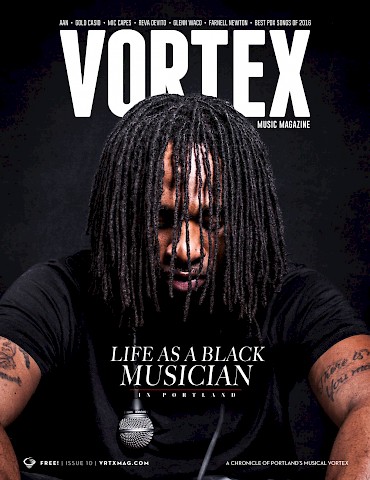

"When they signed the Bill of Rights, I was considered to be three-fifths of a human being. So, the other two-fifths, I guess I’m from outer space or something." —Portland hip-hop artist Rasheed Jamal

"When they signed the Bill of Rights, I was considered to be three-fifths of a human being. So, the other two-fifths, I guess I’m from outer space or something." —Portland hip-hop artist Rasheed Jamal

Fact: Portland is the whitest major city in the United States.

Fact: Oregon has a racist history.

Fact: The two are connected and there are lasting effects.

Here’s something that white Portland needs to understand about the black mentality. Put yourself in their shoes. Years of mistreatment have led to mistrust, which has altered the psyches and worldview of people of color—even in utopian Portland.

It is important to educate ourselves and children about the realities our past has created for people of traditionally marginalized and disenfranchised populations, namely people of color.

Hip-hop artist Rasheed Jamal moved to our city in 2008. He moved from Arkansas, which “has the highest concentration per capita of hate groups,” he tells me. He moved to get out of the South. With a brother already here, Portland was an easy landing pad. Yet, that doesn’t mean living in Portland is easy for a black man.

“You leave the house, you don’t know how you’re going to come back home. We all do that,” Jamal says. “We just hope that it goes the way it went yesterday. But when it gets to the point where you’ve dealt with so much trauma, that you’re just at the point where you want to snap…” he trails off.

I’m a white Portlander, born and raised. I don’t worry about how I’m going to get home at the end of the day. I’m not really sure that I’ve ever had to worry about that living in this city. His revelation and honesty bursts my bubble. And he’s not the only one who feels like this.

“At the end of the day, who doesn’t want to go home? Nobody wants to get shot. Nobody wants to be fighting. Nobody wants to make the national news,” describes StarChile, a veteran concert promoter and hip-hop scene mainstay who’s been active some 15 years.

StarChile: Photo by Miss Lopez MediaStarChile is also the man who realized the importance of building bridges after hostility between the city, police and fire marshals came to a head back in 2014. Apparent racial profiling, club closures of hip-hop hot spots, all of “it cast a negative light on the idea of a liberal and diverse Portland,” Jamal says. “It shed light on certain situations that had long been ignored.”

StarChile: Photo by Miss Lopez MediaStarChile is also the man who realized the importance of building bridges after hostility between the city, police and fire marshals came to a head back in 2014. Apparent racial profiling, club closures of hip-hop hot spots, all of “it cast a negative light on the idea of a liberal and diverse Portland,” Jamal says. “It shed light on certain situations that had long been ignored.”

“The sense of culture and diversity that Portland likes to pat itself on the back for having, it’s not there,” Jamal states. “When they signed the Bill of Rights, I was considered to be three-fifths of a human being. So, the other two-fifths, I guess I’m from outer space or something.”

It’s no easy task for a person of color to approach their oppressor. “I don’t feel like those who are being slighted should have to go to the people who are slighting you,” StarChile explains. “If you’re the one messing up, then you need to come make this right. Or at least meet me in the middle.”

StarChile did step up and make the meeting happen, opening up a dialogue between the black hip-hop community and police. “And we’ve had great conversations. I’ve been wrong, I’ve apologized. They’ve been wrong, they’ve apologized. I’ve seen the difference in their actions,” he tells.

It’s actually become his personal mission to open the communication floodgates. “I want to have conversations with more police officers so they can see somebody that looks like me, that’s my color, talking to them articulately,” he says. Working as an intermediary, StarChile can accurately and deliberately tell officers how their actions are perceived by his community. He can clarify misinformation, de-escalate situations, and most importantly, try to avoid mob mentality because, as the refrain goes, “Fuck tha police.”

“Don’t nobody wanna hear that,” he says. “Nothing’s gonna come of that. But if I look you in your face and say, ‘This is why you need to stop doing this.’” Then, change will happen—and it has.

Growing Diversity?

Between the summer of 2014 and 2015, the Portland metropolitan area grew by 111 people per day, according to Census Bureau estimates. And since that growth shows no signs of slowing down, the influx of people absolutely puts strains on the city’s infrastructure and culture.

Here’s a nice theory: At 76 percent white, people moving to Portland from other major cities are coming from places that are more diverse, which means they’re bringing their own histories and backgrounds of being raised or having lived in a place that is inherently more diverse than our city.

