Cloudy October performing in 2011In 2004, a friend of Cloudy October's lost her mother. After, this friend asked him to help move her mother’s things. She couldn’t pay Cloudy, she said, but he was free to take what he liked. In the corner was a stack of over a thousand records. Cloudy grabbed the whole pile.

Cloudy October performing in 2011In 2004, a friend of Cloudy October's lost her mother. After, this friend asked him to help move her mother’s things. She couldn’t pay Cloudy, she said, but he was free to take what he liked. In the corner was a stack of over a thousand records. Cloudy grabbed the whole pile.

The records were definitely different than what Cloudy was used to—most of them would qualify as “elevator music”—and they sat in his apartment for years. One would think eventually he would throw them out, but he couldn’t, he says. Not without listening first.

And so Cloudy spent an entire year listening to those records. It wasn’t just a few seconds of the beginning and moving on—he listened to every single song. “Each one has the potential to contain a hidden gem,” he says. “The idea of missing something precious makes me livid.”

What emerged from this were selected instrumental samples, around 100 in total, and only 10 of these made their way into the first cut of 2010's The Aviator is Dead.

Based on this, it's easy to understand why Cloudy October, one of Portland’s most popular rappers from 2012, has taken over five years to produce his newest album.

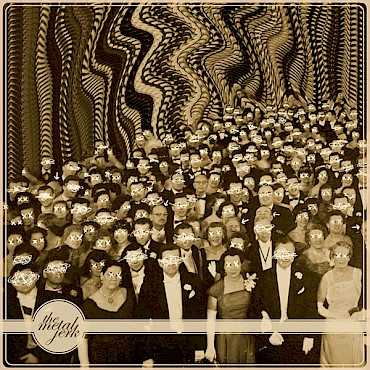

Cloudy October's last album, 'The Metal Jerk,' came out in 2012As soon as you enter Cloudy’s apartment, it's clear you're somewhere special.

Cloudy October's last album, 'The Metal Jerk,' came out in 2012As soon as you enter Cloudy’s apartment, it's clear you're somewhere special.

His pantry shelves, rather than being stocked with food, instead serve as shelf space for his video tapes. It’s not just a few shelves, either—his kitchen is lined from top to bottom and on multiple walls with hundreds of video tapes. He grabs one and shows it to me.

“Have you ever watched The Godfather on video?” he asks excitedly. “There’s this hissing sound; it’s an old-school quality you can’t get with the DVD. It’s beautiful.”

Every inch of his apartment has a story, either humorous or provocative. All of his books are about sex or philosophy, or a combination thereof. Three Aesop Rock album covers are above his TV. In the doorway leading to his kitchen, the words “erectile dysfunction” catch the eye—it’s a brochure he has, one of many, which are stacked in those plastic dividers you see in a doctor’s office. Cloudy displays some for his visitors. He tells me I am free to take one.

We move into the main room of his one-bedroom apartment. There are five DVDs sitting in front of his TV—this is what he’s watched this week—and they run the gamut in terms of content: Get on Up, the James Brown biopic; Power Rangers, not the new one but the version from 1995; The Last Dragon, the martial arts comedy cult classic from the 1980s; and then, not one, but two copies of Thor, one regular and the other a Blu-ray version.

He shows me all of his recording equipment, which fits snugly into his custom-built desk. A fake bat hangs from the ceiling, with parts of pillow stuffing strung around, giving the appearance of clouds. This room is a sanctuary of information.

I ask him if he ever gets bored here. It seems as if he’s never even considered that thought before. “No, never,” he says. A huge smile comes across his face. “I haven’t been bored since I was four years old.”

Cloudy starts to play a song on his computer. Three seconds in, he pauses the music. “Eddie Murphy, The Golden Child,” he says. He swivels back to his computer. Seconds later, he pauses it again. “You recognize the beat, right? It’s the theme from The Munsters, you remember that show?” We’re at the end of the first verse when you hear a teenage girl shout “ewww!” He hits a full stop here. “That sound, that girl yelling 'ew'? That’s D.J. from Full House. I spent an all-nighter watching that show, just to come away with that sound.”

