John Scofield is nothing less than a giant of jazz guitar. Arguably the most visible—and prolific—pillar of a pantheon buttressed by the likes of Pat Metheny, Mike Stern and Bill Frisell, Scofield’s oblique, lyrical phrasing and ceaseless experimentation have guided him to the pinnacle of achievement within the genre: stints with kingmakers Gary Burton and Miles Davis, a trio of Grammy awards, and a consistently exceptional discography as both a bandleader and sideman.

John Scofield is nothing less than a giant of jazz guitar. Arguably the most visible—and prolific—pillar of a pantheon buttressed by the likes of Pat Metheny, Mike Stern and Bill Frisell, Scofield’s oblique, lyrical phrasing and ceaseless experimentation have guided him to the pinnacle of achievement within the genre: stints with kingmakers Gary Burton and Miles Davis, a trio of Grammy awards, and a consistently exceptional discography as both a bandleader and sideman.

Since replacing Metheny in Burton’s late ’70s quartet, the signature qualities of Scofield’s vocabulary have been longstanding subjects of music press coverage and dissection by successive generations of music students. However, it is his comfort and deft facility beyond the jazz idiom that is perhaps most remarkable. While remaining eminently capable of the sophisticated modern aesthetic of Still Warm and Rough House, the 65-year-old Scofield has touched on a panoply of disparate subgenres through revolving side projects with Phil Lesh, Lettuce’s Adam Deitch and Warren Haynes of The Allman Brothers Band and Gov’t Mule. That he is able to do so without betraying the substantive fundamentals of his playing is simply another credit to his creative gift.

In interviews, Scofield often attributes the relative seamlessness of his movements between and within jazz, rock and R&B to each genre’s underlying foundation in blues. On Country For Old Men, Scofield’s Grammy-winning 2016 release, he extends this seemingly boundless lexical universality to the country-western canon—another genre he considers a constituent element of the blues diaspora. Nevertheless, each piece, whether the mellifluous consonance of “Mr. Fool” or the jagged altered harmony of “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry” becomes unmistakably his own.

Backed by his flagship rhythm section of pianist Larry Goldings, drummer Bill Stewart and bassist Steve Swallow, Scofield is scheduled to perform on Friday, January 24 at Portland’s Revolution Hall as part of the 2017 PDX Jazz Festival. In advance of this appearance, Scofield speaks to the broader creative process behind Country For Old Men and to his own country-western background, touching on the stylistic overlap of jazz and country and the virtue of learning the words to otherwise instrumental pieces. Scofield also remarks on simple, lyrical playing, naming Davis, Wayne Shorter and Paul Desmond as principal inspirations, before closing with a subtle reflection on evolution and originality in jazz.

Country For Old Men is such a neat concept. At what point did you start to envision country songs as vehicles for improvisation?

Country For Old Men is such a neat concept. At what point did you start to envision country songs as vehicles for improvisation?

From way back, I always liked classic country stuff—outlaw country and all that. I was familiar with that music and a couple years ago, I just realized that it wouldn’t be that hard to turn them into jazz tunes. It’s been very straightforward; you can just do it. Somehow, when you have a simple chord progression, it’s easy to expand on it. And that’s what we did.

I think it was really important to keep some of the character of the song, too. And we were able to do that. When I play them on the guitar, I just feel those melodies, because I’m a fan of the singers and the songs.

It sounds like you’ve got some measure of a history with country music. Can you take me through your background with it a little bit?

When I started out playing the ’60s, I wasn’t into jazz. I was just into whatever was around when I was in high school. I loved blues and rock. And there was this kind of all-embracing attitude for hippie music, you know? People liked Ravi Shankar, and they liked jazz and they liked blues. Then, there was a real awareness of country music through the folk music scene coming out of Nashville.

So, just as a guitar-head and a music-head as a kid, I liked it—and like it. I was never a complete diehard fan, or anything, but my mother’s family is from the South, even though I grew up in the North. You know, those shit-kickers on the records sort of sounded like my uncles! [Laughs]

Right. I had a lot of fun going back and digging up the original versions of some of those songs. Did you do a lot of listening leading up to the record?

Actually, all the songs on the record, except for one, were songs that I really knew. But I also did a lot of research, which is really easy to do now, as you know, through YouTube. And it was fun doing that. But, it turns out, I knew all the songs except one of the George Jones tunes—the first tune on the record, “Mr. Fool.” I’m a big George Jones fan, but I hadn’t heard that tune. The keyboard player, Larry Goldings, told me about that one.

