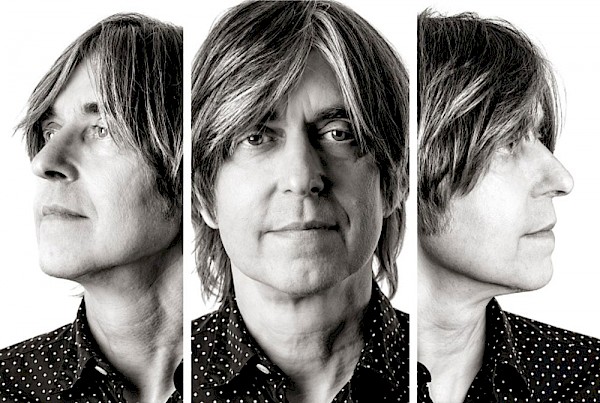

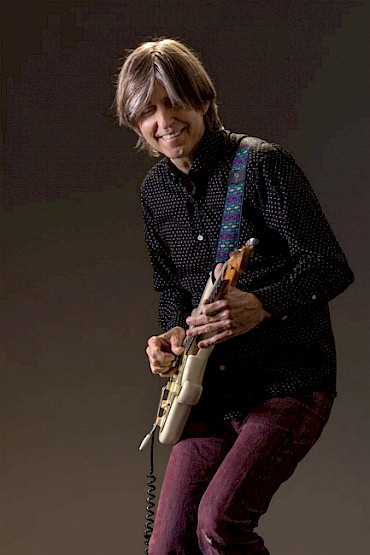

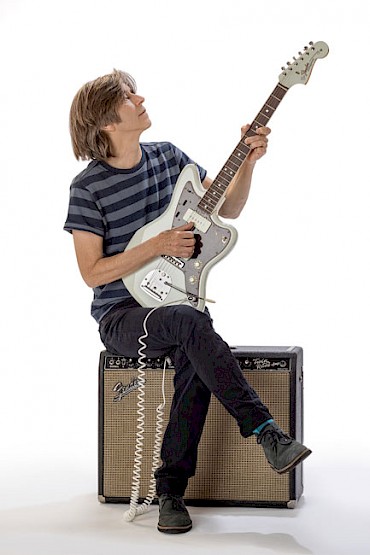

Eric Johnson's 'Collage' cover art: Photo by Max Crace2018 is shaping up to be a good year for Eric Johnson.

Eric Johnson's 'Collage' cover art: Photo by Max Crace2018 is shaping up to be a good year for Eric Johnson.

Barely three months removed from the release of Collage, his 10th studio effort, Johnson—the Austin, Texas, guitar legend—is already setting his sights elsewhere: a nationwide tour celebrating Ah Via Musicom, an archetypal rock guitar record widely considered a touchstone of its genre.

Upon its 1990 release, Ah Via Musicom propelled Johnson to international renown, yielding a trio of top 10 hits—“Cliffs of Dover,” “Righteous” and “Trademark”—and a Grammy Award for Best Instrumental Rock Performance. It would go on to be certified platinum in 2003, having sold in excess of one million copies.

“Cliffs of Dover” has enjoyed a particularly enduring appeal. Its soaring melody lines and signature introduction, a bursting free-time cadenza of descending pentatonic runs and oblique motion figures, are instantly recognizable and have made Johnson a fixture of guitar magazine covers and best-of polls, as did his sound, a rich, singing tenor that became the object of concerted speculation among contemporary musicians.

The success of Ah Via Musicom bestowed mixed blessings, however. Seeking to broaden his creative scope, Johnson felt limited by the guitar hero identity—and perhaps as much by the heft of his own expectations. An exacting studio clinician, Johnson also labored under pressure to exceed the standard of Ah Via Musicom, requiring nearly six years to release a follow up, 1996’s Venus Isle. He would then largely retreat from full-scale recording projects, opting instead to issue a live album and a patchwork of previously unreleased tracks, until Bloom arrived nearly a decade later.

Photo by Max CraceBut the relative wilderness years of the mid-'90s and early aughts seem to have been creatively purifying for Johnson. In a cycle beginning with 2010’s Up Close, Johnson has issued records nearly every two years, each seeming to highlight separate facets of his talent—the songwriting, acoustic fingerstyle and piano playing—once barred from expression. He ventured into fusion with jazz guitar totem Mike Stern on 2014’s Eclectic, trading lines with one of the discipline’s most formidable and complete talents. At 63, Johnson now appears vivified, and perhaps more himself than he ever has.

Photo by Max CraceBut the relative wilderness years of the mid-'90s and early aughts seem to have been creatively purifying for Johnson. In a cycle beginning with 2010’s Up Close, Johnson has issued records nearly every two years, each seeming to highlight separate facets of his talent—the songwriting, acoustic fingerstyle and piano playing—once barred from expression. He ventured into fusion with jazz guitar totem Mike Stern on 2014’s Eclectic, trading lines with one of the discipline’s most formidable and complete talents. At 63, Johnson now appears vivified, and perhaps more himself than he ever has.