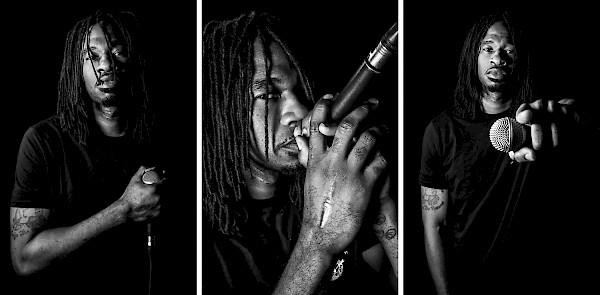

Rasheed JamalIt’s a questionable theory, though, one that StarChile counters by saying, “I don’t know if there’s ever been a TV show that has done more damage to a city in the history of man,” he pauses to laugh, “than fucking Portlandia. Because in concept you’re right: People come from places of greater diversity, but when you look at the kind of people that are moving here, it’s like they saw that shit and were like, ‘Yo! We got a safe haven! Let’s go!’”

Rasheed JamalIt’s a questionable theory, though, one that StarChile counters by saying, “I don’t know if there’s ever been a TV show that has done more damage to a city in the history of man,” he pauses to laugh, “than fucking Portlandia. Because in concept you’re right: People come from places of greater diversity, but when you look at the kind of people that are moving here, it’s like they saw that shit and were like, ‘Yo! We got a safe haven! Let’s go!’”

Jamal also debunks the artistic-hipster-bum stereotype popularized by the show: “A few years ago, this was the place to retire at 20. And now, your ass better have a job or you ain’t got nowhere to live.”

Yet, it’s also simple economics: More people can amplify what’s happening here locally and what the local market can sustain. When people complain of new residents flooding the city, StarChile thinks, “Good.” It’s an opportunity. “If I could only control the kind of people that moved here… that’d be even better,” he jokes.

Growing Success

Nicholas Harris, the co-founder of Soul’d Out Productions, started bringing talent who perform world, reggae, jazz, funk, hip-hop and electronic music—often by made by black musicians or rooted in their musical traditions—to the city in 2008. Working in tandem with Double Tee Concerts and the Roseland Theater, he also throws the annual, citywide Soul’d Out Music Festival, which is full of diverse bookings.

“When we first started producing shows in Portland, it was clear we were the outlier,” Harris says. “Folk, Americana, indie rock were king and it was a serious struggle getting established. Clearly things have shifted.” The coming generation appears to have “a broader musical palate than the generation before them, a new wave of national and local artists [are] producing quality music with real depth, [and] new groups of people [are] coming to PDX from more diverse parts of the country and subsequently bringing their more diverse tastes with them.”

Attendance at these events is up, but more importantly, outsider attitudes about Portland have changed. “Maybe the biggest signifier, at least nationally, are the responses we get from our colleagues in New Orleans and Washington D.C. and the artists themselves that we bring to town,” Harris explains. “Whereas we used to get asked, ‘You’re bringing what kind of music to Portland, Ore.?!’ Or, ‘You want us to perform where?!’ Now we hear more and more that these artists actually have Portland on their radar as a destination city, or other promoters in other markets seeing that we can actually sustain, let alone succeed, by producing events that historically have not done well here due to the demographic realities.”

While Portland may only be 7 percent black, there’s still a thirst for the true American art forms that our country’s black culture has produced. Jamal, StarChile and XRAY.fm’s DJ Klyph all believe work remains in the local scene, citing a lack of venues available to hip-hop acts, especially those that can accommodate all ages.

Rasheed Jamal—listen to his new track “Love Is The Highest Religion” below, about which he says: "At this point, I just want to be free to express my thoughts, emotions and feelings just like anybody and not be attached to the labels that only serve as limitations."Under 21ers are “probably the most underserved community here when it comes to the music business,” Jamal says. “There’s no venue and there’s no stage for there to be all-ages [hip-hop] shows, because they feel like all-ages shows translate into black kids don’t know how to act and somebody gonna start a fight and somebody’s gonna do this and somebody’s gonna do that. And I feel like that’s the reason that it doesn’t happen, even though we don’t carry ourselves with that energy for that type of thing to happen.”

Rasheed Jamal—listen to his new track “Love Is The Highest Religion” below, about which he says: "At this point, I just want to be free to express my thoughts, emotions and feelings just like anybody and not be attached to the labels that only serve as limitations."Under 21ers are “probably the most underserved community here when it comes to the music business,” Jamal says. “There’s no venue and there’s no stage for there to be all-ages [hip-hop] shows, because they feel like all-ages shows translate into black kids don’t know how to act and somebody gonna start a fight and somebody’s gonna do this and somebody’s gonna do that. And I feel like that’s the reason that it doesn’t happen, even though we don’t carry ourselves with that energy for that type of thing to happen.”

Read more about the struggles of the underground, all-ages scene.

Traditional places of gathering for black communities have been pushed out of gentrifying neighborhoods, as have the residents themselves. “As individuals and businesses move into the area with the finances to purchase properties but then choose to renovate or convert these properties into businesses other than performance spaces, it limits the opportunities for artists to share their gifts, grow their crafts, and contribute to the local scene,” DJ Klyph explains.

