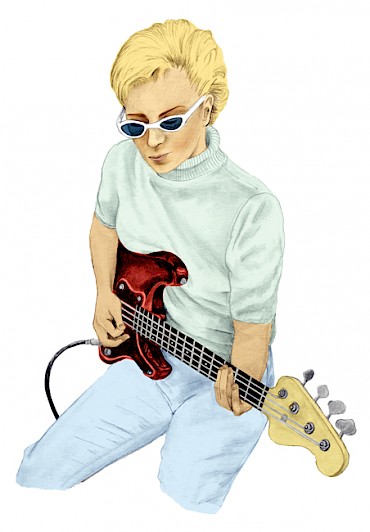

“Not a household name, but she’s been in your head all day,” Portland’s Laura Veirs sings on her tribute "Carol Kaye," which honors the influential bassist from Everett, Wash.: Illustration by Rachel Frankel“A note doesn’t have sex to it—you either play it good or you don’t play it good,” bassist Carol Kaye succinctly states. “Some people can’t handle that, especially some men... when you hear somebody with balls, that’s me,” she laughs.

“Not a household name, but she’s been in your head all day,” Portland’s Laura Veirs sings on her tribute "Carol Kaye," which honors the influential bassist from Everett, Wash.: Illustration by Rachel Frankel“A note doesn’t have sex to it—you either play it good or you don’t play it good,” bassist Carol Kaye succinctly states. “Some people can’t handle that, especially some men... when you hear somebody with balls, that’s me,” she laughs.

“She can really play it, she can really lay it down,” Portland’s Laura Veirs sings on “Carol Kaye,” a tribute to the prolific bass guitarist from Everett, Wash., from her 2010 record July Flame. Rattling off song titles like “Good Vibrations” and “Help Me Rhonda” by The Beach Boys, Simon & Garfunkel’s “Homeward Bound,” “Feelin’ Alright” by Joe Cocker, The Monkees’ “I’m A Believer,” the “Theme from Mission: Impossible,” and the Quincy Jones-penned, Ray Charles-performed “In the Heat of the Night,” Veirs’ sweet little folk ditty barely scratches the surface of Kaye’s legendary, 10,000-plus session career. The only female member of L.A.’s famous studio players the Wrecking Crew, Kaye really did lay it down with Sam Cooke, Frank Zappa, Richie Valens, Sonny & Cher, The Righteous Brothers, Count Basie, Barry White and so many more.

“Not a household name, but she’s been in your head all day,” Veirs sings, aptly paying homage while encapsulating a sad but true reality: The achievements of women and female-identifying individuals have been consistently overlooked throughout the history of music.

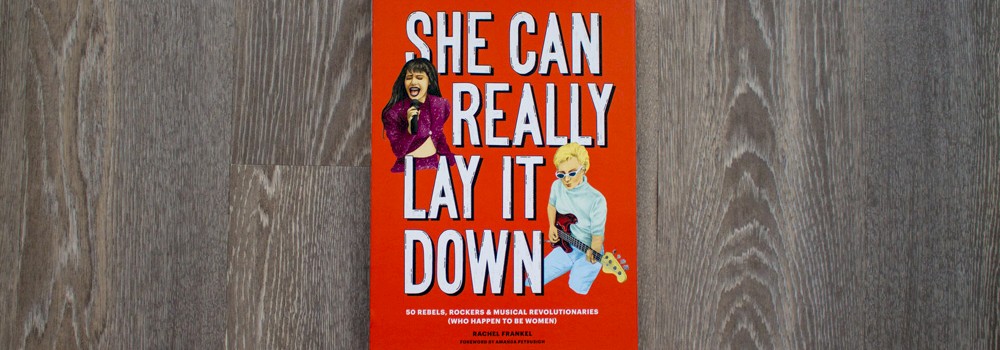

Starting with Elizabeth Cotten and Memphis Minnie (both born in the 1890s) and working her way up to the present day with Neko Case, Lauryn Hill, M.I.A. and Amy Winehouse, musician, author and illustrator Rachel Frankel aims to set the record straight with She Can Really Lay It Down: 50 Rebels, Rockers & Musical Revolutionaries (Who Happen To Be Women)—a chronological catalogue of artists who “do not presently, and did not previously, receive proper recognition and exposure for their historical, social and musical contributions to society and culture,” Frankel tells.

Researched, written and illustrated by Frankel, 'She Can Really Lay It Down' is out now via Chronicle Books“Cis male musicians often enjoy the luxury of having their music absorbed and reviewed without any consideration of their gender presentation, while women and non-binary musicians often have to answer questions about how that impacts the music they make,” she continues. These artists shouldn’t be placed “on some sort of alien pedestal, as if we have suddenly started to make music that people are interested in hearing. Actually, we’ve always been here.”

