Illustration by Maria RodriguezFingering accurate patterns of notes anchored to complex chord changes at 300 beats per minute is something only a few musicians can do. That’s up to three times the speed of the average runner’s heartbeat, or more than twice as fast as the tempo of Lady Gaga’s hit “Bad Romance.”

Illustration by Maria RodriguezFingering accurate patterns of notes anchored to complex chord changes at 300 beats per minute is something only a few musicians can do. That’s up to three times the speed of the average runner’s heartbeat, or more than twice as fast as the tempo of Lady Gaga’s hit “Bad Romance.”

Count Portland musicians Sebastian Silva and Denzel Mendoza among them.

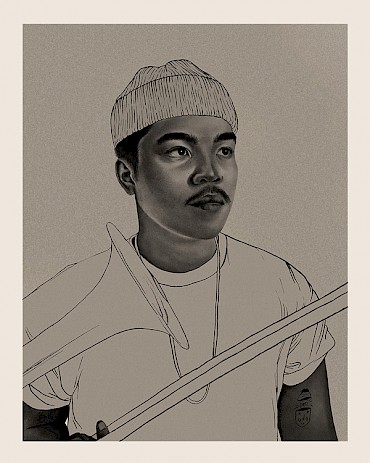

Silva rips death metal riffs at pulse-pounding speeds on his Jackson Dinky electric guitar. He recently completed two European tours with rising goth rockers Idle Hands.

Mendoza blasts jazz trombone at light speed on his Best American Craftsman Elliot Mason series instrument. He won a Grammy last year with John Daversa and plays in several local projects, including Haley Heynderickx and Kulululu.

Both men are 23-year-old undocumented immigrants who came to the U.S. as children, then qualified for the Obama-era Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, program. They have temporary legal status to live and work here. But that status is precarious and doesn’t allow them to leave the country.

In March, immigration authorities ruled Silva is not “extraordinary” enough to merit an artist visa, so he is now living with relatives in Guadalajara, Mexico, rather than home in Portland with his bandmates. Mendoza has skipped lucrative gigs in other countries and an immigration lawyer told him his chances of scoring a visa weren’t “promising.” Now he’s trying to save the thousands needed to apply.

Music is amazing at building bridges, especially here in Bridge City. But what happens when immigration politics constrain art, careers and economic growth? What bridges aren’t being built when xenophobic politics rule and building walls is prioritized? What’s lost when immigrant musicians can’t tour and international artists can’t come here from afar?

Portland musicians and others affected by the wall-building say federal immigration policies are a millstone. Yet they continue to do what they do, in amazing fashion.

Shredding Visas

When opportunity knocks in the music business, one better be ready. Guitarist Sebastian Silva was. “Idle Hands got offered these European tours like right off the bat,” Silva recalls. “I thought I would bite the bullet and just fly and do it, even though I knew my chances of returning to the U.S. were very slim.” He’d previously turned down offers to play in Europe and Japan, but this time, “I thought, ‘Why should I wait when [the opportunity] is going to be happening right in front of my face?’”

Guitarist Sebastian Silva of Idle Hands and Silver Talon: Photo by Peter BesteImmigration visas don’t move at the speed of metal. Silva’s application was filed January 18, and the response was dated March 7. A few days later, on the last day of Idle Hands’ first European tour, Silva was waiting patiently in Amsterdam, alone—his bandmates had flown out. A text arrived from Nathanial Myers, Silva’s sponsor and head of Portland-based doom and black metal label Eternal Warfare Records. Bad news.

Guitarist Sebastian Silva of Idle Hands and Silver Talon: Photo by Peter BesteImmigration visas don’t move at the speed of metal. Silva’s application was filed January 18, and the response was dated March 7. A few days later, on the last day of Idle Hands’ first European tour, Silva was waiting patiently in Amsterdam, alone—his bandmates had flown out. A text arrived from Nathanial Myers, Silva’s sponsor and head of Portland-based doom and black metal label Eternal Warfare Records. Bad news.

