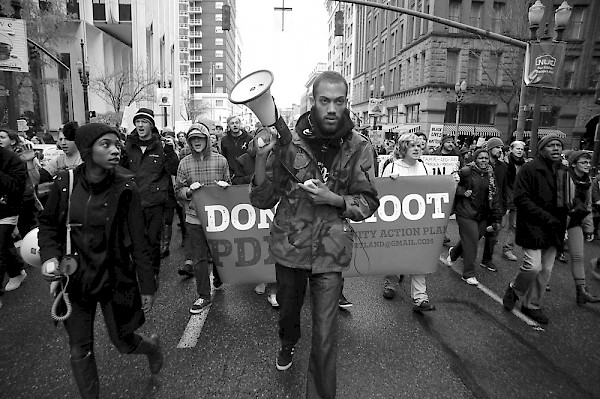

Waco the activist marching with Don’t Shoot PDX: Photo by Stephen Yates2012 was the year that three creatives craving independence, ownership and positions of influence to inspire and uplift their communities formed The Resistance in a two-bedroom apartment in Portland, Ore. At the time, I didn’t know Rasheed Jamal, but Mic Capes had told me about an artist he had run into at a barbershop and once the three of us got into the same room, it was clear we were all kindred spirits. The first conversations consisted of nonconformity, playing packed shows, being leaders affecting real change in the city, and inspiring kids. It was about creating a collective, a movement, a wave that not only consisted of rappers, but creatives revolutionizing what the scene was in that moment—but first, we had to get our names on a marquee.

Waco the activist marching with Don’t Shoot PDX: Photo by Stephen Yates2012 was the year that three creatives craving independence, ownership and positions of influence to inspire and uplift their communities formed The Resistance in a two-bedroom apartment in Portland, Ore. At the time, I didn’t know Rasheed Jamal, but Mic Capes had told me about an artist he had run into at a barbershop and once the three of us got into the same room, it was clear we were all kindred spirits. The first conversations consisted of nonconformity, playing packed shows, being leaders affecting real change in the city, and inspiring kids. It was about creating a collective, a movement, a wave that not only consisted of rappers, but creatives revolutionizing what the scene was in that moment—but first, we had to get our names on a marquee.

Glenn Waco is a writer, hip-hop artist and activist from North PortlandLooking back, it’s ironic: The Portland hip-hop scene once had some of the key infrastructure that it craves today, but many would agree that in the past it lacked the vibrancy electrifying the current scene.

Glenn Waco is a writer, hip-hop artist and activist from North PortlandLooking back, it’s ironic: The Portland hip-hop scene once had some of the key infrastructure that it craves today, but many would agree that in the past it lacked the vibrancy electrifying the current scene.

Remember all-ages venues? Remember Branx? The Blue Monk? Backspace? They’re gone. For profit, they were plucked by the same discriminatory vestiges of gentrification that have removed black and Latino natives from historically black and brown neighborhoods to accommodate implants who have no cultural connection to these spaces. The condos look beautiful, but right next to them are decaying buildings with memories rotting away with them as they crumble. Developers over the past two decades have sacrificed the soul of Portland at the altar of Portlandia. There are million-dollar houses in NE Portland, a place where current occupants wouldn’t have ridden their 10 speeds through 10 years ago.

Yet, a major point is being missed: Cities are built on 20- and 30-year development plans, so it’s not that there’s a lack of room for more affordable housing—some of us were just never a part of the development plan.

Despite this, we have cultivated something unique, beyond calculation. The city couldn’t predict what would blossom inside the womb of a district it planned on pushing black and brown people away from. Who could predict that the birth pangs of the coming economic boom would actually be in part due to black culture? Who could predict that the very same people who weren’t allowed to live and buy property on this land in the past could now actually generate revenue from their LLCs and entrepreneurship due to that very same migration of implants? At first glance, much may appear grim but these are growing pains so let’s not convolute this message: The city needs us more than we need the city.

