Philip Graham and—from left to right—an early prototype, Myrtle and the limited-edition Dark Edwina: Photo by Sam GehrkeIn an era of impermanence—music streaming, app updates, social media—sometimes you just want to get your hands on something and not let go. At least that’s how Philip Graham felt when he made the leap and began Ear Trumpet Labs, a custom condenser microphone company in Portland.

Philip Graham and—from left to right—an early prototype, Myrtle and the limited-edition Dark Edwina: Photo by Sam GehrkeIn an era of impermanence—music streaming, app updates, social media—sometimes you just want to get your hands on something and not let go. At least that’s how Philip Graham felt when he made the leap and began Ear Trumpet Labs, a custom condenser microphone company in Portland.

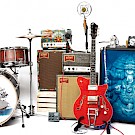

There’s no mistaking these mics—quaint, compact instruments wrapped and propped in matte-finished metals, locked in place by small springs and sturdy bolts, haloed by copper rings (or even reclaimed bicycle gears). There’s a steampunk quality about them. And it’s not just their look that’s unique, but their clarity: These condensers are often the lone sound source on stage picking up songwriters and their acoustic guitars, or even full bluegrass bands. They’ve been used by artists like Brandi Carlile, Elvis Costello, Old Crow Medicine Show, Shakey Graves, and locals including Blind Pilot, Horse Feathers and The Decemberists. Violent Femmes recorded an entire live, unplugged album in various radio stations around the country using just two Edwinas, Ear Trumpet’s signature model.

Creating microphones wasn’t a lifelong goal, or even an intention, for Graham, who’s barely a musician himself.

“I’m a really terrible guitar player,” Graham laughs. “I’m the kind of guitar player that when I first picked up an electric guitar, I was much more interested in tinkering with the amplifier and building amps than actually getting any good at playing.”

A decade ago, Graham was working in software. He’d built a career in the late ’90s in the early dot-com days, but as the years passed, he grew disinterested in the work.

“It’s so impermanent,” Graham says. “You look back and there’s almost nothing you’ve done more than five years ago that’s still being used by anybody. Actually, in software you’re kinda lucky if anything you work on ever gets used by anybody anyway. That definitely did get [tiring] after a while. I was keeping my sanity by coming back and working in my basement and just making odd stuff of one kind or another.”

Ear Trumpet Labs' Myrtle, a large-diaphragm condenser microphone with spring-suspended retro styling: Photo by Sam GehrkeHe started off with amplifiers and tubes. Eventually, he noticed his daughter, Malachi Graham, needed mics to record her solo folk project. Graham went into his basement and scraped together parts he had on hand, adding a few extras from the hardware store. The result wasn’t a crudely pieced-together Frankenstein mic, but a simple, handcrafted creation with a vintage air that became the prototype for what followed.

Ear Trumpet Labs' Myrtle, a large-diaphragm condenser microphone with spring-suspended retro styling: Photo by Sam GehrkeHe started off with amplifiers and tubes. Eventually, he noticed his daughter, Malachi Graham, needed mics to record her solo folk project. Graham went into his basement and scraped together parts he had on hand, adding a few extras from the hardware store. The result wasn’t a crudely pieced-together Frankenstein mic, but a simple, handcrafted creation with a vintage air that became the prototype for what followed.

“Nothing that you build is really coincidental, you’re always making design choices,” Graham says. “Given the stuff I had available, that maybe pushed me a little bit in a certain direction, but it’s one I’ve always been drawn to anyway.”

As Graham got going on more mics, Ear Trumpet Labs was born in 2011. The various models took on sweet monikers like Mabel and Myrtle, names collected from friends’ grandmothers. (The Louise is actually named after Graham’s own grandma.) The mics were initially built for recording, but their unique look caught the eye of musicians around Portland. Requests to use them for shows quickly followed. Those familiar with mics know that condensers are sensitive and have a reputation for being tricky in a live setting. The thing is, there aren’t a ton of options for capturing the essence of acoustic music. It became clear to Graham that there was a need.

“A lot of it is the sound guy lore: ‘Oh condensers, they’re really hard to use on stage, really feedback-y,’” Graham says. “The main problem is trying to get things heard on loud, rock-and-roll stages. Acoustic sound quality has never been prioritized. It immediately struck me, especially for acoustic musicians, this just sounds so much better. Why is everybody using dynamic mics and a stage setup that’s really evolved for rock and roll?”

Graham began shadowing live engineers around town and making feedback adjustments on the mic, then slowly handed them out for artists to try. One of the first went to the well-known old-time band Foghorn Stringband. The group took the mic on the road and people took interest in nearly every city.

“I would get a call almost every day from either the sound guy or a couple people in the audience,” Graham says. “The first year that was totally how the business got off the ground. I thought it’d be more of an uphill battle, but in mainly acoustic genres the reception was there; people have been wanting to do this, they just didn’t have the tools.”

Graham got to work, and eventually brought on a team. (His daughter Malachi is now operations manager.) Even with growth and international demand, each mic is still custom-made and hand-wired in a small space in NE Portland, supervised by the shop’s sweetest member, an Irish wolfhound named Grendel. Occasionally, Ear Trumpet brings local and touring artists in for live video sessions, while bigger names like John Oates and Patterson Hood of Drive-By Truckers simply stop by just to check things out.

Recent innovations have included Nadine, designed explicitly for the upright bass and used by Christian McBride and Foghorn’s Nadine Landry (yep, it was named for her), and a limited-edition Dark Edwina, a collaboration with dobro player Josh Swift that features a gunmetal black ceramic finish. But as Ear Trumpet Labs keeps moving forward, the inevitable question becomes what’s next? New gear? For now, Graham has his hands full with the mics.

“I think about it every now and then, and then my head hurts,” Graham laughs. “I still have my basement workbench full of a bunch of projects. I get in three or four nights every six months to work on that. The thing I always think about is how unbelievable it is, and how freaking lucky we are to work with all the artists we do. For any gear maker, it’s always super important to remember we’re just making tools for artists to make cool stuff with. Malachi and I have this mantra we try to remember: We amplify artists. That’s the goal we keep in mind.”