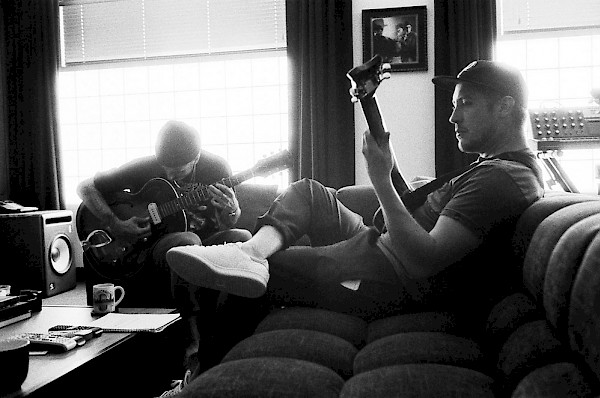

Original Lords: Childhood friends John Gourley and Zach Carothers started Portugal. The Man in 2004

Original Lords: Childhood friends John Gourley and Zach Carothers started Portugal. The Man in 2004

Portugal. The Man’s Courage, Playfulness and Best Album Yet

The success of Portland-based psych pop rockers Portugal. The Man is hardly just cup-runneth-over talent. The band’s released a dozen EPs and LPs dating back to 2005, all on top of an oft-hectic tour schedule.

The group’s last effort—the 2013 Danger Mouse-produced, Atlantic Records debut Evil Friends—did not disappoint artistically or commercially, hitting #28 on the Billboard 200. But the guys got lost in a thicket during work on follow-up Gloomin + Doomin, says lead singer and songwriter John Gourley. Ironically, it may have all been due to the band’s own prolific recording abilities, which led them to start tons of songs they never finished. It was as if they began building a new house, bigger than any previous, but never thought to leave a doorway.

“So we’re going along, working on Gloomin + Doomin, and we’re thinking about it like, ‘Oh, this is an important record,’” Gourley says. “Everything we’ve done, it’s important for us. [But] you get caught up in your own game and... you start to think about all these stories you’ve heard, about having like a hundred [unfinished] songs.”

It took a trip back to his hometown of Wasilla, Alaska, before Gourley recognized that what worked for Prince, Elvis Costello or Paul Simon might not be right for Portugal. The Man.

It took a trip back to his hometown of Wasilla, Alaska, before Gourley recognized that what worked for Prince, Elvis Costello or Paul Simon might not be right for Portugal. The Man.

“You learn something every time you go into the studio,” he says. “The thing I learned about this band is to ask the question right at the beginning: How many songs do we want to write and record and put out on this album? Because you only really need that many. Nobody should be recording a hundred ideas, and laying them down like they’re good.”

Back in Wasilla, there was a “tough love” conversation with his dad, who asked why things were taking so long, and the moment Gourley found his dad’s ticket stub from the original 1969 Woodstock music festival.

Gourley and PTM ultimately made one of the most courageous, difficult decisions any artist can make: They threw out three years of work and started from scratch—with “new, full-on, musical boners,” as the group’s online bio jokes.

Hard at work: Carothers and GourleyTheir new album? It’s called Woodstock. The early single “Feel It Still” suggests Gourley’s not exaggerating when he says this one’s special.

Hard at work: Carothers and GourleyTheir new album? It’s called Woodstock. The early single “Feel It Still” suggests Gourley’s not exaggerating when he says this one’s special.

“I feel like we made an album that sounds like a classic 2000 CD binder,” Gourley notes. “It’s our best record, and I look at that in many different ways. It feels really good.”

It’s not unprecedented for a major label artist to chuck a whole album, but was PTM given a longer rope? The label won’t discuss it. An Atlantic Records spokesperson described it as “fairly unusual, not something I’ve ever run into before.” Meanwhile, the band’s website jokes, “there was the constant threat that the band’s record label might have them killed.”

The changin’ times also had something to do with PTM’s reboot to a more politically charged aesthetic, Gourley says.

“A lot of this record came about watching the way Trump uses Twitter,” he explains. “We were watching [the election] go down, like, ‘Man, this dude is so good at deflecting and just shutting this down, and stringing along the most fucked up, racist groups of people.’”

John Gourley on top of the worldThe way the Alaska-born, Stumptown-adopted Gourley talks, being a Northwesterner, or Portlander, is about being fiercely organic: a lust for life and nature, buying local, rejecting artifice.

John Gourley on top of the worldThe way the Alaska-born, Stumptown-adopted Gourley talks, being a Northwesterner, or Portlander, is about being fiercely organic: a lust for life and nature, buying local, rejecting artifice.