Mic Capes, one-third of The Resistance hip-hop collective with Rasheed Jamal and Glenn Waco: Photo by Miss Lopez MediaI have never been wooed by any attempt city officials have made to extend olive branches because I recognize that we never needed co-signers in the first place. We used to dream of our names being on marquees; now we decide who’s on those marquees. We’re in magazines, receive national press, more of us are on tours. We have Totem, Bausik, Sam Lingle, Miss Lopez Media, Out of Line Productions, Grip Media and many more entities that produce consistent, quality content. We have We Out Here Magazine providing a platform for local artists to be heard with The Thesis; Cool Nutz and DJ Klyph on the radio waves. We have our own media. We’re literally building an industry on a grassroots level on land we were never desired to be on—so why would we fret over acceptance now when we’ve done all of this without being accepted?

Mic Capes, one-third of The Resistance hip-hop collective with Rasheed Jamal and Glenn Waco: Photo by Miss Lopez MediaI have never been wooed by any attempt city officials have made to extend olive branches because I recognize that we never needed co-signers in the first place. We used to dream of our names being on marquees; now we decide who’s on those marquees. We’re in magazines, receive national press, more of us are on tours. We have Totem, Bausik, Sam Lingle, Miss Lopez Media, Out of Line Productions, Grip Media and many more entities that produce consistent, quality content. We have We Out Here Magazine providing a platform for local artists to be heard with The Thesis; Cool Nutz and DJ Klyph on the radio waves. We have our own media. We’re literally building an industry on a grassroots level on land we were never desired to be on—so why would we fret over acceptance now when we’ve done all of this without being accepted?

Let’s build with local activists advocating social justice in the community so we can invest back into the community ourselves.

Mia O’Connor-Smith may not be Harriet Tubman but her Deep Underground (DUG) house shows have been the underground railroad for creatives of all genres. Salute to the Y.G.B. (Young, Gifted and Brown) collective as well. The first Portland Black Music Festival happened in spite of getting All Lives Mattered and this would have happened sooner or later anyway because the talent and power is undeniable (congratulations Farnell Newton). Venues that never had hip-hop acts are now opening their doors to the genre after being exposed to the culture (score one for The Resistance). I didn’t like the pay-to-play model so I connected with a venue and started my own concert series with We Take Holocene, empowering local artists to create their own opportunities to get paid. It doesn’t take much to have a DJ with a sound system host and charge at the door of your own house show.

What’s unfortunate is that the new neighbors have been urged to call the police ASAP if they see or hear anything disturbing in the neighborhood. And since it’s “illegal” for police to racially profile, can you see how they beat the case? That’s Ebonics for finding loopholes. Even with all these attempts of suppression, it’s fair to say our loophole is going to be the one we create. This is a culturally grassroots industry that we own pieces of, for now, and that’s why I urge creatives to acquire their business licenses and take advantage of this pried open window of opportunity.

Model Naisa Willingham and Waco during the filming of the video for his politically charged cut “Assata” (listen below), an ode to the Black Panther and godmother of Tupac: Photo by Miss Lopez MediaThe more people migrate to Portland, the more revenue will flow into Portland, so while we may be experiencing growing pains at the moment, now’s the time to create our own development plan to preserve the culture we’ve created within the city—it rests with us as a community. We can filibuster the city-sanctioned Hip-Hop Day or we can take Hip-Hop Day as our own and hone our focus. Let’s address what the scene is missing. Let’s meet in real life and design a blueprint moving forward. Let’s assign tasks and responsibilities. Let’s act unified with purpose. Let’s build with local activists advocating social justice in the community so we can invest back into the community ourselves. Everyone can be a gatekeeper of our own culture, so instead of sharecropping, let’s start harvesting our own crops.

Model Naisa Willingham and Waco during the filming of the video for his politically charged cut “Assata” (listen below), an ode to the Black Panther and godmother of Tupac: Photo by Miss Lopez MediaThe more people migrate to Portland, the more revenue will flow into Portland, so while we may be experiencing growing pains at the moment, now’s the time to create our own development plan to preserve the culture we’ve created within the city—it rests with us as a community. We can filibuster the city-sanctioned Hip-Hop Day or we can take Hip-Hop Day as our own and hone our focus. Let’s address what the scene is missing. Let’s meet in real life and design a blueprint moving forward. Let’s assign tasks and responsibilities. Let’s act unified with purpose. Let’s build with local activists advocating social justice in the community so we can invest back into the community ourselves. Everyone can be a gatekeeper of our own culture, so instead of sharecropping, let’s start harvesting our own crops.