On Collage, Johnson inches ever closer to his own self-realization. Largely cut live in his Austin studio facility, the album’s loose feel is a welcome novelty. The ethereal minor ii-vs and solo phrasing of “To Love You” come across as Johnson’s adoption of a Stern hallmark, while “Morning Sun” sees him playing with a similarly newfound verve. Covers of Jimi Hendrix’s “One Rainy Wish”—arranged for solo acoustic guitar—and “Pipeline,” The Chantays surf-rock classic, are likely there for no reason other than that Johnson simply enjoys playing them.

For listeners, the concurrency of Johnson’s new release and the Ah Via Musicom tour are a rare gift, a sweeping career retrospective from both poles. With hope, they may also find newfound appreciation for the hidden gems of Johnson’s 1990 opus: the spiritual, volcanic majesty of Johnson’s solos on “Desert Rose,” the Ted Greene-inspired chord chemistry of “Forty Mile Town,” and “Trademark”'s undulating 12/8 rhythm.

And for Johnson, long one of rock’s singular talents, the new year’s trappings should finally affirm for him what was so special nearly 30 years ago.

I thought it would be fun to start by discussing Collage. Is there anything about it you haven’t had an opportunity to speak to yet?

You know, it was really just more of a record to do for fun, and where I cut as much live stuff as possible. Because it’s an ongoing template of me wanting to try to record a full piece of music— whether I go back or overdub—and try to paint a bigger picture.

With that in mind, I just went, “Well, I’ve got a few original things and let’s do these other people’s songs just for fun and rearrange them.” So, it was more like, less pressure, less stress; let’s just have a little more fun and kind of change the way I go about recording.

And that was the premise of what I was doing. It just happened that those were the songs that I kind of chose or had available. I don’t know if it’s the most connective or the most epic song record I’ve ever made, but it shows promise of a little bit more energy and vibe, and just performing.

I want to pursue that direction a little more.

“To Love You” reminded me of something off of Upside Downside or one of Mike Stern’s early records. Has your time with him rubbed off on you much?

I think so. I mean, we did three tours together and we made a record together. Definitely. He’s such a powerful player that it’s natural that something’s going to rub off on me. And he’s such a musicologist; he’s such a deep player. He can play anything.

Photo by Max CraceWould you guys sit down and work on things? Would you ever come to him with a question about something he did?

Photo by Max CraceWould you guys sit down and work on things? Would you ever come to him with a question about something he did?

Yeah. I mean, usually we were so busy writing material and working on stuff. We’d just sit down and jam but we didn’t get into too much straight-on. But a little bit of that. He’d want to know some weird thing I did. And, of course, I’d ask him a bunch of questions about all of his harmonic theory and stuff.

Something else that stands out—and has always stood out—is your facility with chords: the wide intervals and extensions. What does that go back to?

Obviously, Chord Chemistry by Ted Greene, and also just studying piano players.

If you study piano players, then you’ll open up your limitations as to how you approach chords. I think, a lot of times, chords on guitar are boxed into what’s so readily available on the fretboard. But if you listen to some piano voicings, they’re more wide open, and renditions of those can be done on guitar.

And that’s what’s so cool about Ted Greene. I mean, he was all over that. To me, I like that kind of chordal work. Maybe a little more than just playing the standard voicings that you would on the guitar.

Because I think that there are some voicings that are your expected go-to voicings on guitar. Which, if you had a choice, you’d probably go, “Well, I’m going to voice it differently, because it’s not the best voicing that I might think of.” You know what I mean?

There are some possibilities—maybe not as many as on a piano—but surely there are some possibilities that can get you out of that boxed-in thing.

When did that start coming into your playing? I started going back through your older work from the late '70s and early '80s to try and pinpoint it.

Photo by Max CraceI suppose I started in the Electromagnets, but it was kind of a gradual process. And then, Jimi Hendrix was really good at that, too. He did that in pop music before anybody did.

Photo by Max CraceI suppose I started in the Electromagnets, but it was kind of a gradual process. And then, Jimi Hendrix was really good at that, too. He did that in pop music before anybody did.

What keeps more people from exploring that facet of the instrument?

I guess it’s what the purpose or the function of the guitar is for you. Like, thank god The Beatles didn’t do that, because those stock voicings are what made the songs perfect.

But then you take somebody else and that wouldn’t be true. Like, Johnny Smith, you know? You wouldn’t want to hear him play those stock voicings. So, it really has to do with the function and the application and the mood of what you’re trying to create. Where’s the emphasis?

To me, where you run into a little bit of hot water, is if you use stock voicings and then you have a stock melody and a stock song that’s really kind of innocuous or generic, and you have this whole generic thing happening. You don’t really have any flair or weight anywhere. You know what I mean? It’s really kind of about how all the pieces fit together.

Right.

