A two-time Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductee and Grammy award-winning songwriter, Graham Nash requires little by way of introduction. Hailing from Manchester, England, Nash would first team up with childhood friend Allan Clarke to form The Hollies, a group marrying a sharp pop sensibility with vocal harmonies inspired by the Everly Brothers to reach the forefront of post-Beatles English rock and roll. Nash would subsequently leave The Hollies following a rekindling of his friendship with David Crosby at the Los Angeles home of counterpart and then-lover Joni Mitchell in 1968. Shortly thereafter, Crosby and Nash would join forces with guitarist Stephen Stills and Stills’ former bandmate, Neil Young, upon the demise of Buffalo Springfield. Performing as Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, the ensemble would go on to appear at the 1969 Woodstock festival and release a series of landmark albums, most notably the eponymous debut (as Crosby, Stills & Nash) and 1970’s Déjà Vu, which remain the pinnacle of the American folk-rock canon.

As a songwriter and musician, Nash’s renown is certainly deserved. However, the broad scope of his artistic prerogative nevertheless merits wider attention. While an avid painter and sculptor, Nash’s photography is perhaps the most compelling of his non-musical artistic pursuits. As related in Wild Tales: A Rock & Roll Life, his 2013 autobiography, Nash appropriated this interest from his father, also a keen photographer, who gifted Nash, then 10 years old, a camera before he first handled a guitar. Nash has since indulged this facet of his creativity on an unceasing basis, taking several prominent portraits of associates like Crosby, Stills, Young and Mitchell, and of himself. In 1991, Nash would found Nash Editions, a fine art digital imaging and printmaking outfit whose first inkjet printer, a modified IRIS 3047, currently resides in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. His most recent photographic compendium, Love, Graham Nash, was published in 2010.

Interviewed in advance of his Saturday, July 18 performance at Portland’s Aladdin Theater, Nash speaks to the creative impulse inspiring his run of solo performances and discusses his affiliation with the Guacamole Fund, a nonprofit supported by the likes of Nash, Jackson Browne and Bonnie Raitt. Nash also reflects on the broader qualitative aspects of digital music technology, the characteristic duality of Neil Young, and the nature of their oscillating partnership. After recalling David Crosby’s introduction of jazz harmony into the CSN creative dynamic, Nash closes by disclosing hopes for a reunion and a forceful pronouncement in support of the group’s ongoing vitality.

What prompted this run of solo dates?

Graham Nash: I’ve been involved in the music of Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young continuously for the last, gosh, six or seven years. We have ownership of every show and everything we recorded, and I’ve done much of it with CSN, particularly. And I spent the last four years putting out the CSNY boxed set—the four CD boxed set with the vinyl and stuff. So I’ve been involved in our music for a long time.

Now it’s time for me. With my friend Shane Fontayne, who is the second guitar player in the Crosby, Stills & Nash band, we wrote 20 songs together and recorded those 20 in eight days. So I want to get out there and make my music!

It’s very interesting not having to think about David [Crosby] or Stephen [Stills]. You know, “I want an equal amount of songs in the show”—that kind of stuff. It’s very interesting not having to think about David or Stephen’s music.

In your autobiography, Wild Tales, I recall that you discussed the first time you performed solo—without David or Stephen—and how challenging it was, as it would be for anybody. Do you feel more comfortable in a solo format now?

I do. I think the more mature you get—in my case—the more comfortable I am. And I am pretty comfortable. Don’t forget, that was Stephen that said we were scared shitless at Woodstock. [Laughs]

Right [laughs]. Generally speaking, is that challenge more related to nerves? Or is it more readily attributed to the process of having to go rearrange a set of songs written for a group?

No, I’m pretty cool with all of it! I have a tremendous amount of songs I’ve written in my life. Of course, a great many of them are pretty well-known, particularly to my audience. So I feel like I’m going to go out there and I’m going to have the best time that I can.

Really, the point is that whenever anyone comes to see me… whatever they did in their entire lives—and that must be, what, like a billion actions per person?—they will bring those experiences to the Aladdin Theater, so why not have a great time?

Young, Stills, Crosby & Nash

Young, Stills, Crosby & Nash

I’ve read that some proceeds from the Portland performance will go to charity. Is it the Guacamole Fund that you’re currently supporting?

We have worked with Tom Campbell and the Guacamole group for 40 years! And yes, a part of that is for them.

Is the Guacamole Fund the focal point of your activism now?