Gourley speaks softly and laughs frequently. In a place and at a moment where many an artist would be cagey, he’s open—even transparent. He sports a hipster mustache with its own Instagram page but denies it holds special powers. “That facial hair will not get you anywhere in Portland if you don’t have something behind it,” he laughs. “The power is in the mind: I know where I’m at, I know what I do.”

The twin currents that charge Gourley, and PTM, are reminiscent of those that have marked many a great artist:

Play. Work.

On the one hand, there’s child mind, humor, a melody that shimmers and dances, like Gourley’s own pitch-perfect falsetto. It may come from his five-year-old daughter, drunken antics with bandmates, his unique visual art.

Gotta get up to get downIt’s in the group’s Twitter feed, dubbed Lords of Portland, and the video for late-2016 single “Noise Pollution,” which features Gourley doing pushups in an icy Alaskan river, perched 40 feet up a birch tree, and driving a magical, winking Pontiac Fiero (watch below).

Gotta get up to get downIt’s in the group’s Twitter feed, dubbed Lords of Portland, and the video for late-2016 single “Noise Pollution,” which features Gourley doing pushups in an icy Alaskan river, perched 40 feet up a birch tree, and driving a magical, winking Pontiac Fiero (watch below).

“That is the way I live my life—jump in the mud,” Gourley says. “You can’t be scared of fucking this thing up.”

On the other hand, Gourley, like the band, has a work ethic you ain’t got time to fuck with. He’s highly competitive. He respects and understands the sacrifices needed to succeed at this level of the industry.

“It’s so important to me to step on to the field, point to left field, and hit a home run,” Gourley explains. “There has to be a competitive edge. You got to want it more than the next guy.”

There are compromises, the 35-year-old admits.

Though the pushups were “the coldest I think I’ve ever been in my life,” Gourley didn’t actually climb that tree—he was placed there by a forklift. But it’s still badass.

“I was just so wrecked,” he laughs. “The insides of my thighs were so bruised.”

So, just how socially conscious is Woodstock? The album’s countercultural vibe reflects the progressive politics of the city of Portland itself.

An interactive video for “Feel It Still” was produced by Wieden+Kennedy and features local rapper The Last Artful, Dodgr, who Gourley calls a “true Lord of Portland.” It allows viewers to click icons to make contributions to the ACLU, climate change, and undocumented or indigenous groups. (Watch the video at the end of this article.)

The video’s press release mentions #theresistance. But just as the key lyric, “I’m a rebel just for kicks, now,” is double sided, Gourley says he can’t do overtly political stuff. Racial and gender equality or clean water are just human—common sense.

“I don’t think of these as political issues,” Gourley says. “At the end of the day, we’re all just people.”

“We have to discuss this stuff, we’re losing sight of what America is. And we’re a patriotic band, man. The thing that drives me crazy is when you hear these comments: ‘You’re a musician—stick to music.’ You know what I do that you don’t? Travel around the world and experience other cultures on a daily basis.”

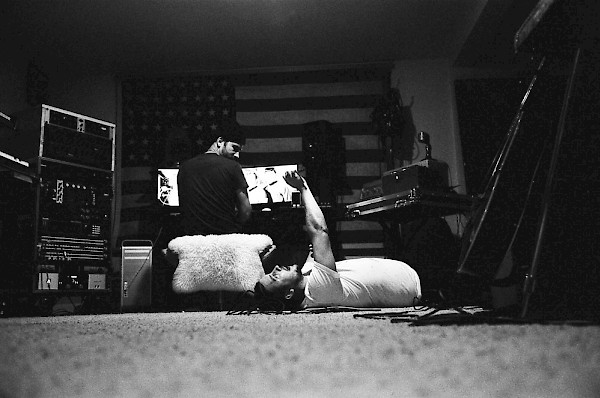

Gourley and Carothers in the studioNo matter the travels, Gourley and the band are super loyal to the Rose City.

Gourley and Carothers in the studioNo matter the travels, Gourley and the band are super loyal to the Rose City.

The group recorded much of Woodstock at band members’ studios in NE and SE Portland, Gourley says. (Gourley and bassist/vocalist Zach Carothers grew up in Alaska, while drummer Jason Sechrist was raised in Portland. The band is rounded out by keyboardist/vocalist Kyle O’Quin and guitarist/vocalist Eric Howk.) When not recording or touring, favorite PTM spots include B-Side Tavern, A & L Sports Pub, Le Pigeon and the Doug Fir Lounge.