“Hey man, I’m sorry to tell you but they denied your application,” it read. Returning to Bridge City was no longer an option. Because of the visa denial, Silva wasn’t even allowed to fly through New York, so he spent a week plane hopping and living in airports. Ultimately, he ended up with relatives in Guadalajara he barely knew. “It was kind of crazy reconnecting with my family [there] for the first time in 14 years,” he says.

Silva’s I-129 petition for an O-1, or artist, visa under the Immigration and Nationality Act was denied with a river of jargon. “You provided articles, testimonials, reviews, media kit and concert reviews,” U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) wrote Myers and Silva, whose legal name is José Silva Figueroa, yet “no evidence was provided to establish that selling out [a] 1,500-seat venue constitutes a record of major commercial or critically acclaimed successes.”

Idle Hands just released a new album, Mana. Myers says it has “huge stuff coming up.” Silva’s ability to absolutely shred on electric guitar has been a big part of that, says Bryce VanHoosen, who plays with Silva in local heavy metal band Silver Talon.

“I think we all feel a bit powerless in our inability to bring our friend and bandmate home,” VanHoosen says. Portland has been Silva’s home for 13 years, since he moved here at age 10. “No one is trying to do anything illegal here—Sebastian has been amicable in going through the motions with immigration, filing the appropriate paperwork, and paying the massive amounts of money the U.S. government wants to do this stuff.”

When Silva went back to Europe in April for a second tour, he felt groundless.

“I just remember thinking, ‘Oh my God, am I going to be stuck in Mexico [after this tour]?’” Silva recalls. “Every day I would think of the worst-case scenario and kind of replay it in the back of my mind. I would keep quiet to myself a lot.”

Silva could have skipped the tours and stayed in the U.S., but music is his profession, what he’s good at. He’s delighted ears in Belgium, Sweden, the United Kingdom, Germany, the Netherlands, the Czech Republic and beyond.

“When I see everybody [in the audience] and they’re all different, and when we’re playing our music, it’s like nothing else matters,” Silva says. “And that’s the way it should be, we can all just get along and we can find the things we have in common. If we start looking at things that way we might be able to reach a better place eventually.”

Silver Talon's Wyatt Howell, Gabe Franco, Sebastian Silva and Bryce VanHoosen: Photo by Peter BesteBut Silva will not be able to tour stateside, Myers says, unless a new path presents itself. Sometimes, Myers suggests, such a path can be inscrutable. “I think he can pull it off, but he’s going to have to do it a different way,” Myers adds mysteriously, “and it’s a way I don’t want to talk about.”

Silver Talon's Wyatt Howell, Gabe Franco, Sebastian Silva and Bryce VanHoosen: Photo by Peter BesteBut Silva will not be able to tour stateside, Myers says, unless a new path presents itself. Sometimes, Myers suggests, such a path can be inscrutable. “I think he can pull it off, but he’s going to have to do it a different way,” Myers adds mysteriously, “and it’s a way I don’t want to talk about.”

For now, Silva’s a frizzy-haired Portland rocker who speaks perfect English and “fourth grade” Spanish, living 2,000 miles from his Oregon home and bandmates. On the way back to Guadalajara in June, a Mexican customs agent asked him, “Are you sure you’re Mexican?”

“I dream in English, I speak English, I feel everything in my second tongue. I’ve pretty much lived my whole teenage years and my musical career in America,” Silva explains. “I just wish I were born on the right side of the border, it would have just made my life so much easier.”

VanHoosen sees Silva’s courage as inspiring. “It makes having to leave your [day] job in order to tour seem small by comparison.”

Illegal Son

The day after President Trump won, Denzel Mendoza was despairing, but he rambled with his trombone to a house party where he met another Filipino musician, Haley Heynderickx. She invited him to open for the band, and the resultant 20-minute solo trombone set won him an invitation to join her and became the basis for his new trio, Illegal Son.

Denzel Mendoza at Revolution Hall with Haley Heynderickx in 2018—click to see more photos by Ignacio Quintana“That was the day I came out to strangers, and said, ‘Listen, my name is Denzel Mendoza and I’m undocumented, and unafraid to tell you my story. I don’t know what’s going to happen to my life or to others, so right now I’m going to play how I feel.’”

