Forgetting isn’t always a bad thing. The planet’s coming apart at the seams, and hey, weed is legal now.

But even in a nation as ahistoric as America—led by a president who never got the memo about poverty, slavery, or anything—memory is sanity. Lose one, you lose the other.

But even in a nation as ahistoric as America—led by a president who never got the memo about poverty, slavery, or anything—memory is sanity. Lose one, you lose the other.

This loss is at the heart of rock ensemble Typhoon’s Offerings, out January 12 on Roll Call Records. It’s the group’s fourth full-length, their first since 2013’s White Lighter, and one of the most ambitious, delicate, heartbreaking recordings ever by a Portland artist. Coupled with almost 40 dates across North America (their first stateside tour in three years) and a first-ever European jaunt, it could take the band to new heights.

“To me it really is a record of this period we’re living in, this moment in time,” says Kyle Morton, the group’s lead singer and songwriter.

That doesn’t bode well for 2018.

“The spiral is unspooling, the center couldn’t hold,” Morton intones on “Ariadne,” in one of numerous creepy-yet-infectious moments on this dystopian magnum opus. “We choked on our inheritance, and hell on earth is cold. Pray, I forgive you, brothers, sisters, thread my neck into the noose. It’s my only offering, and I pray that you refuse.”

Just how far Offerings will take Typhoon depends on the public’s ability to embrace dark themes, complex arrangements, and words like “chiaroscuro” and “consanguine.”

It’s heady, but authentic: Morton is a humble, well-read, curious Portland artist. When not running operations at Mississippi Studios or diving into circuitry pre-tour at Old Town Music, he spends time at Another Read Through, Cinemagic and Beacon Sound. In conversation, he casually drops phrases like “sine qua non” and references as diverse as Samuel Beckett, Westworld, Dan Deacon, Mark Zuckerberg, Dostoyevsky, Žižek, even “Peter Pan and his happy thought.”

The band’s artist page on Roll Call Records describes the new album as the sound of “a Fellini film, a Bosch painting, and a Rorschach drawing.”

Yet there’s nothing overly intellectual about Offerings. It hits home, viscerally, by reflecting two truths: the internal, like a loved one’s dementia, or Alzheimer’s, or those little pills you take every morning and night; and the external, like America’s collective current cognitive dissonance, or Portland’s deepening homelessness crisis.

Why such a dystopian record, Kyle?

A sigh. Morton doesn’t mince words, and everything he says or sings is leavened with humor. “I would say because we’re getting there. Look, I root for civilization, but it’s the underdog in this situation.”

Kyle Morton of Typhoon at the Crystal Ballroom in 2013—click to see more photos by Autumn AndelMorton’s voice is a gossamer thread that connects all of Typhoon’s work. It’s built with strength and vulnerability and holds the listener in a quavering grip that intensifies.

Kyle Morton of Typhoon at the Crystal Ballroom in 2013—click to see more photos by Autumn AndelMorton’s voice is a gossamer thread that connects all of Typhoon’s work. It’s built with strength and vulnerability and holds the listener in a quavering grip that intensifies.

On the shimmering “Coverings,” Morton shares the songwriting for the first time with a Typhoon band member, violinist and vocalist Shannon Steele. It’s a good thing.

“You gotta learn how to live on an ever-shorter tether,” Steele sings on “Bergeron,” in the steal-the-show mode à la Régine Chassagne of Arcade Fire. Steele’s lead vocal on “Coverings,” levitating above lush guitar lines reminiscent of Band of Horses, is one of the album’s best moments, a song you want on loop.

“She just sort of has this crystal-clear high voice that no matter what else is going on, it kind of sits above everything and is ethereal and heavenly,” Morton describes.

But Morton’s narrator, a man who is losing his memory and mind, is the unifying vision on Offerings. He says it’s informed partly by his own suffering, which started with a tick bite and Lyme disease during his childhood. Yet he manages a light touch, even describing his own suffering:

“Inasmuch as my own finitude and mortality and struggles with health things from one day to the next, whether it’s a major hospitalization or having to feel fatigued and shitty for weeks on end, it really is kind of...,” he pauses, “how to put it? Did you watch Westworld at all, the HBO show?”

Other explications of his approach to making art by working from the wound similarly end with humble disclaimers, via cultural references: “I don’t think I write or make music out of any overflowing talent; it’s kind of more the opposite, out of my own pain and scarcity and poverty. I’m kind of ripping off Beckett.”