“Portland is just a great city. It’s our favorite city in the country and I’m really glad we chose that as our base when we moved out of Alaska,” Gourley says.

The Lords of Portland moniker is a reference to the group’s perch atop the local music scene, homage to the band’s crew, and a vehicle for playing under-the-radar shows.

Gourley says the first Lords of Portland show was in Atlanta, and the idea is to “charge a small amount at the door and split it with everybody involved. It’s about supporting a group of friends and supporting your community and representing your community,” he says.

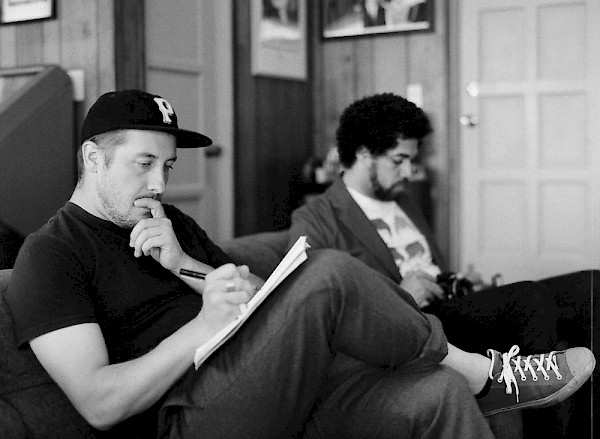

Zach Carothers writing alongside Danger MouseThe Last Artful, Dodgr’s cameo in the “Feel It Still” video, Gourley says, highlights the depth and breadth of the city’s music scene—a sonic diversity also featured on Woodstock. “You always have to progress,” Gourley says when asked about the multitudinous sonic influences and multiple producers on the new album (including superproducer Danger Mouse, Beastie Boy Mike D, and longtime partner Casey Bates).

Zach Carothers writing alongside Danger MouseThe Last Artful, Dodgr’s cameo in the “Feel It Still” video, Gourley says, highlights the depth and breadth of the city’s music scene—a sonic diversity also featured on Woodstock. “You always have to progress,” Gourley says when asked about the multitudinous sonic influences and multiple producers on the new album (including superproducer Danger Mouse, Beastie Boy Mike D, and longtime partner Casey Bates).

“It is so important,” Gourley says. “Living in Portland, I’ve seen it with bands: You get trapped in this bubble. You play the same bars every night, you play with the same bands every night. Part of having The Last Artful, Dodgr in the music video was showing how broad the music scene in Portland is. Dodgr’s music is one of the most exciting things happening in music right now.”

Through the eyes of Portugal. The Man: Jason Sechrist, Zach Carothers, John Gourley and Kyle O’Quin (from left to right on far left)Gourley says the group always finishes its recordings in the Pacific Northwest, surrounded by good people—and Woodstock was no different. “There’s just something about it,” he says.

Through the eyes of Portugal. The Man: Jason Sechrist, Zach Carothers, John Gourley and Kyle O’Quin (from left to right on far left)Gourley says the group always finishes its recordings in the Pacific Northwest, surrounded by good people—and Woodstock was no different. “There’s just something about it,” he says.

“The Portland vibe for me is, it’s all family. Portlandia makes it into a joke, which, if I’m being perfectly honest, it is a little exaggerated here and there. [But] we’ve taken [Portland] around the country with us.”

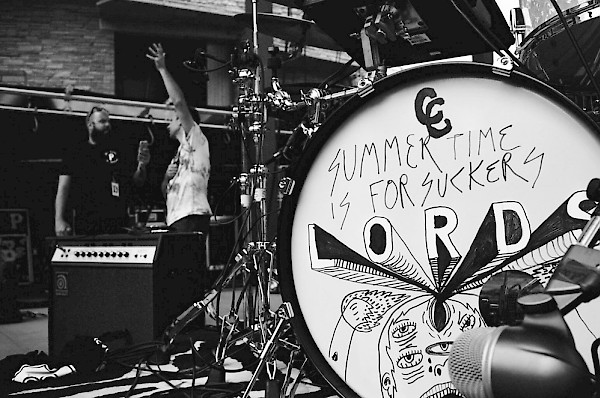

One of the things that has set Portugal. The Man apart from the alternative rock dustbin is its distinctive, sometimes disturbing artwork. Gourley has made virtually all of the art for the band—and that includes album covers, merch and more.