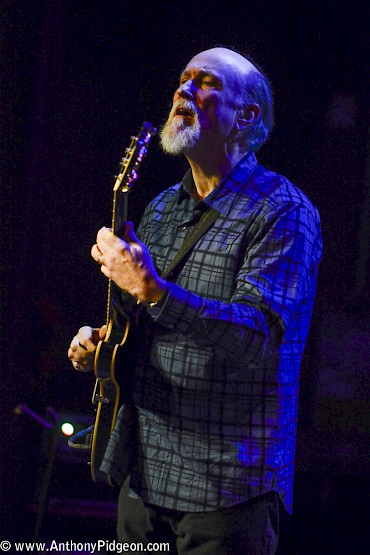

John Scofield at Revolution Hall for the PDX Jazz Festival in 2016—click to see more photos by Anthony PidgeonIn prior interviews, you’ve talked about the stylistic continuity of jazz, rock and R&B given their shared foundation in the blues. Do you see country as a similar extension of the blues?

John Scofield at Revolution Hall for the PDX Jazz Festival in 2016—click to see more photos by Anthony PidgeonIn prior interviews, you’ve talked about the stylistic continuity of jazz, rock and R&B given their shared foundation in the blues. Do you see country as a similar extension of the blues?

Yeah, yeah, I do. Especially when I play it, and when Ray Charles plays it: It’s close. It’s definitely American music. There’s a real similarity that’s closer than one would think, given the kind of political situation in America. But, first of all, black music influenced American popular music from the beginning. So, yeah, I do.

I know you’ve had longstanding musical partnerships with Larry Goldings, Bill Stewart and especially Steve Swallow. What about this material led you to want to record Country For Old Men with them?

You know, I just thought all those guys would get it, as far as us playing country tunes and doing what we did with them. I sort of knew what it would sound like before we did it. I mean, generally, I knew what we could do. And I arranged the tunes for us; for the way everybody plays.

I couldn’t have gotten just anybody. I wanted to do it with guys who were sympathetic, and I didn’t want to do it with country guys. I wanted it to be different from playing with Asleep at the Wheel, or from going to Nashville and playing with those guys. As great as they are, I wanted it to be us doing it and turning it into something else, which is jazz, basically.

In the past, you’ve said that as a guitar player, it can be a challenge to find a comfortable place in a quartet format—especially with pianists, who often use a lot of really dense, heavy voicings. Is Larry’s playing an exception? Or did you guys have to work to find a suitable balance?

Yeah, absolutely. He’s really super sensitive to whomever he’s playing with and does the right thing. And modifies his music for what’s going on around him, and has huge ears. Also, his organ playing is so great, and organ just works with guitar so well. So, on the record, he played piano and organ.

You mentioned that you went into the studio with a pretty clear idea of what you wanted the album to sound like. Was there a lot of arranging involved? Or did you come in with broader concepts for each song and let the creative process run its course?

Yeah, because I knew who was going to be on it—as far as the guys I was playing with. I’ve played with those guys as much as anybody else in the whole world. So, I did pretty much imagine how we would hit it. And that freed us, actually, to just play. I didn’t have to worry too much about, “Oh, well, I wonder if this’ll work. I wonder if that’ll work.” That’s the thing about playing with people you really know.

You can trust the music to flow on its own.

Yeah. And then there are always surprises. You want to leave the music open enough so that everybody can contribute and maybe the music will take on a little different air or shade than what you thought. And that’s actually nice.

How has this been translating to the stage? Have you guys been sticking with the same underlying concepts for each song?

Yeah, pretty much. We’re stretching out on it more and doing funny stuff to it, maybe a little meaner live. In a good way! [Laughs]

The John Scofield Trio (Scofield, BIll Stewart and Steve Swallow)Well, I’m a fan of the mean Rough House-style John Scofield. What have audiences been like?

The John Scofield Trio (Scofield, BIll Stewart and Steve Swallow)Well, I’m a fan of the mean Rough House-style John Scofield. What have audiences been like?

It’s been going over great. I have a feeling that it’s my same audience, plus a few other people who are curious. I mean, we haven’t really played a lot in the Deep South and stuff, but we’ve done the Midwest and some small towns. And those gigs have gone well because there is maybe more of an understanding of the country tunes there, I don’t know.

But it seems like it’s been going over really nicely. And I think it’s because we all love the songs, you know? We’re having so much fun playing them. We love to play, so we play the songs that we love and take it to the stratosphere and depart from the Dolly Parton world and go into our thing.

What is the song selection process like for an album like this? Were you looking for certain qualities in them, or did you simply go with tunes you liked?

I played the melodies on the guitar, and if I felt it, then that was it; that combined with whether there was a rhythmic way we could treat it. Our vocabulary works for improvising; our licks work over this shit. So, it’s not too much of a stretch.

I love the songs and I just played them on the guitar so I could sing them, literally, on the guitar. And if that felt right, then I said, “Well, can we kind of stretch out and swing it?” That was the other criterion.

Were you conscious of the lyrics of these songs?