In light of this, DJ Klyph and StarChile have found new partners in established music scene businesses, like McMenamins. StarChile now hosts two monthly showcases that highlight primarily black music: the hip-hop-focused Mic Check every last Thursday at the White Eagle (co-curated by Klyph) and Soul Clap every second Friday at the Mission Theater (co-hosted by DJ O.G. One). Good Cheer Records co-founder Blake Hickman and Mac Smiff, the editor of We Out Here Magazine (Portland’s online hip-hop lifestyle publication), have also spent the last two years building a first Thursday showcase of local hip-hop at Kelly’s Olympian. The Thesis (which Vortex is proud to also co-sponsor) sells out every month.

Coming Together

“The demand for shows is higher now,” says underground organizer Mia O’Connor-Smith, who’s responsible for curating Deep Underground events that elevate black and brown artists. “There are more venues to play at, but these venues are either very difficult to work with or don’t know how to engage with audiences of color.”

In the last few years, “the Portland hip-hop scene has really come together as a community,” describes photographer Renée Lopez of Miss Lopez Media. “We aren’t taking no for an answer and we are doing things that I haven’t seen done in this city before.”

Photo by Miss Lopez MediaStill, long-held biases and racism are present in our society—and city. This past March, Portland Public Schools officially banned “rap music” on school buses. A directive from PPS’ senior director of transportation prescribed approved radio stations, permitting only the genres of pop, country and jazz (with no mention of Latin music). When the ban came to the public’s attention this summer, the district backtracked and decided to revise its music guidelines.

Photo by Miss Lopez MediaStill, long-held biases and racism are present in our society—and city. This past March, Portland Public Schools officially banned “rap music” on school buses. A directive from PPS’ senior director of transportation prescribed approved radio stations, permitting only the genres of pop, country and jazz (with no mention of Latin music). When the ban came to the public’s attention this summer, the district backtracked and decided to revise its music guidelines.

Jamal calls racism a disease. “It’s fear. Not understanding. And not wanting to understand. And not understanding that you don’t want to understand. And not understanding that your lives are so far from our reality.”

“As a black man, you want to have the kumbaya story but this shit’s just not real,” StarChile says. “I don’t need to look to the 1800s to get mad at something that white people did. Y’all give us something every month.”

Click here to read more stories from the current issue!But he can continue to focus on creating change in today’s society, putting himself in others’ shoes and asking them to do the same. “I just want to be looked at the same way you look at your child, or your brother, or your cousin. Don’t look at me like, ‘Oh, that’s a black dude.’ ‘No, that’s another person, who just happens to be a different color than I do. They have the same issues and worries that I do.’”

Click here to read more stories from the current issue!But he can continue to focus on creating change in today’s society, putting himself in others’ shoes and asking them to do the same. “I just want to be looked at the same way you look at your child, or your brother, or your cousin. Don’t look at me like, ‘Oh, that’s a black dude.’ ‘No, that’s another person, who just happens to be a different color than I do. They have the same issues and worries that I do.’”

Understanding and uniting is key to resolution, and hopefully change. “There are definitely so many white people who have done so much that’s helped us and have fought side by side with us,” StarChile says. “History in this country has shown us: Don’t shit get done without y’all.”

“When the tide rises—and in our case, rises quickly—you either have to have your boat already in the water, a life preserver close at hand, or you get washed away,” Harris explains. “If you don’t have your own boat in the water already—and so few of us generally do—what are the ways we can band together to ensure our pockets of community don’t get washed away as well? How do we use our most important vote—the almighty dollar—to support the businesses, artists and government officials we really want to see succeed? In these times, it seems clear that our choice is to either take over the ship and correct its course to the benefit of our communities, or we just let it sink. We continue to pursue the former over the latter through music, art and creativity, and welcome all willing partners committed to the struggle.”

How To Strengthen Your Arts Community

Left to right: Mia O’Connor-Smith, Renée Lopez, StarChile and DJ Klyph“Build together. Anything you want to do, you can start together with other amazing people of color, so you can have things the way you want without feeling like you have to compromise your vision.” —Renée Lopez

Left to right: Mia O’Connor-Smith, Renée Lopez, StarChile and DJ Klyph“Build together. Anything you want to do, you can start together with other amazing people of color, so you can have things the way you want without feeling like you have to compromise your vision.” —Renée Lopez

“Be consistent with what you do and understand the impact of what you do on the greater community. Consider what may first appear as an obstacle could truly be an opportunity. Pause before you react, be sure you have all the information, then find like-minded individuals on the journey to grow this Northwest movement.” —DJ Klyph

“Learn a lot from folks who are older and more experienced in the music world and [be] excited to really make action out of that [advice].” —Mia O’Connor-Smith

“Be professional at all costs. Meet as many people as possible. Talk to people. If you have a problem with somebody, find them. Confront them, peacefully. Talk to them. I would urge people to have genuine conversations with those you feel are wronging you. But you have to go in being prepared to possibly be wrong. And both sides have to be willing to make progress.” —StarChile