Morton says his health is “stable” right now, “fingers crossed.” “It seems to have kind of reached a workable plateau,” he notes.

Yet the recording of Offerings proved an occasionally taxing deep dive, Morton recalls.

Yet the recording of Offerings proved an occasionally taxing deep dive, Morton recalls.

“As the writer, you have to have a broader view than the character that you’re writing, but there were times when I spent so much time thinking about memory loss that I really did start to feel like I was exhibiting the symptoms.

“And we were all working—music doesn’t pay the bills just yet. Things started feeling very cyclical, and like time was looping.”

Will music ever start paying the bills for Typhoon?

The group’s 2010 full-length Hunger and Thirst and 2011 EP A New Kind of House, on Portland label Tender Loving Empire, have each sold more than 14,000 copies, the label confirms. 2013’s Roll Call Records debut White Lighter peaked at #105 on the Billboard 200, selling 25,000 copies in the US alone.

“Pre-orders for [Offerings] have surpassed all prior records and tickets across the country are moving quickly as well,” says band manager Mark Jourdian; that includes selling out of 1,000 blood red LPs as well 1,000 autographed CDs.

It’s a long recording at 70 minutes, whose wonders and delights can be spiny and spicy. Morton won’t make predictions about the album—and friends are hedging their bets.

“I have a bunch of friends who said, ‘This is my favorite thing you’ve done, [but] I don’t think it’ll be a commercial success,’” Morton says. Or, “‘Best thing you’ve ever done, it’s not going to work.’”

Then again, NPR Music's Bob Boilen reportedly cried upon first listen. Besides, commercial success has never been top priority for Typhoon; Morton describes it as “a byproduct that we’re looking for.”

Offerings is a continuation of the band’s emotionally complex vibe, akin to older songs like “Dreams of Cannibalism” or “Young Fathers” (albeit with less horns). It’s sombre but fun.

The haunting video for “Rorschach” is maybe the best indication of the album’s potential. Directed and edited by Matthew Thomas Ross, it’s a mesmerizing work that starts with a sequence of Morton in what seems like a 1950s institutional setting, sitting across from a clinician who shows him disturbing Rorschach images. It ends with a fiery climax that seems a metaphor for a descent into insanity.

“Oh, oh, how you gonna hold on, how you gonna hold on / You know that you can’t,” the group sings in the rollicking, intense, symphonic rock ditty—a line not on the official lyric sheet.

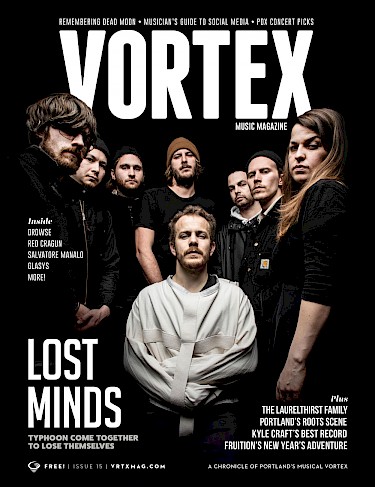

Clockwise from top left: Devin Gallagher, Kyle Morton, Toby Tanabe, Tyler Ferrin, Pieter Hilton, Shannon Steele, Alex Fitch, Dave HallThroughout their ambitious, unique journey, Typhoon has always centralized band-as-family, bringing anywhere from eight to 11 musicians—not including their supporting cast and friends. Along the way, they’ve forged connections in Oregon music scenes from Salem to the Orange House to Pendarvis Farm and Pickathon.

Clockwise from top left: Devin Gallagher, Kyle Morton, Toby Tanabe, Tyler Ferrin, Pieter Hilton, Shannon Steele, Alex Fitch, Dave HallThroughout their ambitious, unique journey, Typhoon has always centralized band-as-family, bringing anywhere from eight to 11 musicians—not including their supporting cast and friends. Along the way, they’ve forged connections in Oregon music scenes from Salem to the Orange House to Pendarvis Farm and Pickathon.

It’s also one of a couple of themes music journalists have at times leaned too much on when covering Typhoon, Morton says. “I think the size of our band has been overrepresented,” he says, laughing. “I [also] think the water puns are lazy.”