Yes—yes. I would even write the lyrics out. It really helps me to think of the lyrics in my head when playing the song. Sometimes, all four verses have the exact same melody. I don’t have to know all the verses, but I have to know all the lyrics, you know? Or, I might mess up a couple of words in my head, but it all makes sense. [Laughs] Then it’s a song. It’s not just “da-da-da-da-da”—it’s a song. That makes the way you phrase it better on the guitar and makes it more real. So, I’m thinking of the melodies and the lyrics, yes.

There are some great excursions on the record. I would have never imagined “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry” as an improvisation of that order.

That one we completely demolished. [Laughs] It’s a really simple melody, you know? There’s like four notes in the melody or something.

Were you consciously looking for ways to stretch the song like that? Or was the arrangement something that unfolded pretty naturally?

I always knew it the Hank Williams way. I’ve known that for I don’t know how many years. The Hank Williams song is one of those songs that is part of the American tradition. It’s a huge thing—it’s not something I discovered. It’s something I think I heard my whole life.

So, I just looked at the melody and saw that it kind of worked if I did the whole melody over the E-augmented sound, which gives it this whole weird kind of weightless effect that the whole tone-augmented vibe does. I was a fan of John Coltrane, and he got really into that kind of tonality. I studied his music and his way of doing that a lot, and thought, “Wow, we could do this with ‘I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry.’” It might not please the Hank Williams fan club, but that’s cool. [Laughs] Because I love the melody, too. If we had just played on the augmented with no melody, it wouldn’t have been the same. The “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry” motif is in there at times—it comes and goes—but it’s in there, and it makes the song.

That’s such a contrast to other ones like “Mr. Fool” and “Just A Girl I Used to Know,” which are really pretty and played more straight-up. I was thinking you’d be actively looking to twist some of the songs to impart stylistic diversity.

Well, yeah—you could’ve done that with “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry,” but I wanted to do something different. I also wanted to have us play that way, and have a song that we could play like that. I wanted us to be able to do that, because that’s one of the things that we do. I didn’t want to make the whole record like those other tunes; I wanted to have that color on the album.

In a sense, songs like that seem like tests of musicianship; if someone can make an articulate, directed statement over simpler I-IV-V chord progressions.

It’s hard to play simple. It’s hard to play something that means something and that’s simple. If everybody could do it, they would. A lot of people study their whole lives to play complicated music, and they need to do that because they can’t play simply.

I guess we all have our strong points, but I’ve always liked songs.

Have you always recognized playing simply as one of your own strong points?

No, actually. I think I really started to concentrate on it later. I’d already been out there for a while. Even though I liked it, I was pretty busy trying to learn how to play complicated, which takes a lot of work! Then, after I got a little more of that under my belt, what I really liked were the jazz players that were able to, at times, play very lyrically. Not all the time; it’s just a color that you want to have together to use in tandem with some thorny shit like we got into on “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry.”

You know, when you’re first learning how to play, you get obsessed with playing fast and learning how to play long lines, and then later on, it’s like, “Well, that’s great.” But I’d listen to the players I love, like Miles Davis and Wayne Shorter and these great improvisers, and they’d mix it up.

Would you consider Paul Desmond a player like that?

I love Paul Desmond, yeah. He’s one of the greats, and he’s actually overlooked sometimes. He’s as good as it gets; those records he made with Jim Hall are fantastic.

You’re often asked about the construction of your own language as a musician, but I’m curious about your thoughts on appropriating other musical dialects. You play in so many contexts beyond jazz, I feel like some of that has been necessary.

Well, first of all, I don’t quite feel—I mean, I take a little bit from country, and a little bit from blues, and I play jazz. But I’m not the only guy who does that. I mean, you can hear country sounds all over jazz; in Ornette Coleman and in Sonny Rollins, just in their phrases. And in melodies, you’ll hear people quote “Battle Hymn of the Republic” or “Dixie” in jazz.

So, the way I got to a lot of this stuff is really through jazz and with all the other music that’s around. I see folk music as related to jazz, I see pop music as related to jazz, and I see the blues as related to jazz. I think, as far as getting your own vocabulary, it’s just learning how to play music, and the stuff that you like will [come through].

Everything has already been played, right? As a music fan, I just go out and listen and try and find the melodies and the phrases and the sound and the feel that are already out there. It’s already out there! [It’s like] the thing that’s cool about human beings. It’s like language. You don’t invent the English language and write a book. You just use music to make your statement, and it comes out a little bit different because we’re individuals.

Would you argue that the adaptation of other dialects throughout a musician’s progression is essential? In his autobiography, Miles Davis talked about the existential threat posed by making a figurative museum piece out of a given style of music, effectively ending its relevance as art.

You know, I just keep trying to do something that feels fresh; that’s a little different than what I always do. On my own, I just sit around and play standards and jazz like everybody else—I’m a big jazz fan. [Laughs]

But I keep thinking that there’s got to be a little different angle, if it’s even worth putting out, because the jazz thing has been done so well already. So, I just keep looking for different ways to frame it.