Denzel Mendoza at Revolution Hall with Haley Heynderickx in 2018—click to see more photos by Ignacio Quintana“That was the day I came out to strangers, and said, ‘Listen, my name is Denzel Mendoza and I’m undocumented, and unafraid to tell you my story. I don’t know what’s going to happen to my life or to others, so right now I’m going to play how I feel.’”

Mendoza’s improv is a metaphor for undocumented life. “Life, for me and for every other undocumented immigrant out there, is completely improvised. Honestly, one day everything could be okay, and then the next day it could be gone.”

Mendoza was in fourth grade, part of a Filipino family from Singapore, when his father “just straight up left.” His words are still laced with pain when he recalls a special concert in front of family “and the only empty seat was my father. We came back to our apartment and all his stuff was gone.”

The trombone is a unique tool for bridge building. The producer of the album for which Mendoza won a Grammy was so happy to find a Dreamer with Mendoza’s skills on trombone that, Mendoza told the Recording Academy, he called the young man a “unicorn.”

Denzel Mendoza (left) performing with Haley Heynderickx (right) at the Portland stop of NPR's Tiny Desk Contest On the Road in 2017—click to see more photos by Tojo AndrianarivoMendoza’s bright horn grumble and singing is now key to Heynderickx’s sound, but he can’t join her for some shows. “I’ve had to turn down gigs in Iceland, many dates in Canada,” Mendoza says. “That’s a lot of money, among other things.”

Denzel Mendoza (left) performing with Haley Heynderickx (right) at the Portland stop of NPR's Tiny Desk Contest On the Road in 2017—click to see more photos by Tojo AndrianarivoMendoza’s bright horn grumble and singing is now key to Heynderickx’s sound, but he can’t join her for some shows. “I’ve had to turn down gigs in Iceland, many dates in Canada,” Mendoza says. “That’s a lot of money, among other things.”

Federal college loans don’t extend to undocumented immigrants, and Mendoza dropped out of NYC’s The New School for lack of funds. Then he briefly became what he calls his “mother’s worst nightmare”: homeless in New York. After a cousin graduated from West Point, Mendoza considered military service, but says when he spoke with a military recruiter, he was told he’s ineligible because he doesn’t speak a second language.

The ironies pile up: Mendoza is so American he only speaks English, not the Tagalog language of his Filipino roots. And a nation seemingly determined to keep out immigrants has a military that badly needs bilingual recruits.

“I was in between these giant towers of American or Filipino,” he recalls. “I was neither.”

A week later, a drummer friend drew him to Portland, and his trombone beckoned. Now, he holds forth on what he can do with music: “Destroy walls of hate.” As hardship becomes art, Illegal Son’s cacophony and motifs derive from “bitterness and sadness.”

Then he pauses, and laughs. “Wow, I sound like such an egotistical prick.”

Such humility is a leitmotif for Mendoza, Silva and myriad other immigrants, whose lives are often filled with toil—the proverbial “bootstraps” of our shared immigrant history. How many Grammy winners also work as landscapers, as Mendoza does?

The Turn Down

Portland immigrant artists say the feds are turning down the volume on their music, and careers. Dreamers—a common moniker for DACA recipients, derived from a bill liberals have long been trying to pass called the DREAM Act—are caught in limbo.

Edna Vázquez: Photo by Adolfo Cantú-Villarreal“It’s a loop,” says Heldáy de la Cruz, a graphic designer and Dreamer who heads Power to the Dreamers, which “aims to marry art and the undocumented narrative.” De la Cruz says he can’t stay and be whole, but neither can he easily go “home” to a country he hasn’t seen for 26 years, since age 2. “Even if I wanted to voluntarily deport, self-deport, which is something I’ve considered, it’s an entire process that a judge has to approve.”

