Chris Shiflett (left) with Foo Fighters during their last Portland appearance at the Moda Center in September 2015—click to see a whole gallery of photos by John AlcalaAt the outset, Chris Shiflett appears far from the archetypal alt-country frontman. A shaggy-haired, punk rock veteran and surf aficionado hailing from Santa Barbara, Shiflett is undoubtedly best known from his 20-year tenure with the Foo Fighters—a band whose recent work has increasingly channeled the rootsy thrust of classic American music, but nevertheless remains worlds apart from the stylism of Sturgill Simpson, Chris Stapleton and Jason Isbell, Nashville’s contemporary vanguard.

Chris Shiflett (left) with Foo Fighters during their last Portland appearance at the Moda Center in September 2015—click to see a whole gallery of photos by John AlcalaAt the outset, Chris Shiflett appears far from the archetypal alt-country frontman. A shaggy-haired, punk rock veteran and surf aficionado hailing from Santa Barbara, Shiflett is undoubtedly best known from his 20-year tenure with the Foo Fighters—a band whose recent work has increasingly channeled the rootsy thrust of classic American music, but nevertheless remains worlds apart from the stylism of Sturgill Simpson, Chris Stapleton and Jason Isbell, Nashville’s contemporary vanguard.

Appearances, however, can be deceiving. Home to the “Bakersfield sound,” which was brought to the region by a wave of Dust Bowl migrants and popularized by Merle Haggard and Buck Owens, California, in fact, features prominently along the historical continuum of country music. Shiflett has spent periods of downtime from Foo Fighters exploring the genre’s various facets through Walking The Floor, a popular podcast featuring over 70 hour-plus interviews with country’s elite, including Haggard, Simpson and Margo Price, as well a piquant cast of personalities from surf filmmaking legend Jack McCoy to Freddie Roach, the boxing guru who has trained the likes of Manny Pacquiao and Oscar De La Hoya.

In fact, an interview with Dave Cobb on Walking The Floor would lead to the recording of West Coast Town, Shiflett’s latest solo effort, which is set to be released on April 14. Upon the conclusion of their conversation, held shortly after Cobb took up residency at Nashville’s storied RCA Studio A, Shiflett was determined to record with the white-hot producer, who has applied his gilded touch to a royal flush of albums including Sturgill Simpson’s Metamodern Sounds in Country Music, Chris Stapleton’s Grammy-winning Traveller, and Southeastern, Jason Isbell’s peerless breakthrough effort.

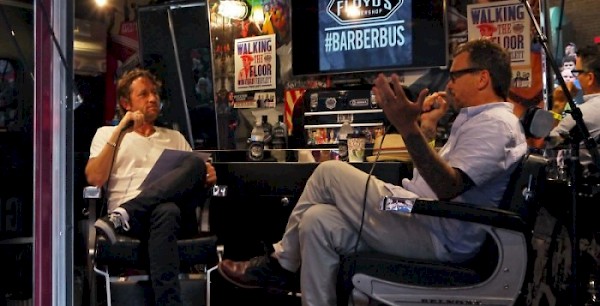

Shiflett interviews Dicky Barrett of The Mighty Mighty Bosstones for 'Walking The Floor'It follows that, with Cobb at the helm, the breezy, live-tracked feel and broad coherence of West Coast Town is of little surprise. Bolstered by the accompaniment of Cobb’s longtime session hands, Shiflett’s compositions showcase a burgeoning knack for quality pop songwriting that finds a deft balance between country and punk rock traditions that, in less capable hands, may otherwise seem forced or irreconcilable. While the album gradually loses momentum over the duration of its 10 tracks, leadoff cut “Sticks and Stones” has all the formidable instrumental muscle and staying power of a proper single, making for a fulfilling listen and a strong case for a prompt follow-up.