Gourley's psychedelic Sharpie sketches on the kick drum“There are darker things in the lyrics, and I like to represent that visually,” Gourley explains. Words, sounds and visuals can all help shape the group’s output in distinctive ways, Gourley suggests—in ways industry pros don’t always get.

Gourley's psychedelic Sharpie sketches on the kick drum“There are darker things in the lyrics, and I like to represent that visually,” Gourley explains. Words, sounds and visuals can all help shape the group’s output in distinctive ways, Gourley suggests—in ways industry pros don’t always get.

“When you talk to any label executive, for the most part, they’re going to hear a lyric and if you’re like, ‘Hey, I’m working at a diner,’ the exec is going to want you to have a music video where you’re working at a diner. I feel like the whole point of art and the visual aspect of this band is to present a contrasting image to help you see the song in a different light,” he says. “Or to understand that it’s not all bubble gum.”

Gourley's Forest for the Trees collaboration with INSA and Zach Johnsen that lives along the tracks of the MAX's Orange LineGourley downplays his artwork, but a glance at what he’s done with Portland-based graphic designer Austin Sellers in The Fantastic The suggests he’s no slouch. In Portland, anyone traveling along the Orange Line MAX tracks between SE Division and Powell will see a series of murals Gourley did with artists INSA and Zach Johnsen featuring lyrics from PTM's song "Colors."

Gourley's Forest for the Trees collaboration with INSA and Zach Johnsen that lives along the tracks of the MAX's Orange LineGourley downplays his artwork, but a glance at what he’s done with Portland-based graphic designer Austin Sellers in The Fantastic The suggests he’s no slouch. In Portland, anyone traveling along the Orange Line MAX tracks between SE Division and Powell will see a series of murals Gourley did with artists INSA and Zach Johnsen featuring lyrics from PTM's song "Colors."

In an act suggestive of the famous words scrawled on Woody Guthrie’s guitar, “This Machine Kills Fascists,” Gourley wrote “GO BACK 2 SCHOOL,” among other stuff, on one of his favorite guitars. It might not win him gear sponsorships, but it’s all part of his take-the-chance vision.

“Nothing is too precious for me,” he says. “I’ll draw on my ’63 Jazzmaster. It’s meant to be used; it’s not meant to sit on a wall.”

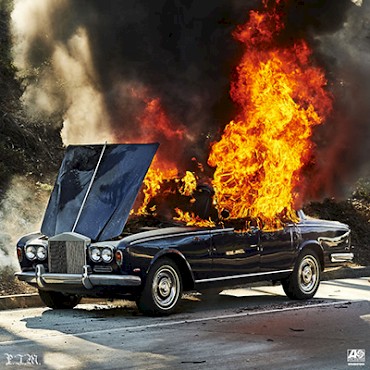

The Lords of PortlandThe new album will be out in early summer, Gourley says, before the group play homecoming shows at the Doug Fir Lounge and Edgefield in July. Whatever the ultimate chart position or units sold—a label’s priority but only part of an artist’s—Woodstock will mark not only a cathartic moment in the evolution of Portugal. The Man, but a big step forward for Portland’s music scene.

The Lords of PortlandThe new album will be out in early summer, Gourley says, before the group play homecoming shows at the Doug Fir Lounge and Edgefield in July. Whatever the ultimate chart position or units sold—a label’s priority but only part of an artist’s—Woodstock will mark not only a cathartic moment in the evolution of Portugal. The Man, but a big step forward for Portland’s music scene.

But what of Gloomin + Doomin—will we ever get to hear “those 40 songs”? Did Atlantic keep the masters? (You better believe it.) Was there a mysterious studio fire somewhere that we don’t yet know about?

‘Woodstock’ is out June 16 via Atlantic Records—listen to a new album cut below“Yeah, that’s the way we’ll talk about it,” Gourley chuckles. “I think eventually pieces of them will come out. We couldn’t focus on it. Gloomin exists as an idea. The material exists. There are a lot of different versions of things, a lot of different songs.

‘Woodstock’ is out June 16 via Atlantic Records—listen to a new album cut below“Yeah, that’s the way we’ll talk about it,” Gourley chuckles. “I think eventually pieces of them will come out. We couldn’t focus on it. Gloomin exists as an idea. The material exists. There are a lot of different versions of things, a lot of different songs.

“But at the end of the day, it took sitting down with my dad in Wasilla, Alaska, and him saying, ‘Hey, what’s taking so long with the record? Don’t you just go into the studio and record songs?’ Any other musician would be like, ‘My dad said some stupid shit to me about how recording music is easy.’

“But it is.”