Edna Vázquez: Photo by Adolfo Cantú-Villarreal“It’s a loop,” says Heldáy de la Cruz, a graphic designer and Dreamer who heads Power to the Dreamers, which “aims to marry art and the undocumented narrative.” De la Cruz says he can’t stay and be whole, but neither can he easily go “home” to a country he hasn’t seen for 26 years, since age 2. “Even if I wanted to voluntarily deport, self-deport, which is something I’ve considered, it’s an entire process that a judge has to approve.”

Edna Vázquez, a singer-songwriter from Mexico here on a U visa for victims of crime, is a legal permanent resident, but hasn’t been able to tour internationally as she waits for approval. “I’ve been waiting for these fucking papers since 2012,” Vázquez laments.

The waiting game is not new to Myers, the label head, who works with artists from Finland, Japan, Mexico, Canada, Norway and Turkey. “If the USCIS doesn’t like [an artist], instead of giving you a denial, they’ll give you a request for evidence,” Myers says. “This is what happened to Sebastian [Silva].”

Myers spends thousands—not including attorney’s fees—on each artist he sponsors. About half get approved, he says. Silva raised $3,500 via GoFundMe for his denied visa and is spending more for a new application round. Want to expedite an application? That’s another $1,410, please.

Denzel Mendoza: Illustration by Heldáy de la CruzArtists, labels and managers have to do tons of work to put together tours, knowing it could all be for naught. “[Officials] literally expect every detail of the tour or event to be booked and finalized before they give out said visas,” VanHoosen says. “So the agents and promoters have to do all the work before the band even knows if they can make it or not.”

Denzel Mendoza: Illustration by Heldáy de la CruzArtists, labels and managers have to do tons of work to put together tours, knowing it could all be for naught. “[Officials] literally expect every detail of the tour or event to be booked and finalized before they give out said visas,” VanHoosen says. “So the agents and promoters have to do all the work before the band even knows if they can make it or not.”

Anatomia, a Japanese metal band, was recently denied though they’ve toured here before and have a following, Myers says. Who gets through? Finntroll, a Finnish folk metal band, which Myers says draws 100,000 at some European festivals.

One band from Turkey, Myers notes, came to Portland on a tourist visa, a no-no, and a band member leaked they were here to perform. Imagine government officials interrogating a nervous Turkish musician—with no powerful Marshall stacks—in a windowless room at PDX. “I guess they grilled him so hard he got scared and told the truth and they deported him,” Myers says. The other band members “got on a random bus just to get out of the airport.”

The Homeland Security Wizards

Perhaps no American political issue has been as divisive as immigration. Since the Immigration Act of 1990, Congress has consistently failed to pass a comprehensive reform bill. In June, the Democratic-controlled House of Representatives passed the American Dream and Promise Act of 2019, but it’s unlikely to pass the Republican-controlled Senate.

Such deadlock has not slowed the growth of the immigration security bureaucracy.

Somewhere inside a fortress-like concrete edifice in a suburb south of Los Angeles, a USCIS wizard sits behind a curtain of paper and pixels, deciding whether or not to give Silva a visa. This highly educated adjudications officer is one of 229,000 employees of the Department of Homeland Security and receives about $100,000 per year to decide what “extraordinary ability” means.

It’s not clear whether they know anything about music.

USCIS spokeswoman Sharon Rummery says adjudications officers rule on applications from athletes, clergy, educators, business people and agricultural workers. The USCIS rules are complex and the process involves filing an I-129 petition for an O-1 visa. The federal government, she claims, doesn’t know the numbers of denials, only approvals. (There were 16,904 artist visa approvals last year.)

Illustration by Heldáy de la CruzAs a “matter of policy,” USCIS does not allow interviews with adjudications officers, Rummery says. Asked if adjudications officers are required to understand the arts, Rummery did not answer, instead noting they “attend training” and “research, interpret and apply appropriate statutes, regulations and precedent decisions.” Further questions about the role led her to email, “I’ve been told to suggest you file a Freedom of Information Act request.”

