing.

The Boogie Cat with B.B. King in 1987In Portland, Sylvester is a legend. For a quarter century, he’s played the Waterfront Blues Festival as well as jammed with, or opened for, blues giants Buddy Guy, Albert Collins and B.B. King. It was King in 1987 who told a 42-year-old Sylvester, then a teamster for the trucking company Pacific Intermountain Express, to devote himself full time to music. A few years later, Sylvester heeded his advice when he lost his job and had nothing but music to fall back on. In his first major gig after being laid off, he opened for B.B. King and Buddy Guy at the Eugene Blues Festival in ’91. After that, he never looked back because his phone didn’t stop ringing.

“Music blessed me with happiness, prosperity and fulfillment,” Sylvester says. “I’m always busy, whether I’m playing clubs and festivals or teaching in the schools. I never worry about money.”

He’s never taken his gift for granted either. He knows the music is about diving deep into the territory of one’s soul.

“When I first heard the blues, I saw the tear-stained eyes and heard the mournful cries of people in bondage,” Sylvester says sitting in the studio he built behind his North Portland house where his band practices. There, with a drum set, mixing board and effects pedals, he presides over a photographic history rich with memories.

“The blues was the music the slaves carried from Africa,” he begins. “But the guitars and harmonicas were about freedom and transcendence. Most of the blues singers I hear are searching for the sweetness of the old blues, the old phrasing. That’s so crucial to the music’s power. Musicians are messengers. We take the rhythms and the melodies and heal people.”

For Sylvester, not surprisingly, the blues is a practice. So every day he immerses himself in some form within the music. He practices with a metronome for phrasing and timing and listens to the music of the great bluesmen, like King and Muddy and Buddy Guy. What he’s looking for is subtle. It’s essence, not technique. It’s the flash of spirit.

“I listen to their licks and pick out the ones that speak to me. I let this historical way of playing the guitar enhance my style.”

Some weeks he’ll listen to B.B. King; other weeks he might groove on Albert Collins. And some weeks he listens to gospel.

“That’s what R&B is: a mix of gospel and blues,” he says as if announcing a mathematical theorem.

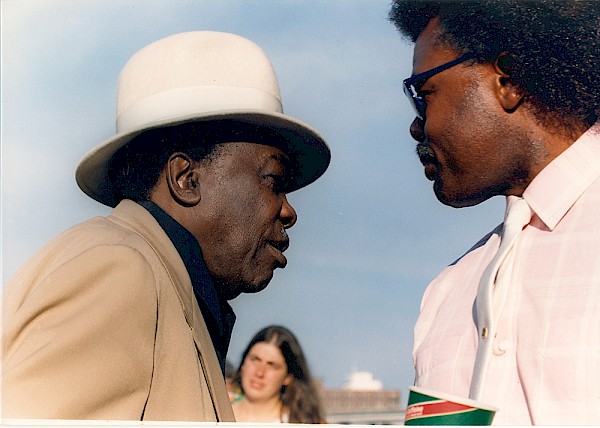

The Cascade Blues Association sponsored the first Rose City Blues Festival (now Waterfront Blues Festival) in 1987 and the Norman Sylvester Blues Band performed alongside John Lee Hooker (pictured), Paul deLay Band, Curtis Salgado, and The Lloyd Jones StruggleSylvester was born in Bonita, La., in 1945 on a 110-acre farm owned by his grandmother, who was a midwife and brought him into this world. His earliest musical influence came from hearing gospel singing in church and blues sung by itinerant performers in the community. His father Mack Sylvester and Uncle John sang in a gospel group called the Spiritual Five who toured around Northern Louisiana and were broadcast on the radio every week in Monroe, La.

The Cascade Blues Association sponsored the first Rose City Blues Festival (now Waterfront Blues Festival) in 1987 and the Norman Sylvester Blues Band performed alongside John Lee Hooker (pictured), Paul deLay Band, Curtis Salgado, and The Lloyd Jones StruggleSylvester was born in Bonita, La., in 1945 on a 110-acre farm owned by his grandmother, who was a midwife and brought him into this world. His earliest musical influence came from hearing gospel singing in church and blues sung by itinerant performers in the community. His father Mack Sylvester and Uncle John sang in a gospel group called the Spiritual Five who toured around Northern Louisiana and were broadcast on the radio every week in Monroe, La.

“The blues and gospel were interconnected,” he recalls. “They came from the same root.”

He started playing guitar when he was 15.

“It was 1960 and my father bought me a $12 acoustic guitar. He told me that if I learned three songs he’d buy me an electric guitar. And he was good to his word. He bought me a black Les Paulish-looking mail order catalog electric guitar for $99—and an amplifier.

“I played that guitar every day. My first live gig was in 1963 at the Best Western Multnomah hotel. It was a private party and I was thrilled to be on stage. The saxophonist was a busboy and the drummer and the guitarist were the dishwashers.”

The Norman Sylvester Band celebrated 30 years of the Cascade Blues Association alongside local blues legends Duffy Bishop and Lloyd Jones at the Crystal Ballroom in May 2017—click to see more photos by John AlcalaThe music came easily to him. He was ear-trained. If he heard it, he could play it. He could hear the blues too, whenever he wanted, on the all-blues jukebox at Jetty Mae’s Café in Bonita. And soon he found himself working hard to forge his own voice and style.

The Norman Sylvester Band celebrated 30 years of the Cascade Blues Association alongside local blues legends Duffy Bishop and Lloyd Jones at the Crystal Ballroom in May 2017—click to see more photos by John AlcalaThe music came easily to him. He was ear-trained. If he heard it, he could play it. He could hear the blues too, whenever he wanted, on the all-blues jukebox at Jetty Mae’s Café in Bonita. And soon he found himself working hard to forge his own voice and style.