And that’s what I think is so beautiful about it. You can play those stock voicings and they’re awesome. If you could just free yourself from being, “Oh, no, it’s only Keith Jarrett’s voicings that we can deal with, and these other people don’t know.” Well, thank god they don’t know! [Laughs] Thank god that Ringo couldn’t play like Eric Gravatt, because Eric Gravatt could never play like Ringo, dude, you know?

If you look at the agenda and what is supposed to be happening, all of a sudden you free yourself to see this amazing beauty in whatever it is.

Still, it surprises me that, for all the advancement on the guitar, you only really hear jazz players doing it. It’s not a thing in rock.

Well, you know, it’s interesting you say that. I don’t know what happened, but the rock guitar thing—and it’s disheartening to me when I think about it—but it kind of went off on a strange tangent. I mean, you had this rock guitar thing with Hendrix and [Jeff] Beck, and “Happenings Ten Years Time Ago” with the feedback and Hendrix with “Third Stone [from the Sun].”

And you were kind of touching on it, this incredible musicality of voicings and depth.

Then, we got off onto where it became like a video game with shredding and who’s-the-fastest-guy on-the-block? I mean, I’m sure a lot of people would argue with me, and, I guess, it depends on what you term “musicality.” Somebody [might] argue that I don’t know what I’m talking about; which, in a way, they’re right about. [Laughs]

That might be an uphill battle.

But, to me, something got lost in translation. And quite honestly, the proof is in the pudding. No wonder kids have lost interest in guitar, and especially in somebody coming out and playing 20-minute guitar solos. It’s just been—it’s become a caricature, really. And you can’t say “Third Stone” or “May This Be Love” or some of the chordal work on Axis[: Bold as Love] is a caricature.

To me, it’s everything but a caricature.

At the time Ah Via Musicom came out, would you have ever considered putting a song like “Pipeline” on an album?

You know, we talked about it over the years, but it was more for fun. It’s not so important that every single song I do be my own song anymore. I just enjoy playing music, and sometimes I have a lot of fun taking another song and rearranging it.

Is music more fun for you now?

Yeah! I think that after the Musicom thing, I got a little too serious about, “Oh, everything has to be really great.” Well, yeah it does, but what is “great”? Sometimes you luck out and end up creating something great, but sometimes it ends up being great without being any good at all. I think that as I get older, I look back at some of my most fun times, and it’s before any agenda or gravity or anything. You’re just playing for fun.

At the same time, I want to put as much musicality and growth in it as I can. But, I don’t want it to sound like I’m doing it. I don’t want it to feel awkward like that. Like, if you listen to “Eleanor Rigby” and you hear that octet that George Martin scored. I mean, it’s so hip! You’re just listening to a beautiful piece of music. If you listen to Duke Ellington, you can tell it’s really tight and arranged, but it’s all in service and support of the music.

I don’t think there’s anything wrong with trying to push the envelope or the high-water mark of musicality. But, where it really becomes not only unimportant, but actually detrimental, is when it takes over the service of the song or the music.

What about your processes hasn’t changed?

Well, the way I’m going to go about trying to do my best is starting to change. It’s going to be more about trying to raise the bar on my musical ability to where I can do a better job of performing live. I realize I’ve made a lot of records where I pieced them together note by note. And I think a lot of them sound that way. They might end up being just right, but I just went, “You know what? There’s something missing.”

You hear it in all the autotuned country music. And I don’t mean to be harping about modern music, because there’s a lot of great music. I just think that what it did to me was create a personal epiphany; that something’s missing. I just felt a hollowness.

You know, you put on those late-'50s Ray Charles records and just listen to the vibe, whether you like the music or not. Just the vibe—it doesn’t get any better than that. It’s actual humans reaching out to actual humans with this vibe.

It’s soul!

It’s soul!

Yeah, yeah! I just realized that, in my opinion, I would do very well to have—or to try, at least—to inculcate a lot more of that in what I do. So, that’s what I would like to think about more and entertain more.

As an artist, how do you approach change without losing sight of your own identity and values?

I think the most artistic thing you can do is to stay liquid. Like, if you have a little bit of success at something, there’s always kind of a tendency to gel what you think you are. All of a sudden, you start living in this kind of shell a little bit. You’ve encased yourself. I think the best thing you can do is to stay liquid and keep growing.

We will always be a student of what we do. There’s always something to learn and there’s always something we missed. The minute we decide we’ve completed the alphabet, we’ve kind of gelled ourselves and we’re not liquid anymore, you know?

Right.

You also have a responsibility to be honest with yourself. I remember a time after I made a certain record, where it was selling so much, I went, “Well, I’m alright. I’m here. Where’s the lawn chair? I’m here and I’ll stay here.” It’s really not that way. You have a responsibility to keep coming up with something awesome. Like, a writer’s got to come up with another book that’s really captivating and riveting, to where he warrants his progression forward and keeping his audience. You can’t just arrive and go, “Okay, I’ve got it now and I’ll just spew out this and that,” and expect everybody to stay at the same level.

So, I think it’s just always staying a student, staying liquid and staying in touch with your passion and what really excites you and gives you joy, so you can infectiously pass that on to your listeners or your readers.