Illustration by Heldáy de la CruzAs a “matter of policy,” USCIS does not allow interviews with adjudications officers, Rummery says. Asked if adjudications officers are required to understand the arts, Rummery did not answer, instead noting they “attend training” and “research, interpret and apply appropriate statutes, regulations and precedent decisions.” Further questions about the role led her to email, “I’ve been told to suggest you file a Freedom of Information Act request.”

VanHoosen says USCIS uses “archaic” criteria for approval. A review of Silva’s denial paperwork mentions “box office receipts” and “trade journals,” but references to blogs, social media or streaming services are rare—and when mentioned, are deemed “insufficient” or unreliable.

Myers sees an arbitrary process. “It basically depends on who’s working that day and if they’re having a bad day or not,” he says.

Carlos Tovías, program director at Portland’s Mexican music radio station 93.1 El Rey, agrees federal visa rulings have “nothing to do with the quality or talent of the group.”

Major label backing doesn’t hurt, Tovías says. “A huge major label is better than an independent” for scoring a visa, he adds. “Universal or Capitol is better than Río Record Label that nobody knows.”

Silva’s papers reveal that USCIS prioritizes artists who “command a high salary or other substantial remuneration.” Such financial factors were likely a consideration when a Slovenian immigrant named Melanija Knavs began dating a billionaire named Donald Trump in 1998. Three years later the immigrant, now First Lady Melania Trump, obtained an “Einstein” visa for her “extraordinary ability” as a model.

Tovías says he doesn’t know the “problems [artists] are suffering.” He hears stories though, including about Mexican consulates. “One of the consulates, there’s a rumor that they have a little stage [inside], that you need to perform for them,” Tovías says.

The image is an immigration policy curio: a tiny stage somewhere near the U.S.-Mexico border, where mariachi and norteño musicians play their asses off to prove they’re not terrorists or narcotráficos.

María’s Charango

María Damaris says her charango is a weapon. Of love.

María Damaris plays her charango (left) while marching with Bajo Salario (including Leo Salazar, center with flute, and Paul Riek, right with the guitar-like jarana) at the Portland International Airport to protest the Muslim ban in January 2018: Photo by Douglas YarrowDamaris got the small, 10-stringed Andean instrument in 2005 from a roommate in lieu of rent. She says she’s used its distinctive sound to lead marches, free people from Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detention, and win over judges.

María Damaris plays her charango (left) while marching with Bajo Salario (including Leo Salazar, center with flute, and Paul Riek, right with the guitar-like jarana) at the Portland International Airport to protest the Muslim ban in January 2018: Photo by Douglas YarrowDamaris got the small, 10-stringed Andean instrument in 2005 from a roommate in lieu of rent. She says she’s used its distinctive sound to lead marches, free people from Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detention, and win over judges.

Damaris is part of Bajo Salario (translation: Crappy Wages), a collective she estimates has played 400 gigs over the years, including at Occupy ICE, the Latinos Unidos Siempre march and the women’s marches. In an accent that still carries a trace of Morelia, Mexico, she recounts an interaction with an official at Portland’s ICE offices she says led to the release of an immigrant facing deportation.

“I went to immigration and told them, ‘I have this charango, and we’re going to be playing to say goodbye to him.’ They were like, ‘Wait, no. You cannot bring your charango, and you cannot play your musical instruments.’

“I was like, ‘Well, okay then, we will be playing out in the streets where you have no jurisdiction.’

“They come back and say, ‘We will release him in an hour or two—just go.’

“We said, ‘Well, we are not in a rush.’” Damaris says jarocho or fandango can be more powerful than words.

Damaris and her charango (center) with Bajo Salario“I am a very confrontational person. I have that fire in my heart, very passionate. But when we play music, we are very different. We are the loving people where we don’t need to use our words in anger.”

Damaris and her charango (center) with Bajo Salario“I am a very confrontational person. I have that fire in my heart, very passionate. But when we play music, we are very different. We are the loving people where we don’t need to use our words in anger.”

While young people may conflate today’s immigration battles with President Trump’s hateful rhetoric, Damaris sees a continuum that includes Democrats and leftist politicians. “The person who wanted to deport my husband was not Donald Trump, it was Obama,” she says. “This has been happening forever.”