Perhaps, in focusing on the logistical problems of taking up to 11 musicians on the road, the media have misunderstood how logical and essential it is—in a world gone mad—to create a separate, sane world of music through people. The approach is even suggested by the name of their Instagram page: Typhoon Family Vacation. Besides Morton (guitar, vocals) and Steele (violin, vocals), Tyler Ferrin (guitar, keys), Toby Tanabe (bass), Alex Fitch (drums), Dave Hall (guitar), Devin Gallagher (mandolin) and Pieter Hilton (drums) recorded Offerings.

“We’re down to eight,” Morton says. “Just eight. And it might be seven on the next tour. We’re all sort of getting older and we all have jobs. I’m being a little more flexible these days with who can make it on this tour.”

“I love all these people,” he adds. “They’re sort of my other family.”

Even Morton’s legal family is coming on tour. His wife is Danielle Sullivan from Wild Ones, one of numerous Portland artists joining Typhoon on tour. (Others include Mimicking Birds, Matt Dorrien, Sunbathe and Amenta Abioto.) The band plays its penultimate date on Friday, February 23 at the Crystal Ballroom with his better half's band opening.

The couple just bought a house in the Roseway neighborhood. So Morton’s been having “fun” fixing broken shower knobs turned projectiles (thanks to water pressure), refinishing floors, etc. Of course, we have to ask: You two pregnant yet?

“Not as yet, despite all my best efforts,” comes Morton’s laughing response.

Morton took over engineering during the recording of Offerings. In DIY fashion, the band laid down tracks in a big basement room at the Oregon Portland Cement Building next to the Hawthorne Bridge.

As Morton tells it, the process of creating a dystopian album about a narrator who is “losing all his memories, losing everything that constitutes him as a person,” at times turned into “total masochism.”

“I’ve had suffering in life, but this was totally self-inflicted,” Morton says. “It’s a big record, with a wider scope than anything I’ve done before.”

Musicians engineer their own sessions a lot these days, but they still don’t think like studio engineers. At one point, on “Empiricist,” Morton went down a REAPER wormhole using the audio software. He realized he had laid down 300 tracks on that song alone, a no-no given the demands that can put on a computer’s hard drive. Of course, something went wrong.

“There was a certain point where all the folders in my effects basically got misallocated,” Morton recalls. “I was up all night trying to work backwards from this thing. At this point I realized that this recording was probably going to drive me into the insane asylum.”

Hinting at the stages of grief, the album is organized in four movements (Floodplains, Flood, Reckoning and Afterparty) that represent the phases the main character goes through: realization, struggle, acceptance, death. On “Wake,” “Unusual” and “Ariadne,” Morton says, there are choral parts somewhat inspired by Steve Bannon, for which he sought “a cultish feel, or old gospel-ish feel but with a creepy undertone.” Other techniques Morton used include creating dissonance using vocals from all the notes in the chromatic scale as well as layering the same track 100 times, he says.

CLICK HERE to join the Vortex Access Party and get a copy of the mag delivered to your door each quarter—plus access to exclusive giveaways and prizes. Cover photo by Sam Gehrke.So when catharsis happens at the sound of a door opening 8 minutes into its finale, the 13-minute track “Sleep,” it’s strange and satisfying: a chorus of perhaps the whole band in typically perfect harmony, reduced to sound like a drunken Pogues singalong in an Irish bar, crossfaded into a funky, jangly groove reminiscent of Modest Mouse or The Shins.

CLICK HERE to join the Vortex Access Party and get a copy of the mag delivered to your door each quarter—plus access to exclusive giveaways and prizes. Cover photo by Sam Gehrke.So when catharsis happens at the sound of a door opening 8 minutes into its finale, the 13-minute track “Sleep,” it’s strange and satisfying: a chorus of perhaps the whole band in typically perfect harmony, reduced to sound like a drunken Pogues singalong in an Irish bar, crossfaded into a funky, jangly groove reminiscent of Modest Mouse or The Shins.

The lyrics are a tangled code not included in the official lyrics; perhaps sometimes musical heartbreak should be mysterious. Their form hides in an aural mist that parts to reveal silhouettes like, “Our strength was in the moment when we were weak.”

It’s the kind of complex, unique sound that might fairly be described as a “Portland sound,” if such an ephemeral thing exists. “Oh yeah, there’s something,” Morton says when asked—then also struggles to describe it. “I don’t know if it’s seasonal affective disorder, or kind of the grunge tradition in the city, but it’s just there.”