Shiflett interviews Dicky Barrett of The Mighty Mighty Bosstones for 'Walking The Floor'It follows that, with Cobb at the helm, the breezy, live-tracked feel and broad coherence of West Coast Town is of little surprise. Bolstered by the accompaniment of Cobb’s longtime session hands, Shiflett’s compositions showcase a burgeoning knack for quality pop songwriting that finds a deft balance between country and punk rock traditions that, in less capable hands, may otherwise seem forced or irreconcilable. While the album gradually loses momentum over the duration of its 10 tracks, leadoff cut “Sticks and Stones” has all the formidable instrumental muscle and staying power of a proper single, making for a fulfilling listen and a strong case for a prompt follow-up.

Chris Shiflett will be performing songs from West Coast Town on Tuesday, March 21 at Portland’s Hawthorne Theatre. Preceding this appearance, Music Millennium will host Shiflett for a short acoustic set and signing.

Can you walk me through your background in music independent of your work with the Foo Fighters? West Coast Town has this cool country-punk dichotomy, which sounds surprisingly natural, and it made me interested in hearing you speak to your own identity as a musician.

I was lucky—I had two older brothers who had great record collections, and for most of my childhood I just listened to whatever they had. That was the '70s and the '80s, so it was a lot of what you would expect: just classic rock, like The Stones, The Beatles, Zeppelin, Aerosmith... that kind of thing.

As the years went on, we got super into heavy metal and shredding guitar heroes and all that sort of stuff. I got really into a band called Hanoi Rocks, and that was a huge turning point for me, musically. It also sort of coincided with this back-to-basics rock and roll thing that was happening. So, my early shows were like Dio and Armored Saint, and shit like that. I went to a lot of those kinds of gigs when I was in junior high. And then I started going to see bands down in L.A., like Poison and Jetboy and Faster Pussycat and L.A. Guns. I got to see all of those bands in the clubs way back when. That was my world. [Laughs]

No kidding. I’d have never guessed.

But growing up in Santa Barbara, it wasn’t like there was a glam rock scene or a rock and roll scene where we were. It was just me and a couple of friends. So, in terms of access, if you were going to go see a band on weekends, it was always at a keg party somewhere in Isla Vista and it was a punk rock band or it was a speed metal band. There was a lot of that in the '80s—lots of punk rock and lots of thrash metal. That was also when I first started getting turned on to punk rock. One of the first gigs I ever played was when I was in a band called Legion of Doom. We opened up for Rat Pack, Excel and NOFX at this pool hall down on State Street. And you don’t realize how life changing those things are when they happen, but that was my first time ever seeing NOFX. And they were fucking horrible in those days. [Laughs]

So, anyway, life goes on and music changes and things happen. I had a band before Foo Fighters called No Use For A Name, and the singer was this guy named Tony Sly. He was really into the country stuff that was going on, and turned me on to Uncle Tupelo, the first Son Volt record, and Whiskeytown—all those bands that were kicking off in the mid-'90s. That was kind of my entry point.

But I was such a massive Stones fan growing up. That music really just spoke to me. I think that, in terms of influences, I didn’t get into country music until I was a little older. But there were certainly influences I didn’t realize I was soaking up, you know? Listening to Sticky Fingers and Exile On Main St. and all that stuff that had some of that influence in it was maybe why alt-country stuff appealed to me so much; just because a lot of it was super Stones-y. And once I went down into that, it was just a couple steps to Merle Haggard. Little by little, you just get more and more into certain things, and you just sort of follow them down.

Did you ever look to folk music?

To this day, I can’t honestly say I’ve never gone through a folk phase. [Laughs] It’s probably something where I should go and dig out some old records and figure it out. But I was a really late convert to Bob Dylan, as ridiculous as it sounds. When I was growing up, man, I was into Judas Priest and shit like that. Bob Dylan just didn’t register with me. I remember seriously thinking to myself, “Why does everybody think that guy’s such a big deal?” [Laughs] Which seems so silly now, you know? It’s like, now that you’re a little older and you can get it. But that stuff just didn’t appeal to me at all when I was a kid, so I dove into it later.