Damaris says Bajo Salario was invited to play onstage with Bernie Sanders in 2016, but had to turn it down because the collective would not acquiesce to FBI background checks. “It was like my dream,” Damaris says, “because most of us are legally here, and we wanted to be on that stage supporting Bernie Sanders.”

Not even jamming with Bernie is worth risking deportation.

Wade in the Water

Water is among the powerful themes in 21 Cartas, a collaboration between jazz pianist-composer Darrell Grant, pan-Latin troubadour Edna Vázquez and filmmaker Adolfo Cantú-Villarreal. The work is sourced from letters Cameron Madill collected from undocumented mothers incarcerated in a for-profit, refugee prison in South Texas. Written in 2016 while President Obama was in office, the 21 letters are a study in the power of heartache, exploring “what it means to be a mother in prison on Mother’s Day.”

21 Cartas connects the suffering of undocumented immigrants with slavery, weaving together Latin American folclórico and African American spirituals.

“Who’s that angel dressed in white?” Grant sang in a low, sonorous voice over buttery organ chords at the May 10 debut of 21 Cartas at the Alberta Rose Theatre. “Wade in the water / One more child of the Israelites / God’s gonna trouble the water.”

Darrell Grant and Edna Vázquez at the premiere performance of '21 Cartas' at the Alberta Rose Theatre on Mother’s Day weekend—click to see more photos by Miri StebivkaThe Red Sea has become the Rio Grande. Water, the tool of baptism, separates life and death in the vast deserts of northwest Mexico and the southwestern U.S. Behind the two musicians, clad in white, Cantú-Villarreal’s haunting video and imagery surveyed the La Bestia trains and broad rivers. During a poignant moment, both musicians’ heads bowed.

Darrell Grant and Edna Vázquez at the premiere performance of '21 Cartas' at the Alberta Rose Theatre on Mother’s Day weekend—click to see more photos by Miri StebivkaThe Red Sea has become the Rio Grande. Water, the tool of baptism, separates life and death in the vast deserts of northwest Mexico and the southwestern U.S. Behind the two musicians, clad in white, Cantú-Villarreal’s haunting video and imagery surveyed the La Bestia trains and broad rivers. During a poignant moment, both musicians’ heads bowed.

Water is both barrier and bridge, Vázquez says. “What I understand is something like, ‘God’s gonna trouble the water,’ because if it weren’t so, then how could we advance as human beings?”

After the show, an old woman approached Vázquez. “Que dios la bendiga,” she said. “God bless you.”

“That was very powerful,” Vázquez says. “Because what I understood from her was, ‘Thank you for being brave enough to talk about this,’ and ‘God bless you’ because you’re risking your life.”

Hyperbole? Maybe not. A recent New York Times article seems to confirm the worst fears of many, detailing federal steps towards using information obtained through public benefits like housing vouchers and food stamps to start deporting people.

A day before that show, a Power to the Dreamers event featured de la Cruz’s art and “raw” interviews between four parents and their Dreamer children, including Mendoza.

A common thread was the sacrifice emigrating entails, de la Cruz recalls. “It wasn’t even a choice, [emigration] was something that needed to happen for them to get along, to survive, to be able to provide a future for their children.”

He quotes from a poem by Somali-British writer Warsan Shire:

you have to understand,

that no one puts their children in a boat

unless the water is safer than the land

no one burns their palms

under trains

beneath carriages

no one spends days and nights in the stomach of a truck

feeding on newspaper unless the miles travelled

means something more than journey.

Music, and art, in the end, is a way to overcome fear, and trauma—not just for immigrant artists, but for all of us. No border wall can separate that which magnetizes ears and eyes.

“I would like to motivate people to look each other in the eyes, and not be afraid,” Vázquez says. Her words recall a move Heynderickx and Mendoza made during their NPR Tiny Desk Concert when they proffered “five seconds of intimate eye contact to the camera, to show the people we love back home that we love them.”

“Let’s be more aware of our humanity,” Vázquez says, “to be able to advance more.”