“The thing is, I was a shy kid with a Southern drawl, which I got made fun of for. But I’d practice the guitar in front of a mirror to give me confidence and let me see what I looked like.”

At his grandmother’s farm, where cotton and sugar cane was grown, he heard field hollers and gospel. But the blues, Sylvester noticed, was balled up inside that sound. It came blended.

“You’ve got moans in the blues and moans in gospel. There was a call and response I heard in hollers from the fields. It was a beautiful thing to witness.”

His grandmother didn’t play the blues. She tolerated country and western music. For her, he sang innocent Hank Williams’ songs a cappella.

“For my grandmother, the blues was the devil’s music. But for me it was a ticket to freedom. I looked for the killing sound of the guitar, the sustained sweetness of tone and pulse of rhythm,” Sylvester recalls. “The blues came from Africa, from the heartbeat of the drum. But the rhythm was in the whip’s lashes too. That’s a painful truth.”

The family boarded a Union Pacific Vista Dome train in 1957 and moved to North Portland, settling on Borthwick Avenue. Sylvester went to Boise-Eliot Elementary and Jefferson High School where he ran hurdles on the track team and lettered. He was an average student but by the time he was 16, he knew he wanted to be a musician.

“I saw my dad as a performer. So he was a role model. My mother sang in the choir and all my sisters sang. I was surrounded by music growing up.”

And music continues to be a family affair with his wife Paula Sylvester, aka Mrs. Boogie Cat, providing ever-present support because “a musician's wife is also [a] roadie, social media person, photographer, product sales manager and biggest fan!” she exclaims, while their oldest daughter Lenanne Sylvester-Miller has sang on and off with her father for decades and other family members have also joined him on stage at various events.

Norman Sylvester and daughter Lenanne Sylvester-Miller harmonizing at the 2014 Oregon Music Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony at the Aladdin Theater—click to see more photos by John AlcalaTo date, Sylvester has played well over 4,000 gigs. He’s headlined Portland’s Rose Festival, the Mt. Hood Jazz Festival, Good in the Hood, and Seattle’s Bumbershoot. He’s played the prestigious Waterfront Blues Festival nearly every year since the inaugural fest in 1987 and performed with the Oregon Symphony.

Norman Sylvester and daughter Lenanne Sylvester-Miller harmonizing at the 2014 Oregon Music Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony at the Aladdin Theater—click to see more photos by John AlcalaTo date, Sylvester has played well over 4,000 gigs. He’s headlined Portland’s Rose Festival, the Mt. Hood Jazz Festival, Good in the Hood, and Seattle’s Bumbershoot. He’s played the prestigious Waterfront Blues Festival nearly every year since the inaugural fest in 1987 and performed with the Oregon Symphony.

Always spectacularly dressed, Sylvester's sharp fashion sense comes from “growing up in the South around hard-working family men (my father Mack and my four uncles) who always dressed to the nines for weekends and church,” he tells. “I was taught to always present myself the best I could be to help break down any barriers of acceptance. People will approach and talk to a well-dressed man without hesitation.” He also took a cue from blues pioneers like King and T-Bone Walker: “When I enter the venue, I want everyone to know I'm there to perform and entertain them with style.”

In between fests, he appears at clubs all over Oregon and Washington, teaches blues history in public schools, and performs gigs at assisted living homes and corporate events. From time to time, he’s even performed in prisons. When he talks about that a note of sadness creeps into his voice.

“I played at the Oregon State Penitentiary in Salem twice—performed before the whole prison. There were hundreds of men. And I was surprised that so many people knew of me in the prisons. I found friends of mine in the Oregon State Penitentiary from back in the day. The prisons are full of African Americans. The prisons are the new plantation. People of color get trapped in the system and are still in servitude. These prisons are traded on the stock market. They’re a huge business now.”

Norman Sylvester is also an outspoken advocate for Health Care for All Oregon, hosting annual benefit concerts including this summer's Soul Queens & Blues Kings at the Aladdin Theater on August 22The schools, he says, are the most rewarding. He made a resolution in the year 2000 to teach in public schools and started at Boise-Eliot, working alongside a teacher devoting time to civil rights history.

Norman Sylvester is also an outspoken advocate for Health Care for All Oregon, hosting annual benefit concerts including this summer's Soul Queens & Blues Kings at the Aladdin Theater on August 22The schools, he says, are the most rewarding. He made a resolution in the year 2000 to teach in public schools and started at Boise-Eliot, working alongside a teacher devoting time to civil rights history.

“I would come in and show how the music speaks to freedom. In West Linn, I’d do an assembly three or four times a year.”

Currently, he’s an artist-in-residence at Portland’s Irvington school (thanks to a Regional Arts & Culture Council grant), where he teaches songwriting.

“We’ll work with youth and turn their words into a ballad, spoken word, hip-hop or blues. The kids come out with jewels and we do a full-day recording session once a year. Last summer there were 13 original songs that came out on a CD we burned.”

Now that all seven of his kids are grown, the Oregon Music Hall of Famer says he’d like to set up a mini-tour and play in Europe. He’d like to play the King Biscuit Blues Festival in Arkansas, too.

“I’ve got a lot of first cousins in that area who I’d like to see,” he says. “And I have one aunt who’s 96 in Bastrop, La., and she is as sharp as ever. She’s my oldest living elder.”

He takes a long view of the music. He laments the loss of spirit in some commercial pop music. But he sees most of the street poets, the rappers, as a positive development.

“I see them as the Marvin Gaye and Bob Dylan of the day. I see them as protest music. Their sound comes from hard ghettos and it carries a hard message. Music is an emotional vehicle to the soul. It’s an intimate person-to-person conversation. That’s something that will never be lost.”