But from a songwriting point of view, it’s interesting: I kind of started writing songs late. I was in bands where there was always another songwriter. There was always a primary songwriter in every band I was in, even in high school. So I really never explored that. I don’t think I had the confidence, really. I always had little ideas; little lyrical ideas and riffs and things like that. But I started writing more in my 20s, and then in my 30s I did it a lot. I had a band called Jackson United, and did a couple records with them, and then did a couple Dead Peasants records, and then this one.

Shiflett with the Dead PeasantsIs songwriting something you feel comes pretty naturally to you now? Or can it be something of a struggle?

Shiflett with the Dead PeasantsIs songwriting something you feel comes pretty naturally to you now? Or can it be something of a struggle?

Well, I don’t think of it as a struggle, but I’m much more comfortable with it. And I’m much more comfortable just singing and stuff. It’s kind of hard to get over that hump, just being like, “My voice is my voice, and that’s what it is.” [Laughs]

Right.

Because you’re pretty exposed. I mean, I’ve been doing a lot of just acoustic gigs leading up to this tour. And that can be so awkward, I figured that, if I can get comfortable doing that, by the time I went out and did it with a band, I’d be really comfortable.

Can you talk about how Dave Cobb got involved with West Coast Town? I’m not sure there’s a better producer out there right now.

You know, I was just a big, huge fan of his work, and I reached out and cold-called him once to see if I could interview him for my podcast. I was going to be out in Nashville doing some interviews, and he said that I could. So, I went and interviewed him the week he took over RCA Studio A, where we recorded my record, and that’s where we did the interview—we were just out there in the room. He was just such a cool guy and I just love his work. After I interviewed him, I thought, “Wow, the next time I make a record, I’ve got to make a record with that guy.” I called him a couple months later, and asked him if he would do it. He agreed and he had some open time in the summer, and that was that!

It was a little daunting going out there because I didn’t really know him and hadn’t worked with him, and I didn’t know any of the people who were going to be playing on the record. I didn’t go out there with a band; it was just me, a couple guitars and a notebook full of songs. But once we got through the first couple of songs, I relaxed and was like, “Ah, this is going to be great.”

In past interviews—including the one you guys did on Walking The Floor—I recall Jason Isbell saying that Cobb is adept at toeing the line between serving that crucial editorial function—saying that certain things do or do not work, and bringing in ideas—while remaining a constructive and generally positive presence. Was that true in your experience?

Yes—absolutely. He really had a massive impact on my songs in terms of arrangement, adding sections here and there. There were a couple songs where he said, “You need to add a bridge to that one,” or whatever. He was just an endless source of ideas in that way. You know, “You’ve got to drop those lyrics,” or, “You need a better tag for that.” But he keeps it moving, and he keeps it fun and really relaxed. It’s never like you’re too stressed or working too hard. We made the whole thing—recorded, mixed and finished it—in about three weeks. So you get a lot done pretty quickly.

What led you to him, and to that contemporary Nashville scene, in the first place?

Well, I must’ve heard some Shooter Jennings stuff that he had done—and that I didn’t realize he had done—and Jamey Johnson. I didn’t know that he had done some of the Jamey Johnson stuff that I liked. But I guess the one that first led me to really register who he was and what he was doing was that second Sturgill Simpson record.

That was Metamodern Sounds In Country Music, right?

Yes—yeah. I think that was probably the one. So, it was the Sturgill Simpson stuff, the Isbell stuff, the Chris Stapleton record [Traveller]. He’s made a lot of really cool records that sound amazing.

Have other producers you’ve worked with, like Nick Raskulinecz and Butch Vig, had that same vibe about them? Is it something of a hallmark of a good producer?

Yeah, I think that great producers keep the engine moving forward—especially with a whole band situation. I mean, for my record, it wasn’t a band situation. Once we got all the basic tracks with the rhythm section, it was mostly just me and Dave and Matt [Ross-Spang], who engineered it. Then different people would come in and overdub some steel and some keys, and some stuff like that.

But in a band situation, when you’ve got all these different people and all these different opinions—and a slightly different take—producers keep it organized and moving along. Because you can really lose sight of a record in the middle of making it.