Researched, written and illustrated by Frankel, 'She Can Really Lay It Down' is out now via Chronicle Books“Cis male musicians often enjoy the luxury of having their music absorbed and reviewed without any consideration of their gender presentation, while women and non-binary musicians often have to answer questions about how that impacts the music they make,” she continues. These artists shouldn’t be placed “on some sort of alien pedestal, as if we have suddenly started to make music that people are interested in hearing. Actually, we’ve always been here.”

In 2014, Frankel was living in the Bay Area and playing music with her dream pop band Phosphene. “With each show we did, I started picking up on the subtle and not-so-subtle ways women are treated differently as musicians,” she tells. “It didn’t take long for me to connect the dots of my own experiences to the discrimination and erasure that women have experienced, not just within music history, but the broader scope of history at large. Once you notice the void is there, you see it everywhere.”

No matter how unsung many of the featured musicians were during their careers and lives, you cannot deny the powerful sonic presence they’ve left behind. She Can Really Lay It Down demonstrates how the legacies of pioneering artists have carried over to contemporary artists.

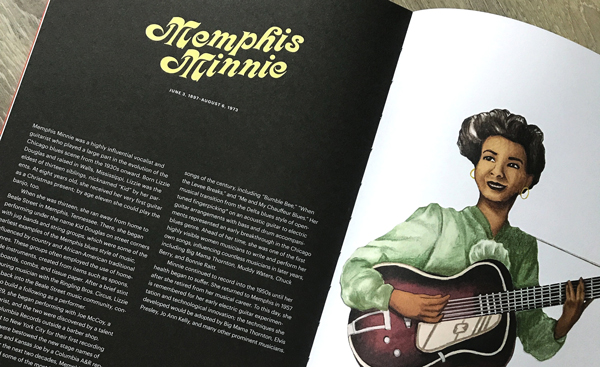

“You can easily connect Alynda Segarra [of Hurray for the Riff Raff] back to Memphis Minnie, or Beyoncé to Selena,” Frankel says, which inspires you to imagine how these meaningful histories can shape future generations if these biographies are simply shared more widely.

From left to right: Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Beyoncé and M.I.A.: Illustrations by Rachel FrankelAnd it goes beyond just groundbreaking musical talent. Underrepresented forebears like Sister Rosetta Tharpe (a posthumous Rock & Roll Hall of Fame inductee) and her gospel blues (which influenced Little Richard, Chuck Berry, Elvis Presley, Aretha Franklin and Johnny Cash) and ranchera singer and Mexican icon Chavela Vargas “are some of the most captivating stories in the book,” Frankel says. “These are two women who were living openly queer lives in the 1940s and ’50s. Considering the stigmas that still exist nearly 70 years later, it’s truly incredible to think about.”

From left to right: Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Beyoncé and M.I.A.: Illustrations by Rachel FrankelAnd it goes beyond just groundbreaking musical talent. Underrepresented forebears like Sister Rosetta Tharpe (a posthumous Rock & Roll Hall of Fame inductee) and her gospel blues (which influenced Little Richard, Chuck Berry, Elvis Presley, Aretha Franklin and Johnny Cash) and ranchera singer and Mexican icon Chavela Vargas “are some of the most captivating stories in the book,” Frankel says. “These are two women who were living openly queer lives in the 1940s and ’50s. Considering the stigmas that still exist nearly 70 years later, it’s truly incredible to think about.”

While a mere 50 selections is not nearly enough to highlight all who are deserving, Frankel’s choices were “influenced by the respective musician’s degree of activism and advocacy for social justice,” making these empowering vignettes “incredibly relevant and important” in today’s world.

“Painful” omissions, by her account, include “Laura Veirs for sure, along with Carrie Brownstein and Corin Tucker from Sleater-Kinney.” But the recently departed Janet Weiss—now in Slang and always of Quasi—gets her own ode because “many drummers don’t often get their due recognition, not to mention she is just about the best rock drummer around period. Esperanza Spalding and Beth Ditto are two other Portlanders who were definitely contenders as well.”

As for the next round, Frankel is keeping her eye on Kathy Foster’s energetic projects Hurry Up and Roseblood, plus captivating folk singer Haley Heynderickx and the multifaceted emcee Dodgr.

“Music is a fellowship,” the versatile Meshell Ndegeocello extolls. “If you want to count me out because I refuse to conform to ideas of gender or of genre, you’re only making a fool of yourself. Time will tell.”