It’s just the one organization that we have always trusted. Probably 95 percent of the benefits that me, or David, or Stephen, or Neil [Young], or Jackson [Browne], or Bonnie [Raitt] ever did were done with Tom Campbell and Guacamole.

Oh, interesting. So there’s crossover there.

Oh, yes! There’s a lot of trust there. We know where every dollar goes, and we know that they’re operating on a shoestring. We know all that. They’re well worth supporting.

They’re not the only ones who we support, of course, because there are many, many things that need to be supported—particularly children’s education and teaching kids to read and exposing them to the incredible experience of being able to read a book, and be transported in time and space with the subject of the book. There are many things that need supporting, and we do our best.

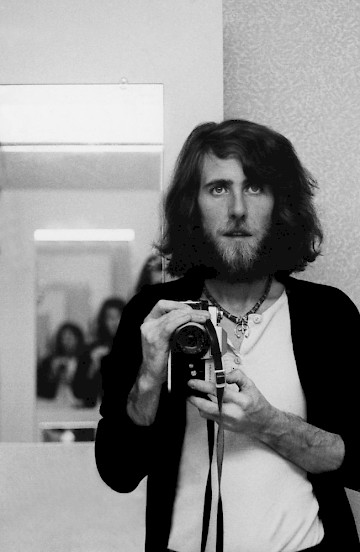

Graham Nash self-portrait, 1974You seem to have always had a latent interest in technology and advancement, such as with cameras and the inkjet printer you helped develop with Nash Editions. As someone who has had a firsthand view of the evolution of modern music recording and playback capabilities, do you find that advancement in this regard has been beneficial or detrimental to popular music?

Graham Nash self-portrait, 1974You seem to have always had a latent interest in technology and advancement, such as with cameras and the inkjet printer you helped develop with Nash Editions. As someone who has had a firsthand view of the evolution of modern music recording and playback capabilities, do you find that advancement in this regard has been beneficial or detrimental to popular music?

The closer you get to the original sound of what happened in the studio, the better, I think. It’s one of the reasons why I admire Neil for his insistence on the best sound possible—to put you closer to the plane of what went on. I think, in many cases, that the technology being developed today is an antonym. In our case, we use it in moderation.

At what point does technology stop being a facilitator and become a creative crutch?

You know, particularly for someone like me, on the road, if I have an idea at three o’clock in the morning, all I do is turn on my computer and in 25 seconds, I’m recording! It’s only two-track and it’s reasonably crude, but the main point is that I can get the idea down so that I don’t forget it.

So there are many technologies. One of the biggest problems I had with making the CSNY record was to take the nine multitrack tapes that we had recorded in different-sized halls, and different-sized stadiums, and different-sized outdoor venues, and make you believe that you were just sitting at one concert. And it was the technology—the compression technology—that helped us create that illusion; that you’re only sitting in one place.

Ultimately, though, it’s about bringing the listener closer to that performance experience as opposed glossing over imperfections.

Absolutely.

Do you think that the digitalization of music and the ubiquitous availability of music has devalued it? I asked John Mayall about this a couple weeks ago and wanted to get your take on it.

I’m not so sure that it’s devalued it, because good music is good music when all is said and done. But what happened when Napster first came on to the scene, was people started to make records that were just two great tracks, and 10 tracks of filler. And the consumer buying that finally got fed up with it and said, “I can use Napster to download just these two—the two that I want, and not have to pay for the other 10.”

Once that Pandora’s box had been opened, there was no going back. I think, in a way, it devalued it, because a lot of today’s kids expect music to be free, and they have to realize that it costs a great deal of money to be able to make a decent record.

Right. John had said that the process of going out and having to search for records led him to treasure the music on those records a bit more.

Yeah, there’s a part of me that would agree with John there.

What are you thoughts on Neil’s Pono player?

My thoughts are that, once again, Neil Young only wants the best for the listeners of his music. And you have to give it up—that’s great. The Pono player sounds fabulous—I got one of the originals, of course, as a gift from Neil. It sounds ridiculously good! God bless him for doing that! The Kickstarter response for that project was amazing. I think he raised $6 or $7 million.