Right. And that can be dangerous when studio time is so expensive.

Yeah, sure. [Laughs]. You know, the cool thing about the last couple Foo Fighters records we’ve done, is that we do them a song at a time, which is a different way of doing it. But if you have the means, that’s the best way to do it.

Who did you guys bring in to play on the album?

It’s Chris Powell on drums and Adam Gardner on bass. Dave Cobb is playing acoustic guitar, and I’m on electric. The basic tracks were done live with no click—that’s how we tracked everything. Once we got that, then I added more guitars. Then we got Robby Turner to come in and play pedal steel.

The pedal steel accompaniment on “Sticks and Stones” was really well done.

Yeah, dude. He’s amazing, absolutely incredible. Kristen Rogers sang all the harmonies, Michael Webb played all the keys, and I think that’s everybody.

Just out of curiosity, who are the A-list pedal steel players in Nashville right now? I know that Paul Franklin and Al Perkins get a lot of work. But I’d imagine there are a number of others out there.

Yeah, Paul Franklin is one of the super famous ones. The other I guy I know of is Bruce Bouton, who plays with Garth Brooks and still lives in Nashville. He’s amazing. But, you know, I’m not really sure. There are certainly far more guys out there doing it than on the West Coast.

I’m sure they’re not hurting for gigs, either.

A good pedal steel player, I’d imagine, writes his own ticket. [Laughs]

I’ve been really enjoying your podcast as well, and wanted ask how you arrange it so that it doesn’t conflict with everything else you’ve got going on? Do you have a space that people drop by? Or will you coordinate interviews depending on where you are at a given point in time?

It depends. I have a little studio here in L.A., and if people are passing through I try to get them to come there because I have my little setup. But really, all you need is a place that’s quiet. I’ve even done interviews that weren’t quiet at all, and you can hear some noise in the background. [Laughs] But, ideally, you get somewhere that’s quiet, and if you just take a laptop and a couple mics, you can do it anywhere.

It is definitely harder to coordinate when I’m working a lot, and might end up missing some great interview opportunities. But during the first half of last year, I wasn’t doing a whole lot, so I did a million interviews in a pretty short amount of time. I did as many as I could do, and I just banked them. And it’s funny, I got so backlogged during that time, that I’m actually posting the last one of those interviews—I think I did it a year ago. It’s with Bob Mould [Hüsker Dü, Sugar], and I’m posting it on Monday. I completely cleared out the archive!

Shiflett with Foo FightersIn interviews, I’ve heard Dave Grohl talk about how the Foo Fighters have the luxury of operating in something of a bubble and on their own time. Has your experience with smaller-scale records like West Coast Town given you a different perspective on what it’s like out there for bands trying to come up and make a name for themselves?

Shiflett with Foo FightersIn interviews, I’ve heard Dave Grohl talk about how the Foo Fighters have the luxury of operating in something of a bubble and on their own time. Has your experience with smaller-scale records like West Coast Town given you a different perspective on what it’s like out there for bands trying to come up and make a name for themselves?

Yeah. I think it is so radically different than it was when I was 20-something and first getting in a van and going on tour and making records. I’ve always done small tours and small records all through the years I’ve been in the Foo Fighters, so it’s never really been something that I’ve gotten out of touch with, you know?

But, honestly, I interviewed a guy yesterday named Sam Outlaw, who’s an up-and-comer, and I was asking him, “How the fuck do you do it? How do you put a band together, rent a van, go on the road together and book hotel rooms?” It doesn’t add up.

Right. That’s what it seems like.

Honestly, in this day and age, where record labels don’t really offer tour support and stuff, I don’t know how they do it. I mean, I know how I do it—it’s not a money maker for me. It’s something I lose money doing, but I just enjoy it. I do it fucking bare bones, you know? And it still loses me a shitload of money. [Laughs] So it’s a bit of a mystery to me. But I think part of it is, you have to be 25 years old and just say, “Fuck it. I don’t care where I sleep tonight. I’m going to go.”

And I understand that spirit. You just have to be in that state of mind to do it.