That "ew" serves a very particular purpose for this song: In talking about a woman he’s eyeing, it follows the line, “My homies wonder why I don’t hit it but get this / her mother and my mother are siblings.” The idea, he says, originated from a conversation with his friend. The beat came first, and the word "cousin" kept popping up in his thoughts. He thought about how attractive his cousin is, and words started flowing. Out came one of his most popular songs, “Two Rude Dudes.” Wasn’t he embarrassed, or nervous, to put out a song like that? “Hey, I didn’t say I did it,” he says. “It’s real, though, so I’ll talk about it.”

One might say Cloudy takes his time making an album, but it’s not about procrastination—he spends every waking minute on his rap. His process, though, is just more thorough than most.

In theory, one could make a rap album in a week. Moreover, the ubiquity of recording equipment has made everyone a producer. In today’s world, it’s too easy to take a four-bar sample and loop it into a rap song. You can do it yourself in your own bedroom. You don’t need a practice space, you don’t even need bandmates.

This is why rappers, in order to stand out, must push themselves to be original. You have to sample the things that nobody’s ever heard before. To be truly innovative, you have to hear the things that others don’t.

Many artists act instantly on moments, a rush of inspiration; others are more calculated, thorough and persistent—they’re the ones who collect these moments over time in order to weave something bigger, a narrative. Cloudy is of the latter camp. “Scrolling” is what he’s named his process: It involves the collection of tens of thousands of ideas, taking place over the span of several years. Every nuance in a situation, every line or rhythm or thought that resonates with him, is recorded in a notebook or on a Word document. Once he’s ready, he culls this list, whittling it down to about 5 percent of what it was before, a small selection of ideas that aren’t just fresh, but “absolutely golden.” This is how, by the final product, you know that every word you hear, every beat and quote and irreverent sound effect that’s sampled, has survived Cloudy’s test of intense scrutiny.

This is how you make a song nobody’s ever heard before.

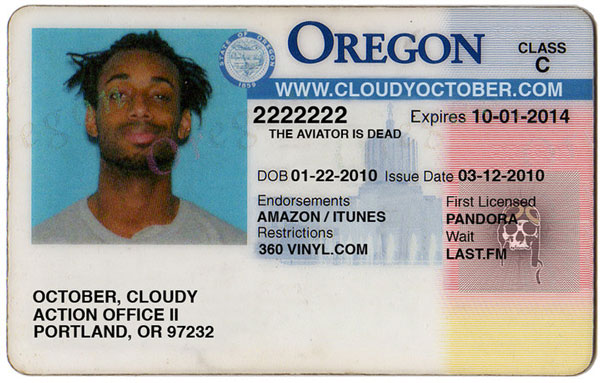

A poster from 2010 around the time Cloudy October's debut EP, 'The Aviator is Dead,' was releasedCloudy’s first two albums, The Aviator is Dead and The Metal Jerk, quickly earned him a reputation as one of the best rappers in Portland. Often, especially in the wake of releasing a hit or a popular album, artists feel this pressure to keep putting things out, to stay on the public’s radar. Cloudy feels it too—it’s a recurring anxiety where he questions if he’s at the level of success he knows he’s capable of reaching. Perhaps he could be doing more. Heavy as it is, it’s not enough for him to rush something or to compromise his product. Mediocrity is not in his constitution; if he isn’t proud of it, ecstatic, then the world doesn’t hear it.

A poster from 2010 around the time Cloudy October's debut EP, 'The Aviator is Dead,' was releasedCloudy’s first two albums, The Aviator is Dead and The Metal Jerk, quickly earned him a reputation as one of the best rappers in Portland. Often, especially in the wake of releasing a hit or a popular album, artists feel this pressure to keep putting things out, to stay on the public’s radar. Cloudy feels it too—it’s a recurring anxiety where he questions if he’s at the level of success he knows he’s capable of reaching. Perhaps he could be doing more. Heavy as it is, it’s not enough for him to rush something or to compromise his product. Mediocrity is not in his constitution; if he isn’t proud of it, ecstatic, then the world doesn’t hear it.

As fun as Cloudy’s story is, there’s one glaring thing we must acknowledge: What if, after five years of hard work, the thing that Cloudy’s been working on isn’t well received? What if people don’t like it, or they don’t even hear it?

This question hits him when I ask it, but then he gives me the same look as when I asked about boredom. “I know people are going to like it, there’s no way they won’t,” he says.

How can he be so sure? I ask.

“They’ll like it because it’s honest.”