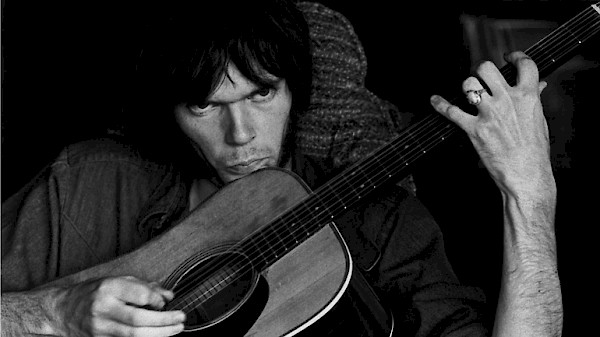

Neil Young: Photo by Graham Nash

Neil Young: Photo by Graham Nash

In your autobiography, I sensed an ongoing conflict with respect to your relationship with Neil. At first, it seemed like you were ambivalent at times about whether or not you actually considered him a friend. But the more I read, the more it seemed like—apart from David—you connected with Neil more deeply than with almost anyone else; that you find his artistic idiosyncrasies endearing, but his broader unavailability as a person disappoints you. Is that accurate?

It is. Yes, I think it’s quite accurate. And it is a little disappointing, you know, because with a true friend, there’s much to learn. And when you isolate yourself and shut yourself down from experiencing new people in life, especially people you know and love. I mean, holy Toledo, we have known each other for almost 50 years now. And to not take an opportunity like that to be a friend to a decent person, I think you’re missing out.

Right. It seemed like there were so many moments where you would really reach each other, like when he rowed you out to the middle of the lake to listen to Harvest as it was being played out of a barn. Other times, though, he would just disappear.

Well, I think, the older you get, the more things there are in your life. There’s business you have to deal with, and friends you have to deal with. And I understand—it’s like the reason why I’m not on Facebook. I hardly have time for the friends I have. I don’t need another 760 friends.

Right. So the space that comes with success can become a wedge. Gregg Allman had mentioned that in his own autobiography.

Right. And it happens to all of us.

I often write about guitar players and was pleasantly surprised to discover that you’d worked with Michael Hedges. I didn’t know that you’d been involved with him. What was the nature of that relationship?

David Crosby had turned me onto Michael Hedges. He played me a piece of music, and I said, “Well, that’s an interesting band.” And he said, “That isn’t a band.” I said, “What do you mean?” “That was one person. It was Michael Hedges and he’s playing tonight at Universal Theater in Los Angeles.”

We went down and he blew everybody away! The guy was a genius. His death was such a sad day for me. I wrote a beautiful song about him, it was called “Michael (Hedges Here).” Michael actually opened for me and David a couple times on tour, and David and I sang with him on a record. The song was called “Spring Buds.”

Recent self-portrait of Graham NashYou wrote of encountering Miles Davis during the Bitches Brew era, and you’ve spoken of an awareness of modal harmony. Also, some CSN songs, like “Dark Star,” I think, feature sections that modulate in minor thirds—a very forward thing. Did you, David, Stephen or Neil deliberately look to the harmonic or compositional elements of jazz as a creative device?

Recent self-portrait of Graham NashYou wrote of encountering Miles Davis during the Bitches Brew era, and you’ve spoken of an awareness of modal harmony. Also, some CSN songs, like “Dark Star,” I think, feature sections that modulate in minor thirds—a very forward thing. Did you, David, Stephen or Neil deliberately look to the harmonic or compositional elements of jazz as a creative device?

Absolutely. It was David Crosby. David’s main love—apart from folk music, of course, and rock and roll—is jazz. He was a great admirer of Coltrane, and saw him several times live. And his favorite piano player is McCoy Tyner. David and his son James, who plays keyboards in our band, are both jazz aficionados.

Apart from the tour, what else is on the horizon for you?

Much more music—a new record that will come out early next year, which is only six months away. A lot of painting, a lot of artistic work, and a lot of music that we’re working on. I’m a very lucky man, Nathan. My days are filled with stuff that I want to do, how lucky is that?

Absolutely. Are you doing a lot of photography at the moment?

Always, always. I have a show coming up with my friends Amy Grantham and Joel Bernstein and Elliott Landy at Woodstock in August. You know, there’s a lot of things going on in my life other than music.

In a recent interview with NPR, you said that you hoped that CSNY could reform once more because you still have “a lot of incredible music to make,” and that “younger kids are really screaming for reality.” Can CSNY still take the pulse of the public conscience and render a statement that’s going to resonate widely?

Absolutely. Because we take our own pulse, and that’s all we ever did. We don’t look at the pulse of anything except what’s going through our veins, and there is absolutely no question that CSNY are still incredibly relevant, are still viewed as a very real band with real music, and I think that it would be wonderful I could have that experience again.